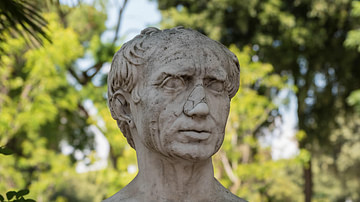

For centuries, Lucius Cornelius Sulla has been reviled as a maniacal tyrant who defiled the Roman constitution and instituted bloody purges, but some modern historians assert that he has been judged too harshly. They present him as a republican champion who predominantly acted out of necessity and often with the best of intentions. As always, the truth is more complex.

Sulla was born in 138 BCE to a Patrician family that had become largely insignificant. Although educated, he lived in relative poverty in his early adulthood and milled about with actors, but his fortunes soon changed as his stepmother and mistress both died, bequeathing him considerable wealth. This permitted him to successfully campaign for the quaestorship of 107 BCE and gain military experience. He was promptly selected to serve as one of General Gaius Marius' lieutenants in the war against the ever-elusive and increasingly dangerous former Roman ally, the Numidian king, Jugurtha.

Jugurthine & Barbarian Wars

Sulla raised and ably led a cavalry contingent during the Numidian campaign, during which he won great popularity within the ranks for sharing the common legionary's hardships. As Marius gradually captured Jugurthine strongholds and routed his armies, he tasked Sulla with negotiating with the vacillating King Bocchus of Mauretania whose allegiance was subject to change. Eventually, Bocchus agreed to surrender Jugurtha personally to Sulla, which essentially marked the end of the conflict in 105 BCE.

Sulla took every opportunity to boast that it was he who actually ended the war, not Marius, which undoubtedly annoyed the general. Nonetheless, more serious matters required their attention. Barbarian tribes from the north had humiliated multiple Roman armies and were threatening to invade the Italian peninsula. Marius was charged with subduing these tribes, the Cimbri and the Teutones, and he again chose the very capable Sulla to assist him. However, during the barbarian conflict, the relationship between Marius and Sulla became so strained that Sulla requested to be reassigned to another army, led by the co-Consul Catulus. The transfer was approved, and once more Sulla proved his worth, even though Catulus' army was relegated to a supporting role in the conflict, which ultimately resulted in the sound defeat of the barbarian tribes in 101 BCE.

Sulla's Political Ambitions

With the Jugurthine and barbarian wars concluded, Sulla focused his energy on advancing his political career. In 99 BCE, he unsuccessfully canvassed for the praetorship on his military successes. Undeterred by this loss, he sought the office again the following year on a platform of unprecedented free games, and unsurprisingly, he was duly elected. Following his praetorship, Sulla was assigned to serve as governor of the Roman province of Cilicia beginning in 96 BCE, where he displayed his administrative aptitude and military prowess.

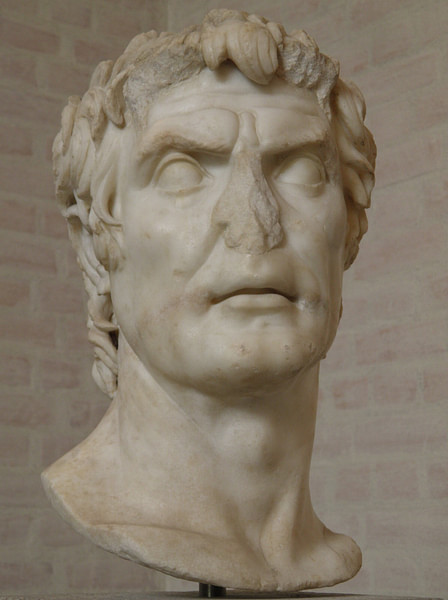

Sulla as Consul

But Sulla's political ambitions abruptly halted as Rome descended into its first civil war in 91 BCE, called the Social War. Rome's Italian allies had clamored for Roman citizenship for years and finally revolted to gain their independence. Sulla plunged himself into the conflict, briefly fought alongside Marius, and impressively neutralized many foes, gaining great notoriety. Because of his newfound popularity, he was nearly unanimously elected to the consulship of 88 BCE. However, domestic politics proved difficult to maneuver, and factional disagreements led to an outbreak of violent rioting. It became so dangerous that Sulla was forced to seek refuge in Marius' home even though he was aiding Sulla's opposition.

All the while, a threat was rapidly developing in the east. King Mithridates of Pontus had invaded the Roman province of Asia and orchestrated the massacre of 80,000 Romans and Italians. This required swift action, and the highly sought command fell to Sulla, which enraged the envious Marius. When Sulla departed to prepare his army in 88 BCE, Marius engineered the passage of legislation replacing Sulla with himself as the head of the command. Marius swiftly dispatched subordinates to facilitate the transfer of power, but they were stoned to death by Sulla's troops. The pro-Marian faction responded just as viciously by executing some of Sulla's supporters in Rome.

Sulla refused to relinquish his coveted command and decided to consolidate his position in Rome. He reversed his troops and became the first Roman general to lead a hostile army across Rome's pomerium (a sacred boundary surrounding Rome) and seize the city. Marius was not expecting such an unparalleled enterprise and was only able to coordinate a limited but insufficient defense. Marius fled the city as Sulla proclaimed him and eleven of his associates public enemies, carrying a sentence of death, but only one public enemy was captured and killed, Sulpicius. He was betrayed by his slave who, on Sulla's orders, was first granted his freedom and then thrown to his death from the Tarpeian Rock for his betraying his master.

Sulla used his unlimited power to unilaterally reform the Republic into his ideal form of government.

Once Sulla was satisfied that a favorable government was installed, he departed in 87 BCE to confront Mithridates whose control and influence had swiftly spread throughout the east, but Sulla's plans were quickly thwarted. The Consul Lucius Cornelius Cinna allied himself with Marius who returned, and they began dispensing revenge. Sulla was declared a public enemy, and many of his friends and allies were executed in a purge conducted by the pro-Marian government. They even dispatched newly raised legions to vanquish Mithridates' army. Undaunted, Sulla successfully engaged the Mithradic generals, eventually forcing a hasty but very lenient peace treaty with Mithridates. With the conflict settled, the army commissioned by Cinna defected to Sulla. He was now free to settle matters in Rome.

Meanwhile, Sulla's most implacable foe, Marius, died in 86 BCE, possibly of pleurisy, and his partner Cinna was murdered by mutinying troops in 84 BCE who were preparing to depart for Greece to eventually meet Sulla in battle. Still, the Marian faction was not yet defeated, but it increasingly relied on the leadership of junior partners.

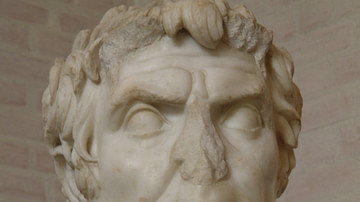

Sulla as Dictator

By 83 BCE, Sulla marched towards Rome at the head of an army intent on seizing control of the Republic's capital to eliminate potential threats and enforce his will for a second time. What resulted was another civil war that climaxed (but didn't end) just outside of Rome – at the Colline Gate – with the aid of two newcomers, Pompey and Crassus. After his victory, some opposing legionaries were granted clemency, but others were not so fortunate as he butchered thousands of soldiers who had already surrendered. By 82 BCE, Sulla assumed the dictatorship for an indefinite period of time as he saw fit. The Roman Constitution permitted the appointment of a dictator in times of dire emergencies but only for a maximum period of 6 months; it had been unused for 120 years.

Sulla used his unlimited power to unilaterally reform the Republic into his ideal form of government. He curtailed the power of the tribunes of the people who were sacrosanct elected officials with immense veto powers and the ability to circumvent the Senate by introducing legislation directly to the People's Assembly. Sulla restricted their power by requiring all legislation to first be approved by the Senate, greatly increasing its influence. He established the requisite ages for officeholders and the order in which the offices could be held along the cursus honorum (the Roman political ladder), and he packed the Senate with his supporters. He set the maximum prices for many goods, services, and also limited interest rates. He even sold tax immunity to certain cities, and he unpopularly abolished the grain dole. For all of his efforts, many of his reforms were quickly repealed, some by his allies, Pompey and Crassus.

If this was the extent of his dictatorship, then perhaps he would be remembered differently, but Sulla instituted the proscriptions, which cemented his transformation into a bloody tyrant. Each day, he posted a list of condemned Romans in the forum whose property was to be confiscated and whose murder would be rewarded with a bounty from the state. Once the deed was done, Sulla personally inspected the severed heads of the slain, which served as decorations for his home and the forum. Thousands were added to the proscription lists with or without just cause. A young Julius Caesar was proscribed for no other reason than he refused to divorce his wife, Cinna's daughter. Sulla's deputy, Crassus, placed men on the proscription lists simply because he coveted their estates, and various names were posthumously added to justify their unauthorized murders. The purge lasted for months and led to the deaths of an uncertain number from Rome's upper classes, estimated at perhaps 1,000-9,000 killed. However, under Sulla's rule, the deceased were also at risk. He ordered the corpse of his nemesis Marius to be removed from its crypt, dragged throughout the city, and torn to pieces.

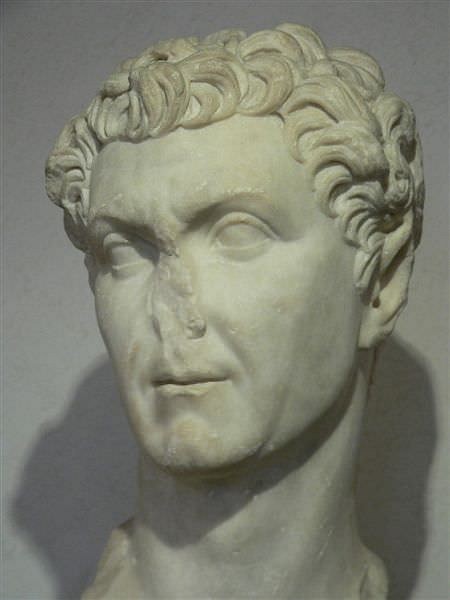

In 81 BCE, when Sulla was convinced that he had created a stable government and eradicated all potential threats, he technically resigned from the dictatorship. However, he remained in power by serving as consul for 80 BCE, but after his term, he settled into partial retirement. As he set aside ultimate authority, a man ostensibly bombarded him with insults, but the once violent dictator passively received the abuse and exclaimed, “This yob will ensure that no-one else will ever relinquish supreme power.”

One day during 78 BCE, while screaming for a corrupt official's strangulation, he began to hemorrhage orally and died the following morning, likely caused by chronic alcohol abuse. His remains were interred into his tomb with an epitaph purportedly written by Sulla himself that roughly read: “No friend ever served me, and no enemy ever wronged me, whom I have not repaid in full.”

Sulla steadfastly defended Rome, its interests, and the republican status quo for much of his career, and if that was the breadth of his life's work, then he would undoubtedly be hailed as a heroic guardian of the Republic. However, his exploits went far beyond this. He allegedly wanted to repair the fragile republican government, but he implemented reforms through brutal force. He violently, unnecessarily, and unconstitutionally seized control of the government and presided over a reign of indiscriminate terror, a lesson for future power-hungry generals, including Julius Caesar. In truth, many of the escalating domestic conflicts of this period could have easily been avoided, but Rome was simply not large enough for the competing petty egos of both Marius and Sulla.