The New Fire Ceremony, also known as the Binding of the Years Ceremony, was a ritual held every 52 years in the month of November on the completion of a full cycle of the Aztec solar year (xiuhmopilli). The purpose of it was none other than to renew the sun and ensure another 52-year cycle. The New Fire Ceremony, or Toxhiuhmolpilia, as the Aztecs themselves called it, was by far the most important event in the religious calendar because, quite simply, if the ceremony failed, then the Aztec civilization would end.

The Solar Calendar

The timing of the ceremony and the number 52 were significant as this was the exact coinciding point of the first days of the two Aztec calendars which were then in simultaneous use: the ancient Mesoamerican and sacred tonalpohualli 260-day cycle and the xiuhpohualli, the Aztec 365-day solar and ceremonial calendar. In addition, every second cycle (104 years) was given even more significance as on that precise date the tonalpohualli coincided with the 52-year cycle. The Aztecs saw such time cycles as a mirror of the ancient cosmic cycles which, in Aztec mythology, had created the world. The historian Jacques Soustelle describes well the reason a ritual like the New Fire Ceremony was of such concern to the Aztecs,

At bottom the ancient Mexicans had no real confidence in the future, their fragile world was perpetually at the mercy of some disaster: there were not only the natural cataclysms and the famines, but more than that, on certain nights the monstrous divinities of the west appeared at the crossroads, and there were the wizards, those dark envoys from a mysterious world, and every fifty-two years there was the great fear that fell upon all the nations of the empire when the sun set on the last day of the 'century' and no man could tell whether it would ever rise again (114).

Xiuhtecuhtli God of Fire

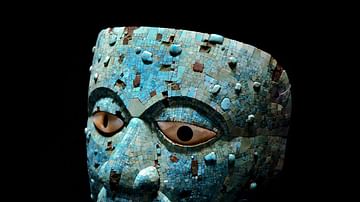

The ceremony was overseen by Xiuhtecuhtli, also known as the 'Turquoise Lord', the Aztec god of fire. His name reveals not only his association with turquoise but also with Time, as xiuhitl in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, meant both 'turquoise' and 'year'. Fire, as with many other ancient cultures, was considered a fundamental element of the universe, present in all things. Xiuhtecuhtli's pillar of fire was believed to run right through the cosmos from Mictlan, the Underworld, to Topan, the Heavens. The association between the sun and fire is made in Aztec mythology with the self-sacrifice of the gods Nanahuatzin and Tecuciztecatl who threw themselves into a fire at Teotihuacan in order to produce the Sun and Moon respectively. As we shall see, in the New Fire Ceremony one particular fire was essential to the success of ensuring the return of the life-giving sun.

Preparation For The Ceremony

Preparation for the ceremony began with the extinguishing of all fires of any kind, from temples to household hearths - the latter being especially associated with Xiuhtecuhtli. Next, a thorough cleaning operation was undertaken with the streets being swept, old hearth stones were thrown away along with old cooking utensils, old clothes too, and even idols were ceremoniously washed and cleansed. Another ritual was to tie bundles of 52 reeds together, creating a symbolic xiuhmopilli. Pregnant women were locked in granaries and their faces were painted blue in the belief that they would not then turn into monsters during the night. Children also had their faces painted and were kept from sleeping to prevent them turning into mice. Finally, as darkness fell, the populace stopped all activities, climbed the roofs of their homes and waited with a hushed silence and bated breath for what was to come.

The Ceremony

Then, just outside the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, high priests gathered at the summit of the sacred volcanic mountain south-east of Lake Tetzcoco, Mt. Uixachtecatl (also referred to as Huixachtlan or Citlaltepec and meaning 'thorn tree place', even if it is now called 'Hill of the Star'). The priests were magnificently dressed as the gods with fine cloaks, masks, and feather headdresses and led by the figure of Quetzalcoatl. Here, on a platform visible to the whole city below, the priests waited until midnight and a precise alignment of the stars which would signal the ceremony could begin. When the Tianquiztli (the Pleiades) reached their zenith and the Yohualtecuhtli star shone brightly in the very centre of the night sky, this was the moment a human sacrifice was made. The High Priest, probably dressed as Xuihtecuhtli and wearing a turquoise mask, cut out the heart from the living victim and a fire was kindled in the empty chest cavity using the sacred firestick drill, the tlequauitl. If the fire burned brightly, then all was well and Xiuhtecuhtli had blessed the people with another sun. If the fire did not catch, then the Tzitzimime would come without pity. These terrible monsters, armed with wickedly sharp knives, would roam the dark and sunless earth slashing and eating all humanity without exception. The world would end.

Fortunately, this terrible tragedy never occurred, and after each ceremony, when the fire burned well within the victim's chest, the flame was used to light a huge pyre so that all could see the success of the ceremony in the city below. Then the flames were transferred to Tenochtitlan where they were used to light the fire at the temple of Huitzilopochtli on top of the Templo Mayor pyramid. Next, the fire at the city's Fire Temple was lit and from there, runners ensured that all the fires of the city were, once again, lit.

Following the successful ceremony, hearth stones were renewed and offered incense and quails in thanks. Then, after a suitably pious morning of fasting, there was, understandably, a great deal of partying. The revellers wore new clothes, feasted on amaranth-seed and honey cakes, and drank pulque beer. A little later, Aztec rulers, buoyed by this divine endorsement of their rule, would embark on a series of state building projects such as Motecuhzoma I did in 1455 CE when he greatly enlarged the Templo Mayor at Tenochtitlan.

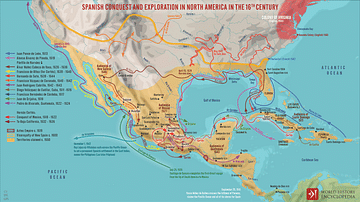

The New Fire Ceremony was successfully held in 1351, 1403, 1455, and again in 1507 CE. Curiously, although perhaps indicative of the belief that each cycle was a new beginning, the Aztecs did not specifically date different 52-year cycles. The calendar, as it were, was each time reset to zero. The last New Fire Ceremony, then, ushered in the 5th sun of the Aztec era, poignantly the last according to Aztec mythology and, with the arrival of the European invaders, so it turned out to be.

The New Fire Ceremony in Art

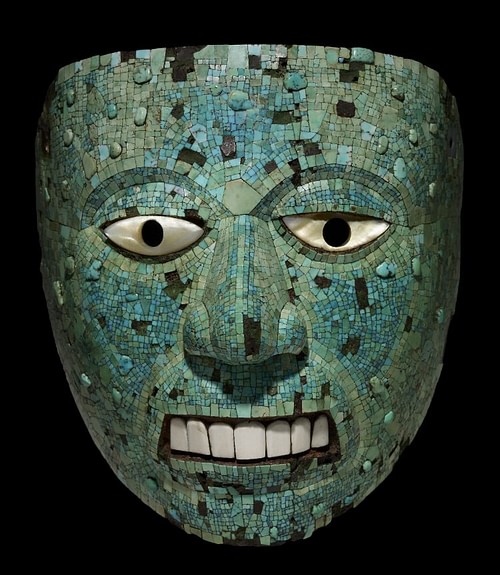

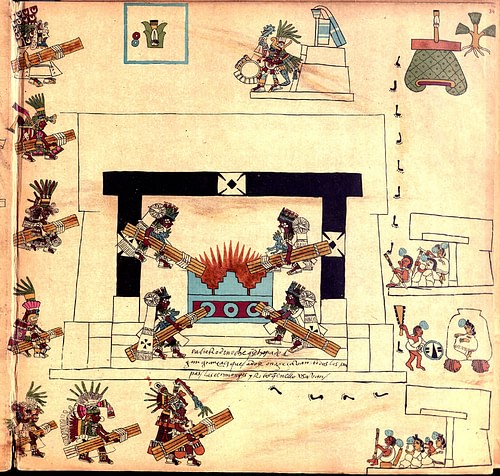

The New Fire Ceremony is referred to in various instances of Aztec and colonial art. Stone sculptures representing the xiuhmopilli bundles have been excavated at Tenochtitlan, each with a date stamp hieroglyph of the year they were produced. The ceremony of relighting the fires at Tenochtitlan is represented in an illustration in the Codex Borbonicus (Sheet 34), c. 1525 CE. Priests carry bundles to transfer the fire and they wear turquoise masks, as do other citizens, including women and children. Also included is an image of Montezuma (aka Motecuhzoma II), the Aztec ruler who presided over that final ceremony in 1507 CE.

One of the most famous of all Aztec artworks is the turquoise mosaic mask of Xiuhtecuhtli now in the British Museum. Perhaps similar to the masks worn by the High Priests in the Fire ceremony it has conch shell eyes and dates to the 14th century CE. Finally, the celebrated Throne of Motecuhzoma II was specifically sculpted to commemorate the New Fire Ceremony of 1507 CE. The throne has date glyphs carved on the front, a depiction of Xiuhtecuhtli and other gods at the sides, and the seat back carries a large sun disk.