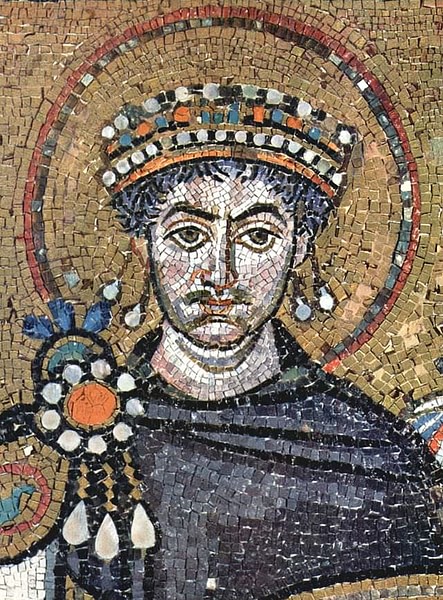

During the reign of the emperor Justinian I (527-565 CE), one of the worst outbreaks of the plague took place, claiming the lives of millions of people. The plague arrived in Constantinople in 542 CE, almost a year after the disease first made its appearance in the outer provinces of the empire. The outbreak continued to sweep throughout the Mediterranean world for another 225 years, finally disappearing in 750 CE.

Plague Origination & Transmission

Originating in China and northeast India, the plague (Yersinia pestis) was carried to the Great Lakes region of Africa via overland and sea trade routes. The point of origin for Justinian's plague was Egypt. The Byzantine historian Procopius of Caesarea (500-565 CE) identified the beginning of the plague in Pelusium on the Nile River's northern and eastern shores. According to Wendy Orent, author of Plague, the disease spread in two directions: north to Alexandria and east to Palestine.

The means of transmission of the plague was the black rat (Rattus rattus), which traveled on the grain ships and carts sent to Constantinople as tribute. North Africa, in the 8th century CE, was the primary source of grain for the empire, along with a number of different commodities including paper, oil, ivory, and slaves. Stored in vast warehouses, the grain provided a perfect breeding ground for the fleas and rats, crucial to the transmission of plague. William Rosen, in Justinian's Flea, contends that while rats are known to eat just about anything (including vegetable matter and small animals), grain is their favorite meal. Rosen further observes that rats generally do not travel more than 200 meters from their birthplaces over the course of their lifetimes. However, once aboard the grain boats and carts, the rats were carried throughout the empire.

According to historian Colin Barras, Procopius recorded the climatic changes taking place in southern Italy during the period: unusual incidents of snow and frost in the midst of summer; below average temperatures; and a decrease of sunshine. So began a decades-long cold snap accompanied by social disruptions, war, and the first recorded outbreak of the plague. The colder than usual weather affected crop harvests, leading to food shortages that resulted in the movements of people throughout the region. Accompanying these reluctant migrants were plague-infected, flea-ridden rats. Cold, tired, hungry people on the go, combined with illness and disease in the midst of warfare, as well as an increased rat population carrying a highly infectious disease, created the perfect conditions for an epidemic. And what an epidemic it would be: named after the Byzantine emperor Justinian I (482-565 CE; emperorship 527-565 CE), Justinian's plague affected nearly half the population of Europe.

TYPES OF PLAGUE & SYMPTOMS

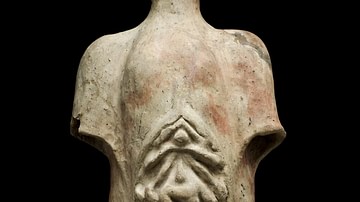

Based upon DNA analysis of bones found in graves, the type of plague that struck the Byzantine Empire during the reign of Justinian was bubonic (Yersinia pestis), although it was very probable that the other two types of plague, pneumonic and septicemic, were also present. It was also bubonic plague which would devastate 14th-century CE Europe (better known as the Black Death), killing upwards of 50 million people or nearly half the entire population of the continent. Plague was not new to history even in the time of Justinian. Wendy Orent suggests that the first recorded account of bubonic plague is told in the Old Testament in the story of the Philistines who stole the Ark of the Covenant from the Israelites and succumbed to “swellings.”

Procopius, in his Secret History, describes victims as suffering from delusions, nightmares, fevers and swellings in the groin, armpits, and behind their ears. Procopius recounts that, while some sufferers lapsed into comas, others became highly delusional. Many victims suffered for days before death, while others died almost immediately after the onset of symptoms. Procopius' description of the disease almost certainly confirms the presence of bubonic plague as the main culprit of the outbreak. He laid blame for the outbreak on the emperor, declaring Justinian to be either a devil or that the emperor was being punished by God for his evil ways.

The Spread of the Plague through the Byzantine Empire

War and trade facilitated the spread of the disease throughout the Byzantine Empire. Justinian spent the early years of his reign defeating a variety of enemies: battling Ostrogoths for control over Italy; fighting Vandals and Berbers for control in North Africa; and fending off Franks, Slavs, Avars, and other barbarian tribes engaged in raids against the empire. Historians have suggested that soldiers, and the supply trains supporting their military efforts, acted as the means of transmission for the rats and fleas carrying the plague. By 542 CE, Justinian had re-conquered most of his empire but, as Wendy Orent points out, peace, prosperity, and commerce also provided appropriate conditions for facilitating a plague outbreak. Constantinople, the political capital of the eastern Roman Empire, doubled as the center of commercial trade for the empire. The capital's location along the Black and Aegean seas made it the perfect crossroads for trade routes from China, the Middle East, and North Africa. Where trade and commerce went, so went rats, fleas, and the plague.

Wendy Orent chronicles the course of the disease. Following the established trade routes of the empire, the plague moved from Ethiopia to Egypt and then throughout the Mediterranean region. The disease penetrated neither northern Europe nor the countryside, suggesting the black rat was the primary carrier of the infected flea as the rats kept close to the ports and ships. The outbreak lasted about four months in Constantinople but would continue to persist for roughly the next three centuries, with the last outbreak reported in 750 CE. There would be no more large-scale outbreaks of plague until the 14th century CE Black Death episode.

The plague was so widespread that no one was safe; even the emperor caught the disease, though he did not die. Dead bodies littered the streets of the capital. Justinian ordered troops to assist in the disposal of the dead. Once the graveyards and tombs were filled, burial pits and trenches were dug to handle the overflow. Bodies were disposed of in buildings, dumped into the sea, and placed on boats for burials at sea. And it was not just humans who were affected: animals of all types, including cats and dogs, perished and required proper disposal.

Plague Treatment

Once affected, people had two courses of action: treatment by medical personnel or home remedies. William Rosen identifies the medical personnel as primarily trained physicians. Many of the physicians engaged in a four-year course of study taught by trained practitioners (iastrophists) at Alexandria, then the premier center for medical training. The education received by the students primarily centered on the teachings of the Greek physician Galen (129-217 CE), who was influenced in his understanding of disease by the concept of humorism, a medical system which relied on the treatment of disease based upon bodily fluids, known as "humors".

Lacking access to one of the types of physicians—court, public, private—people often turned to home remedies. Rosen identifies various approaches people took towards treating the plague including cold-water baths, powders “blessed” by saints, magic amulets & rings, and various drugs, especially alkaloids. Failing all the previous approaches to treatment, people turned to hospitals or found themselves subject to quarantining. Those who did survive were credited, according to Rosen, with “good fortune, strong underlying health and an uncompromised immune system”.

Effects on the Byzantine Empire

The plague episode contributed to a weakening of the Byzantine Empire in political and economic ways. As the disease spread throughout the Mediterranean world, the empire's ability to resist its enemies weakened. By 568 CE, the Lombards successfully invaded northern Italy and defeated the small Byzantine garrison, leading to the fracturing of the Italian peninsula, which remained divided and split until re-unification in the 19th century CE. In the Roman provinces of North Africa and the Near East, the empire was unable to stem the encroachment of Arabs. The decreased size, and the inability of the Byzantine army to resist outside forces, was largely due to its inability to recruit and train new volunteers due to the spread of illness and death. The decrease in the population not only impacted the military and the empire's defenses, but the economic and administrative structures of the empire began to collapse or disappear.

Trade throughout the empire became disrupted. In particular, the agricultural sector was devastated. Less people meant fewer farmers who produced less grain causing prices to soar and tax revenues to decline. The near collapse of the economic system did not dissuade Justinian from demanding the same level of taxes from his decimated population. In his determination to recreate the former might of the Roman Empire, the emperor continued to wage wars against the Goths in Italy and the Vandals at Carthage lest his empire disintegrate. The emperor also remained committed to a series of public work and church construction projects in the capital including the building of the Hagia Sophia.

Procopius reported in his Secret History of nearly 10,000 deaths per day afflicting Constantinople. His accuracy has been questioned by modern historians who estimate 5,000 deaths per day in the capital city. Nonetheless, 20-40% of the inhabitants of Constantinople would eventually perish from the disease. Throughout the rest of the empire, nearly 25% of the population died with estimates ranging from 25-50 million people in total.