The 30 caves at Ajanta lie to the north of Aurangabad in the Indhyadri range of Western Ghats. The caves, famous for their temple architecture and many delicately drawn murals, are located in a 76 m high, horseshoe-shaped escarpment overlooking the Waghora (tiger) River. The Ajanta Caves are listed by UNESCO as World Heritage Site.

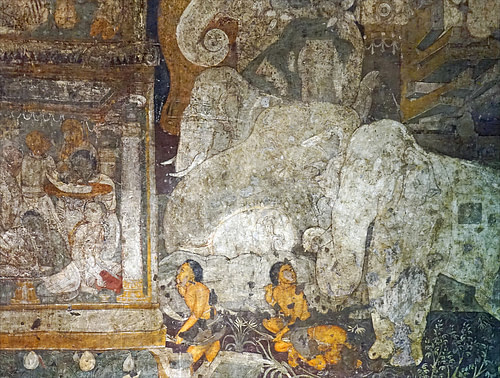

Cave 1

This is a vihara (monastery), therefore squarish in plan consisting of an open courtyard and verandah with cells on each side, a central hall sided by 14 cells, a vestibule and garbha griha (inner sanctum). Though located at a less than an ideal position of eastern extremity of the ravine its beautifully executed paintings, sculptural and architectural motifs make this cave truly fit for a king; for this is the “regal” cave patronised by Emperor Harisena.

It contains the famed paintings of Bodhisvattas Padmapani and Vajrapani along with a seated figure of Buddha in dharma chakra pravartana mudra in the sanctum. Other notable features include murals that depict Sibi, Samkhapala, Mahajanaka, Mahaummagga, Champeyya Jatakas and temptation of Mara.

Cave 2

This vihara consists of a porch with cells on either side, a pillared hall bound by ten cells, an antechamber and garbha griha. Most importantly this cave contains two sub-shrines. Buddha in the main shrine is flanked by two yaksha figures (Sankhanidhi and Padmanidhi) on the left and two others (Hariti & her consort Pancika) on the right. Beautifully decorated cave walls and ceiling portray Vidhurapandita & Ruru Jatakas and miracle of Sravasti, Ashtabhaya Avalokitesvara and the dream of Maya.

Cave 3

This is an incomplete vihara consisting only of a pillared verandah.

Cave 4

The largest vihara in Ajanta has its façade richly ornamented with sculpted figure of Bodhisvatta as a reliever of eight great perils among others. As usual, the construction follows the basic pattern of a pillared verandah with adjoining cells leading to a central hall sided by another group of cells, an antechamber and finally garbha griha. An interesting geological feature here is notable on the ceiling which gives a unique impression of a lava flow.

Cave 5

This is an unfinished excavation that proceeded only to carve out a porch and for the most part an incomplete interior hall. By the standards of Ajanta this structure is denuded of any architectural and sculptural motifs save the ornate door frame detailing female figures of makaras.

Cave 6

This two storied structure is referred to as Cave 6 Lower and Cave 6 Upper. Both stories contain an enshrined Buddha. The pillared porch, if there was any, of Cave 6 Lower does not survive today. It is also believed that the upper floor was an afterthought when the excavation of the lower level was well underway. There are some striking examples of murals preserved in the shrine and antechamber of the lower cave. In both the caves, Buddha is seen in various moods.

Cave 7

This vihara consists of two small porticoes supported by octagonal pillars with eight cells, a central hall rather oblong in shape and the garbha griha with Buddha in preaching pose. Sculptures abound, one of the more notable panels depicts a seated Buddha sheltered by Naga Muchalinda (the many-headed snake king).

Cave 8

Perhaps the earliest monastery, belonging to the Satvahana phase of excavation, this cave is located at the lowest level and a major portion from the front of the structure has been swept away by a landslide. Few architectural details survive but, importantly, the sanctum does not contain an image of Buddha.

Cave 9

Excavated in the 1st century BCE, this is one of the oldest chaitya (prayer halls) in Ajanta. The nave is flanked by aisles on either side separated by a row of 23 pillars with the stupa at the far end. The ceiling of the nave is vaulted but that of the aisles is flat. The stupa stands on a high cylindrical base at the centre of the apse. Signs of wooden rafters and beams on the ceiling, façade and tapered octagonal pillars show an adherence to the contemporary wooden architectural style. The paintings here belong to two different eras - the first being at the time of excavation while a repainting of the cave interior was carried out in the later phase of activity, around the 5th century CE.

Cave 10

This is the earliest chaitya in the cave complex having been built in 2nd century BCE. The nave is separated from the aisles by 39 octagonal pillars with the stupa being located at the apsidal end. Having been repainted in the later phase the cave contains paintings from two different periods. The scenes depict worship of Bodhi tree and stories from Sama and Chhaddanta Jatakas. The heavy begriming of the surface reveal that it was in use together with cave 9 over the centuries, though perhaps not continuously. A Brahmi inscription reads that the façade was a gift of “Vasithiputa Katahadi.”

Cave 11

This is a vihara, datable to the early 5th century CE, typically consisting of a pillared verandah with four cells, a hall with six cells and a long bench and the garbha griha which, besides the image of Buddha in preaching attitude, also contains an unfinished stupa.

Cave 12

Paleographically datable from the 2nd to 1st century BCE, this vihara was probably excavated slightly after Cave 10. The front of this monastery has collapsed completely. Only the central hall with four cells in each of its three inner sides remains. Each cell is provided with double beds with raised stone pillows. The cell frontage is ornamented with chaitya window motifs above each door. An inscription records this monastery to be a gift of a merchant named Ghanamadada.

Cave 13

This is a rather small vihara from the first phase, possibly 1st century CE, consisting of a central astylar hall with seven adjoining cells distributed on three sides.

Cave 14

Excavated above cave 13, this is an unfinished vihara. Though initially planned on a large scale it hardly progressed beyond the front half. A beautiful depiction of Salabhanjika (a woman breaking a branch of a Shorea tree) on the top corner of the doorway is to be noted.

Cave 15

This vihara was excavated around the middle of the 5th century CE. The plan follows the general vihara format of pillared porch with a cell at each end, an astylar hall accompanied by eight cells, an antechamber and finally a sanctum sanctorum with a sculpture of Buddha.

Cave 15A

This peculiar numbering is due to the fact that this was hidden under the rubble when the caves were being counted. This is the smallest vihara in Ajanta belonging to the early phase of excavation. It consists of a small central astylar hall with one cell on each side. Inside, the hall is relieved following the chaitya window pattern.

Cave 16

It is one of the largest excavations located at the centre of the arc of the ravine. An inscription records it to be a gift of the imperial Prime Minister Varahadeva. The colossal hall is surrounded by 14 cells. The garbha griha contains a sculpted figure of Buddha in pralamba padasana mudra. Some of the finest examples of murals are preserved here. Narratives include various Jataka stories such as Hasti, Maha Ummagga, Maha Sutasoma; other depictions include conversion of Nanda, miracle of Sravasti, dream of Maya and other incidents from the life of Buddha.

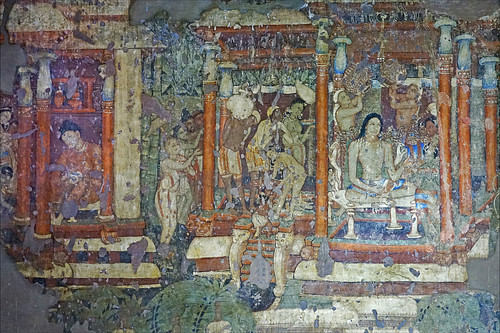

Cave 17

An exemplary collection of paintings and architectural motifs is preserved in this vihara. Excavated under the benefaction of local feudatory Lord Upendragupta, this monastery typically consists of a pillared verandah with cells on either side, a large central hall supported by 20 octagonal pillars and bounded by 17 cells, an antechamber and the garbha griha with an enshrined image of Buddha.

Among the murals the profoundly poignant illustration of Chhaddanta Jataka, exquisite ornamentation of pillars and pilasters, the sublime depiction of graceful beauty of a lady looking at herself in a mirror and the evocative retelling of subjugation of Nalagari by Buddha are some of the highlights. Many Jataka stories are depicted here including Chhaddanta, Mahakapi (in two versions), Hasti, Hamsa, Vessantara, Maha Sutasoma, Sarabha miga, Machchha, Mati Posaka, Sama, Mahisa, Valahass, Sibi, Ruru and Nigrodhamiga.

Cave 18

This was mistakenly counted as a cave. It is a porch with two pillars having moulded bases and octagonal shafts.

Cave 19

The façade of this chaitya is splendidly decorated with various carved figures and decorative motifs. Buddha offering his begging bowl to his son Rahul is depicted close to the entry door. Also, two life size yaksha figures are sculpted on either side of the chaitya arch. Inside, the apsidal plan divides the space into a nave separated by a colonnade of 17 pillars from aisles with the apse at the terminal end housing the stupa. A standing figure of Buddha is carved at the front of the stupa whose umbrella-like crown almost touches the vaulted roof. The triforium is elaborated with figures of Buddha in different poses. The aisle walls still preserve some very beautiful mural paintings. Interestingly, the courtyard outside is flanked by two side porches.

Cave 20

Possibly donated by Upendragupta, this vihara consists of a verandah with a cell on each side and the interior hall is flanked by two cells on each side. The garbha griha houses Buddha in preaching attitude. A sculptural panel of note here depicts seven Buddhas accompanied by their attendants. Most interestingly, the central hall is astylar and the antechamber advances into the hall.

Cave 21

This vihara consists of a verandah with restored pillars, a hall with 12 pillars accompanied cells in equal numbers. Out of these 12 cells, four are supplied with pillared porches. Buddha in dharma chakra pravartana mudra is sculpted in the garbha griha and traces of paintings on the wall show Buddha preaching a congregation.

Cave 22

The central hall of this vihara is astylar in form bounded by four unfinished cells. Carved in the back wall of the shrine Buddha is depicted in pralamba padasana mudra. Painted figures of Manushi Buddhas with Maitreya can also be noticed here.

Cave 23

Though unfinished this vihara is renowned for its intricately carved pillars and pilasters and naga (snake) doorkeepers. The whole structure comprises a verandah with cells at each end, an astylar hall with four cells, an antechamber with side cells, and the garbha griha.

Cave 24

Another incomplete vihara but the second largest excavation after Cave 4. The garbha griha houses a Buddha in pralamba padasana mudra but the cells bounding the central hall are unfinished.

Cave 25

An unfinished excavation at a higher level, the astylar central hall is not bound by any cell, also it is devoid of a garbha griha.

Cave 26

This chaitya is famous for its striking depiction of Mahaparinirvana (demise) of Buddha on the left aisle wall along with the assault of Mara during Buddha's penance. Quite comparable to cave 17 but of grander and more elaborate design, an inscription on the front verandah records it to be a gift of Buddhabhadra, a friend of Asmaka minister Bhavviraja. The façade, inner pillars, trifolium, and aisle walls are all skilfully decorated. The stupa has a sculpted figure of Buddha in pralamba padasana mudra.

Cave 27

Possibly a part of Cave 26, this two-storied structure is a vihara. The upper storey is partially collapsed while the lower storey consists of an inner hall with four cells, an antechamber and garbha griha with an enshrined image of Buddha.

Cave 28

This is an unfinished vihara whose pillared verandah was only excavated before being abandoned. The cave is now inaccessible.

Cave 29

An unfinished chaitya, located at the highest level between Cave 20 and 21. This cave too is now unreachable.

Cave 30

This vihara was discovered during debris clearance between Caves 15 and 16. A small structure with a narrow opening, the inside hall is bounded by three cells.

Rediscovery & Preservation

After centuries of neglect and desertion, the caves were accidentally discovered by John Smith, a member of a British hunting party in 1819 CE. With growing popularity within a few years of its rediscovery the once nondescript ravine became a soft target for unscrupulous treasure hunters. Before long, however, Indian antiquarian, archaeologist and architectural historian James Fergusson took a keen interest in their study, preservation and categorisation. It was he who commissioned Major Robert Gill to make reproductions of the paintings and together with James Burgess also numbered the caves.

Major Gill worked on 30 large scale canvases from 1844 to 1863 CE. These were displayed at the Crystal Palace in Sydenham, however, most of these paintings were soon destroyed in a fire in 1866 CE. John Griffiths, principal of the Bombay School of Art, was next commissioned to make copies of the paintings from 1872 CE onwards. It took him thirteen years to complete the project, but disaster struck yet again and well over a hundred canvases were incinerated in 1875 CE at the Imperial Institute.

Over the following decades Lady Christiana Herringham, Kampo Arai and Mukul Dey made noteworthy attempts at copying the paintings.

- Following the initiative of Ananda Coomeraswamy and William Rothenstein, Lady Herringham undertook the project and arrived at the site in 1910 CE. She was assisted by a team of contributors which included contemporary Indian artists Nandalal Bose and Asit Kumar Haldar among others. Lady Herringham worked mainly during the winter of 1910 – 1911 CE. The completed pictures were exhibited in 1915 CE by Indian Societies of Calcutta and London.

- Kampo Arai arrived in Santiniketan in the year 1916 CE; later he too proceeded to study and make copies of the murals of Ajanta. By a curious turn of fate his reproductions too were ruined while in storage at the Tokyo Imperial University following the earthquake of 1923 CE.

- Through an independent initiative noted Indian artist and photographer Mukul Dey visited Ajanta in early 1919 CE where he spent the next nine months making copies of the paintings. The experiences and adventures of this trip are fondly recollected in his book My Pilgrimages to Ajanta and Bagh.

- The celebrated Indian archaeologist Ghulam Yazdani worked tirelessly for many years from around 1920's CE for restoration and conservation of the caves and also made a comprehensive photographic survey of Ajanta.

Over a century and a half has passed since comprehensive scholarly studies were first undertaken at Ajanta. Any attempt to list the countless individuals whose unflagging pursuits to record, decipher and understand the many untold mysteries of the site, would be grossly incomplete. Nonetheless, pioneering work of a few individuals do stand out from a background of a teeming multitude. So, the following lines record the names of the historians and archaeologists whose patient work has illuminated many a dark niches and made it available to laity and connoisseurs alike.

- In the field of epigraphy, it was James Prinsep who first reproduced a few of the many inscriptions (over ninety has been recorded) in 1836 CE. Bhau Daji translated and added upon this collection when he visited the caves in 1863 CE. Other significant attempts that followed were by Bhagwan Lal Indraji, Georg Bühler, B Chhabra and Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi.

- Chronological study of Ajanta has become conterminous with Walter M Spink. Over a prolific career spanning five decades or more, he has meticulously reconstructed phase by phase the excavations of the later era under Vakataka Emperor Harisena. His comprehensive research has significantly reduced the arbitrariness of the dates and shed light on the many sociological and political influences that shaped the course of history in Ajanta.

- Dieter Schlingloff is widely recognized for his extensive study of the murals of Ajanta. Identification of the many tales of Jataka, their interpretation, iconographic significance and ties with Buddhist religion has been his life work. In many cases he has also received the able support of Monika Zin.

- Under Manager Rajdeo Singh, chief conservationist of ASI, over the last decade and a half, a painstaking restoration of the paintings of the caves 9 & 10 has been undertaken with marked success. Some of the murals that have lain hidden under grime, dust and misguided restoration efforts of a century ago can now be appreciated in their full beauty.

Though much has been irreparably damaged, a few debatable and, in all possibility, misplaced inferences have been drawn, it is through the combined efforts of many artists, archaeologists, historians, conservationists, geologists and antiquarians that the caves of Ajanta with all its grandeur and compassionate attitude continue to enthral and comfort the nameless many.