Citizenship is and always has been a valued possession of any individual. When one studies the majority of ancient empires one finds that the concept of citizenship, in any form, was non-existent. The people in these societies did not and could not participate in the affairs of their government. These governments were either theocratic or under the control of a non-elected sovereign, answerable to no one except himself. There was no representative body or elected officials. The Athenians were among the first societies to have anything remotely close to our present-day concept of citizenship. Later, the Romans created a system of government that sought the participation of its citizenry. Every citizen, women excluded, shared fully in all governmental activities with all of its rights, privileges, and responsibilities. It should be noted that Roman women were considered citizens; however, they had few, if any, legal rights.

Citizenship in the Early Republic

After the collapse of the old monarchy and the foundation of the Republic, the control of Roman government was restricted to a handful of great families - the patricians, a word derived from patres or 'fathers'. The remaining residents/citizens were called plebians, representing the poor as well as many of the city's wealthy. Soon, however, these plebians or plebs began to resent their second-class status and rose up, demanding to participate in the affairs of state and exercise their rights as full citizens of Rome. After the threat of a work stoppage became a reality, the resulting compromise - the “Conflict of Orders” - brought into creation the Concilium Plebis or Council of the Plebs. This representative body spoke for the plebians through a number of elected tribunes. It enacted laws that pertained initially to the plebians but eventually became binding to all citizens, including the patricians.

During the early days of the Republic, the Roman government was established with the primary goal of avoiding the return of a king. Its authority centered on a number of elected magistrates (consuls, praetors, quaestors and aediles), a Senate, and a number of smaller assemblies. This new concept of citizenship, however, did not mean full equality. The differences between patrician and plebian still existed. In 450 BCE the creation of the Twelve Tables, the first Roman law code, established rules that governed, among other things, the relationship between the two classes. The reward of citizenship only meant that an individual lived under the “rule of law” and had a vested interest in his government. One must wonder why there was this desire to vote or, in other words, to be a true Roman (civitas Romanus sum) - that is to say proudly “I am a Roman citizen.”

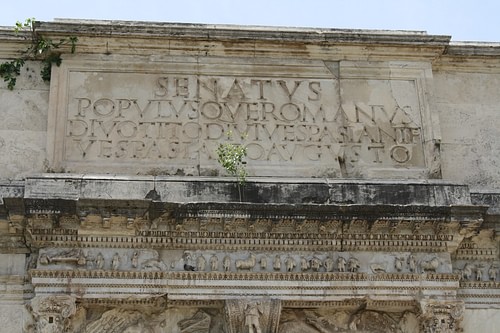

SPQR

The notion of Roman citizenship can best be represented in the logo - seen on documents, monuments and even the standards of the Roman legion - SPQR or Senatus Populus Que Romanus, the Senate and Roman People. The historian Tom Holland, in his book Rubicon, wrote that the right to vote was a sign of a person's success. To be a Roman citizen an individual was educated to “temper” his “competitive instincts” for the good of the people. For the typical Roman, the concept of “civitas” meant that he had to not only share in the joys of self-government but also suffer along in its sorrows and fears. Even the poorest of Roman citizens, the proletarii, were still represented (albeit with little effect) in the comitia centuriata.

Aside from the fact that women, although citizens, had no share in the politics of Rome, there was an even larger but significant portion of the population that resided behind the wall of the city and was not granted the rights of citizenship - the slaves. Slavery was not uncommon in the ancient world and existed long before the Republic. It could be found in the empires of Assyria and Babylon as well as in Greece. As with other civilizations, in Rome, many of the slaves came from military conquests. Slavery allowed many of the wealthy citizens to participate in the politics of running the empire. Slaves served a variety of functions. They were farmers, miners, domestic servants, entertainers and even teachers. However, unlike the slaves of Greece, a Roman slave lived in a unique society: he could earn or buy his freedom or liberti and enjoy the benefits of citizenship, gaining wealth and power; his children could even hold public office.

Empire: Expanding Citizenship

With the growth of Rome and its desire to extend its boundaries beyond the city walls, the concept of Roman citizenship changed. This growth begged the question: how were these newly conquered people to be treated? Were they to become Roman citizens? Were they to be considered equals? Despite the fact that Rome had always been a city of immigrants, the acquisition of citizenship for a resident of Rome was different for the person outside of Rome. As one historian stated, there was a difference between granting citizenship to an individual than to an entire people. After the conquest of the Latins and the Samnites, the questions of “rights” and “privileges” came into play.

While they continued to be citizens of their own communities, these new allies wanted the same freedoms as all Romans. Although they received many benefits from their position as an ally such as protection from invasion, a share of plunder from a military engagement and the ability to make economic agreements, they were not treated as true citizens of the Republic. There were disadvantages: they had to pay tribute to Rome as well as provide soldiers, indeed, by 100 BCE allies composed two-thirds of the Roman army. They subsisted in a vague second-class status called ius Latii. They had many of the benefits of a citizen but without representation in any of the city's assemblies. To be a true and equal citizen, in short, to be a Roman, an individual needed to exercise his right to vote.

By the time of the invasion of Italy by the Carthaginian general Hannibal in the Second Punic War (218 – 201 BCE) there had been some minor changes - residents of these allied communities had gained the right of conubium where the child of a Roman father and provincial mother was considered a Roman - the child was no longer considered illegitimate. A provincial (a resident of one of the provinces) could receive citizenship for his loyalty or service to the state. Later, around 150 BCE, magistrates of these Latin towns or municipia acquired Roman citizenship. And, finally, any Latin who settled in the city of Rome could obtain citizenship.

As Rome acquired lands throughout the peninsula, tensions continued to grow in many of the communities outside Rome. These newly conquered people were demanding a change in their status. While they could intermarry with Romans, make contracts and had free movement - civitas sine suffragio or citizenship without the vote - they still demanded more. They wanted what the citizens of the city had: optimo iure or citizenship with the vote. The tribune Gaius Gracchus (122 -121 BCE) made a proposal that would have granted full citizenship to all of the Italian allies. Gaius, unfortunately, faced opposition from the most unlikely of allies - the nobility and the plebians - the latter feared the competition for food and jobs. Unfortunately, Gaius's other reform suggestions made him popular with some but the enemy of others (the Roman Senate). His death and the murder of 3,000 of his followers put an end to his proposition.

The Social Wars

Change, however, was on the horizon. The Social Wars, or War of the Allies, would alter the status of the allies. While his fellow Romans in the Senate were making further attempts at restricting citizenship for the allied communities, the tribune M. Livius Drusus was proposing to grant them full and equal citizenship. In 91 BCE his assassination initiated the Social Wars (91 – 89 BCE) - one of the deadliest in all of Roman history. The Etruscans and Umbrians were threatening to secede. Riots and unrest (even outside the Italian peninsula) soon followed. The Senate told the populace that if these people became citizens they would overrun the city. However, calmer minds prevailed and as a result, full citizenship was finally granted to all people (slaves excluded) in the entire Italian peninsula (at least initially) for those who had not taken up arms against Rome. Later, Julius Caesar, the dictator for life, would extend citizenship beyond Italy and grant it to the people of Spain and Gaul.

Citizenship: Dominance of the Wealthy

The definition of what is was to be Roman was changing; in fact, the idea of what was “Latin” was becoming, as one historian expressed, less ethnic and more political. And, in Rome, many of the old questions arose such as how were the existing institutions to deal with these new citizens. These new citizens were to learn what it was to be called a Roman. Historian Tom Holland said that to be a Roman citizen meant that a person realized that he was truly free. However, there were stipulations placed on this new citizenship. The Roman citizen, whether inside or outside the city, must put aside the sense of the individual and focus on the good of the community.

In actuality, the acquisition of the right to vote by those outside the city had little meaning to all but the wealthy. Membership in the Roman assemblies was not done by election - it was a direct democracy. Voting was done by tribes, and all citizens were assigned to a particular tribe (often based on wealth) where each tribe voted as one. However, to vote a person had to appear in person which was something only the wealthy could afford to do. But citizenship was not eternal. If necessary, an individual's citizenship could be revoked; this latter condition was mostly reserved for criminals.

Every five years a citizen had to register himself at the Villa Publica for the census, declaring the name of his wife, the number of children, and all of his property and possessions (even his wife's clothes and jewels were declared). Every Roman citizen believed the government had a right to know this information. All of this data was reviewed and evaluated by the city's magistrates (censors) who could “promote or demote each citizen according to his worth.” Tom Holland wrote on the value of the census, “Classes, centuries, and tribes, everything that enabled a citizen to be placed by his fellows, were all defined by the census.”

By 212 CE the Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antonius, better known as Caracalla, took steps to make all male residents of the empire full citizens (the women in these areas had the same rights as Roman women); this proposal was called the Constitutio Antoniniana. Many historians question the rationale for this sudden benevolent act. Some believe that he needed more tax revenue, and since only Roman citizens paid an inheritance tax, his purpose was clear. But in practice, by the early 3rd century CE the idea of citizenship and the “right to vote” was mostly irrelevant. The duties of the emperor replaced the function of both the Senate and assemblies and voting rights were all but non-existent. In its place Rome became divided between two groups - the honestiores or the elite and the humilores, the lower sort - there was actually no legal distinction between the two classes. Citizenship had always meant that an individual had a role in the affairs of state, but with the assassination of Caesar and the rise to power of his step-son Augustus - who the Senate awarded the title of the first citizen or princeps - the government was forever changed in Rome. Citizenship was no longer the prized possession that it once had been.