In 1845 CE, the archaeologist Austen Henry Layard began excavations at the ruins of the city of Nimrud in the region which is northern Iraq in the present day. Layard's expedition was part of a larger movement at the time to uncover ancient sites in Mesopotamia, which would corroborate stories found in the Bible, specifically in books in the Old Testament such as Genesis and Jonah. The archaeologists who excavated the sites throughout Mesopotamia in the mid-19th century CE were seeking physical evidence to support accounts of the Great Flood, the Tower of Babel, and cities such as Nineveh and Calah, among other biblical references. Their work, ironically, would have the complete opposite effect of what was intended: they discovered a civilization that existed long before the first biblical books were written, one which had, in fact, produced the first stories concerning a global flood and an ark, and which was far more advanced than had previously been thought. These discoveries would revolutionize human understanding of world history which, previously, had been heavily influenced by the Bible's version of events. Prior to these expeditions, little was known about Mesopotamian history outside of the Assyrians and Babylonians because they were the people best documented by the Greek historians and mentioned in the Bible. The great Mesopotamian cities of the past lay buried under the sands after the fall of the Assyrian Empire in 612 BCE, and their histories lay buried with them.

History of the City and Discovery of the Ivories

When Layard began his work at Nimrud, he did not even know which city he was excavating. He believed he had discovered Nineveh and, in fact, published his best-selling book on the excavation, Nineveh and its Remains, in 1849 CE, still confident in that belief. His book was so popular, and the artifacts he uncovered so intriguing, that further expeditions to the region were quickly funded. Further work in the region established that the ruins Layard had uncovered were not those of Nineveh but of another city, which was then referred to as Nimrud. The archaeologist William K. Loftus took over from Layard in 1854 CE and excavated Nimrud further discovering, among other treasures, the magnificent works of art known today as the Nimrud Ivories (also as the Loftus Ivories). Nimrud was an important city in ancient Mesopotamia known as Kalhu (also Caleh, Calah), which became the capital of the Assyrian Empire under Ashurnasirpal II (reigned 884-859 BCE), who moved the central government there from the traditional capital of Ashur.

The city existed as an important trade center from at least the 1st millennium BCE. It was located directly on a prosperous route just north of Ashur and south of Nineveh. The Assyrian Empire was ruled from Kalhu from 879-706 BCE, when Sargon II (reigned 722-705 BCE) moved the capital to his new city of Dur-Sharrukin (Khorsabad). Following the death of Sargon II, his son Sennacherib (reigned 705-681 BCE) abandoned Dur-Sharrukin and moved the capital to Nineveh. Kalhu continued to be an important city to the Assyrians, however, and the palaces and residences were richly adorned and ornamented with gold, silver, precious gems, and the intricate works of art that have come to be known as the Nimrud Ivories.

The Importance of the Nimrud Ivories

Historian and curator Joan Lines of the Metropolitan Museum of Art describes these pieces:

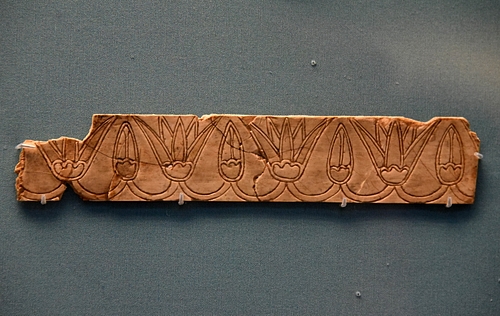

The most striking objects from Nimrud are the ivories - exquisitely carved heads that once must have ornamented furniture in the royal palaces; boxes inlaid with gold and decorated with processions of small figures; decorative plaques; delicately carved small animals (234).

Layard's expedition had uncovered the first of the ivories, while Loftus discovered many more. While Loftus was working at Nimrud, the city of Nineveh was positively identified and international attention, and funding, went toward that excavation as well as work on the recently discovered city of Khorasbad. Nimrud was neglected until 1949 CE, when archaeologist Max E. Mallowan of the University of London (husband of the mystery writer Agatha Christie) began excavations there, which lasted until 1963 CE. Mallowan uncovered the largest number of ivories in the structure known as the North West Palace (also called the Burnt Palace). These included some of the most famous pieces on display in the world today, such as the "Mona Lisa" head, which was found in a well in the palace. Historian Chris Allen describes the uses of these ivories by the Assyrians as well as their origin:

Most ivories formed decoration on parts of furniture such as chairs, tables, possibly beds, or on boxes. They were also decorated with gold which has been stripped off. Ivory was readily accessible from the herds of elephants which were hunted in Syria up to the Ninth Century when they became extinct. Ivory tusks were also taken as tribute in war. Most ivories were received [in Nimrud] already carved, as booty or as gifts (3).

When the Assyrian Empire fell in 612 BCE, Kalhu and the other great cities were sacked by the armies of the Babylonians, Medes, and Persians. The palaces were burned after anything of value was taken from them. Apparently, the gold was stripped from the ivories at this time, and the ivory pieces themselves discarded or thrown down the palace well as worthless to the invaders. This seems somewhat strange at first since, as Joan Lines, notes, ivory had a long history in the region as a valuable commodity:

Ivory, as we know both from excavation and from historical records, was highly prized and in extensive use at the time of the Assyrian empire. The classical Biblical reference is, of course, Ahab's house of ivory at Samaria, where modern excavations revealed ivories related to those from Nimrud. Contemporary inscriptions provide many records of ivories sent as tribute to the Assyrian kings and of the use of ivory by them. We read of Assurnasirpal taking "couches of ivory overlaid with gold" from a city on the western Tigris and receiving tribute of "elephant tusks and ivory thrones overlaid with gold and silver." "All Phoenicia" sent gifts, including ivory and elephants to him. In the inventory of loot taken from Damascus by Adad Nirari III are listed beds and stools of ivory from the royal palace. Sargon II is said to have had a palace of ivory, and included in the tribute paid by Hezekiah of Judah to Sennacherib in 701 B.C. were couches of ivory and the tusks and hides of elephants (235).

It is likely that, since the ivory ornamentation would have been associated with the hated empire the invaders were overthrowing, they discarded the ivories as symbols of that empire after stripping them of their gold. By throwing the ivories down the well of the palace, the invaders inadvertently helped to preserve them, as the mud of the well sealed the pieces and kept them perfectly intact. More ivories were discovered by Mallowan in an arsenal in the palace where, it seems, they were stored as booty and either overlooked by the invaders of 612 BCE or simply ignored. These were also well preserved by the invading forces, since the walls and roof of the burning palace buried and protected them.

The Different Styles of the Ivories

When they were discovered, they were at first cleaned using Agatha Christie's face cream. An article in the Daily Mail from 2011 cites a passage from Christie's 1977 autobiography in which she wrote how "I had my own favourite tools; an orange stick, a very fine knitting needle... and a jar of cosmetic face cream for gently coaxing the dirt out of the crevices" (1). Once the ivories were cleaned, the kind of detail and craft apparent in the work amazed Mallowan and his crew. As Lines writes, "The work of the ivory-carvers was supreme among that of ancient craftsmen" (235). More ivories were discovered at Nimrud in a private house, and these were found to be older than the others and are thought to have been kept as heirlooms. The precision of the craftsmanship and the beauty of the ivories would have certainly made them prized possessions of any family.

As the ivories were cleaned, sorted, and further examined, it became apparent that they were of different styles and from different points of origin. Chris Allen explains these differences, citing the original work of Max Mallowan:

The Nimrud ivories have been identified as representing three separate styles: Assyrian, Phoenician, and Syrian. The Assyrian style is mainly characterized by its technique, that is, the images are incised by a sharp instrument on a flat ivory surface. They also have a particular content, that is, with subjects also found on the relief sculptures [of the palace at Nimrud]: war scenes, processions, and protective gods, etc...The Phoenician style is distinctive through its use of Egyptian imagery including gods, sundiscs, mythical animals, even hieroglyphs, although the latter are usually meaningless...Finally the Syrian style is arguably more artistic and three-dimensional, or sculptural, in its imagery. Many of these are heads and full length figures of women which may have been handles for other artefacts, and they include the `Mona Lisa'. Carved bulls and calves used on box lids are also in this style...The Phoenician style is attributed to the city states along the Mediterranean coast; and those in the Syrian style broken down by subject matter into particular cities across Syria. [The Assyrian style was created] at Nimrud by craftsmen from elsewhere (3-5).

The Phoenician ivories are the oldest and lay the foundation of technique which was used by later craftsmen. Joan Lines explains that, "the Phoenicians furnished not only ivory but also the technique of working it, which they had probably learned from the Egyptians, the first people in the ancient world to use it to any great extent. Phoenician ivories, showing strong Egyptian influence, are the earliest of those found in the Near East, and in that region the Phoenicians remained for centuries the most skillful ivory-carvers" (235). The techniques of the Phoenicians were then developed by others, such as the Syrians, into the three-dimensional imagery referred to above by Allen but the Phoenician style is still generally considered the most skillful.

Further Excavations at Nimrud & the Ivories Today

In 1988-1989 CE the Iraq Offices of Antiquity and Heritage again excavated at Nimrud and uncovered further treasures and valuable discoveries such as the tomb of Queen Yaba, wife of Tiglath-Pileser III and that of Queen Atalia, wife of Sargon II, along with great quantities of gold and jewels; but no more ivories. The ivories discovered by Layard, Loftus, Mallowan, and others were taken to England and held primarily by the British Institute. In 2011 CE, 6,000 of these ivories were sold to the British Museum for 1.17 million pounds, the highest price paid for an acquisition since the museum purchased The Queen of the Night plaque for 1.15 million pounds in 2003 CE. The ivories are now on display in numerous museums around the world including The Sulaymaniya Museum in Slemani, Iraq; The National Museum in Baghdad, Iraq; The British Museum, London; and The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, USA. They remain among the most fascinating and beautiful artifacts to come from the region of the Near East as they not only shed light on the tastes and daily lives of Assyrian royalty and nobility but bear testimony to the skill, vision, and craftsmanship of the ancient ivory-carvers.