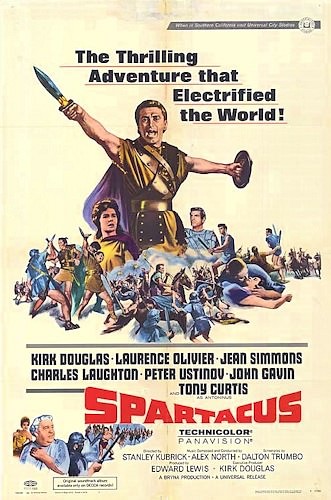

The revolt of the gladiator Spartacus in 73-71 BCE remains the most successful slave revolt in the history of Rome. The rebellion is known as the Third Servile War and was the last of three major slave revolts which Rome suppressed. The story of Spartacus has been told by historians, novelists, and filmmakers up to the present day when it enjoys a wide following as a very popular television series but admiration for the hero of the Third Servile War is nothing new. Karl Marx once noted in a letter to Engels that Spartacus was among the greatest, if not the greatest, hero of the ancient world and held him up as an example to be followed (Volume 41, 265). Stanley Kubrick's famous 1960 film Spartacus, based on the Howard Fast novel, portrayed him as a freedom fighter leading his people against the oppressive system of Roman slavery and every portrayal of the rebel gladiator which has come after Kubrick's film has followed suit to greater or lesser degrees.

The actual Spartacus, however, was not a proto-Marxian proletariat revolutionary nor a hero of his people fighting for their freedom; he was simply a man who had endured enough of the Roman institution of slavery and, one day, decided he would endure no more. The revolt of Spartacus began, more or less, as an accident; the original plan of the gladiators, according to the historian Plutarch (c. 45-120 CE), was simply to escape. Once that plan was discovered, however, they had no choice but to fight for their freedom or submit to execution.

The actual motivations behind Spartacus' revolt do not detract from his accomplishments, however. They became irrelevant starting in 18th century CE France when the gladiator became elevated to iconic status as an enemy of oppression and champion of freedom. The terrible conditions of life as a slave in ancient Rome have since been compared to those of any group suffering oppression and Spartacus is the most recognizable hero from the ancient world to serve as a symbol. In 73 BCE, however, he seems to have had no other motivation than his own freedom and escape from the punishments he could expect from his masters.

Slavery in Ancient Rome

These punishments would have been brought swiftly once his escape plan was discovered. Slavery was widespread in ancient Rome and the Romans greatly feared an uprising of their lowest working class. Historian Mark Cartwright comments on this:

Slavery was an ever-present feature of the Roman world. Slaves served in households, agriculture, mines, manufacturing workshops, construction and a wide range of services within the city. As many as 1 in 3 of the population in Italy or 1 in 5 across the empire were slaves and upon this foundation of forced labour was built the entire edifice of the Roman state and society.

Rome's economy relied chiefly on agriculture and war: farming sustained the populace while military campaigns generated necessary funds for various other needs. The soldiers used in these campaigns were farmers who were kept in the army for longer and longer periods of time as Rome expanded in conquest. Their farms would often go bankrupt and their lands were then purchased by the wealthy who used slaves to work them.

The historian Appian (c. 95-165 CE) writes, "The rich used persuasion or force to buy or seize property which adjoined their own, or any other small holdings belonging to poor men, and came to operate great ranches instead of single farms. They employed slave hands and shepherds on these estates to avoid having free men dragged off the land to serve in the army, and they derived great profit from this form of ownership too, as the slaves had many children and no liability to military service" (Civil Wars, 1.7). These slaves were brought in from a number of different sources as Cartwright notes:

Aside from the huge numbers of slaves taken as war captives (e.g. 75,000 from the First Punic War alone) slaves were also acquired via piracy, trade, brigandage and, of course, as the offspring of slaves as a child born to a slave mother (vernae) automatically became a slave irrespective of who the father was. Slave markets proliferated, perhaps one of the most notorious being the market on Delos, which was continuously supplied by the Cilician pirates. Slave markets existed in most large towns, though, and here, in a public square, slaves were paraded with signs around their necks advertising their virtues for prospective buyers.

Slaves were used for a wide array of tasks throughout Rome from field work to housework, tutoring children in reading, writing, music and other arts, personal attendants, and any other job which they could fill. They were completely at the mercy of their master. The Roman writer Seneca the Younger (4 BCE-65 CE) describes the lot of the house slave to his friend Lucilius, advocating for better treatment of slaves, and makes clear how even the smallest sound or action on the part of the slave was dictated by the master's whims. Here he describes the slave waiting on his master at dinner:

The master eats more than he can hold; his inordinate greed loads his distended belly, which has unlearned the belly's function, and the digestion of all this food requires more ado than its ingestion. But the unhappy slaves may not move their lips for so much as a word. Any murmur is checked by a rod; not even involuntary sounds - a cough, a sneeze, a choke - are exempted from the lash. If a word breaks the silence the penalty is severe. Hungry and mute, they stand through the whole night (Nardo, 51).

Seneca goes on to detail the abuses slaves suffered and the arrogance of their masters who, by their cruelty, have given rise to the proverb, "So many slaves, so many enemies." He asks Lucilius to remember that "the man you call `slave' sprang from the same seed, enjoys the same daylight, breathes like you, lives like you, dies like you" and yet these people are treated as less than human:

We abuse them as one does pack animals, not even as one abuses men. When we recline at table one slave wipes up the spit, another crouches to take up the leavings of the drunks. One carves the costly game, separating the portions by deft sweeps of a practiced hand - unhappy man, to live solely for the purpose of carving fowl neatly...another has the assignment of keeping book on the guests; he stands there, poor fellow, and watches to see whose adulation and whose intemperance of gullet or tongue will get him an invitation for the following day. Add the caterers with their refined expertise of the master's palate; they know what flavors will titillate him, what table decorations will please his fancy, what novelty might restore his appetitie when he feels nauseous, what tidbit he would crave on a particular day. With slaves like these the master cannot bear to dine; he would count it an affront to his dignity to come to table with his own slave. Heaven forbid! (Nardo, 51).

The poor treatment of slaves was so widespread it came to be regarded as natural. One needed to break the slaves' will as an individual in order to have a compliant servant who would meet the expectations of a slave in Roman society. Free labor meant greater leisure and profit for those who owned slaves but those slaves were only profitable if they were submissive and did as they were told without question or hesitation. The fact that the slave population was so great is testament to the Roman ability to maintain this kind of control over those they enslaved.

It should be noted that not all slaves were treated poorly. In Seneca's same letter, he writes of slaves who were treated well by their masters and who would give their lives to safeguard the home, property, and life of that master. Two famous philosophers were slaves, Diogenes of Sinope (c. 404-323 BCE) in Greece and Epictetus (c. 50-130 CE) in Rome and both were treated as family members. Diogenes was given complete control over the education of the boys of the house and Epictetus' master sent him to study stoic philosophy. These are notable exceptions to the general rule, however, and most slaves endured hard lives with little hope of winning their freedom and no rights under the law.

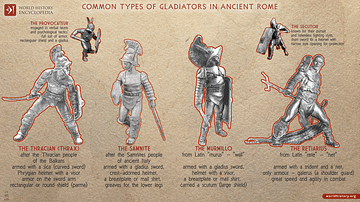

In time, there were more slaves than free people in Rome. The unemployment rate rose sharply as more and more slaves were used for jobs which Roman citizens used to hold and the countryside around the city of Rome increasingly became a vast network of slave colonies residing on large plantations of the very rich. Those slaves not employed in domestic or agricultural jobs were used as gladiators in the arena. If the life of the house-slave was bad, that of the gladiator was worse. The gladiator was a slave whose sole purpose was to fight for the entertainment of the Roman crowds. Gladiators were usually male (though there were some females) and could win freedom through exceptional feats but, most of the time, lived and died a slave in the arena. Slaves were most often selected as gladiators based on a robust physique which would be appealing to spectators; and one of these was Spartacus.

Early Life & Enslavement

Spartacus was a Thracian, originally from a region north of Macedonia, which was considered by both Greeks and Romans as uncivilized and barbaric. Spartacus, however, is described by Plutarch as "more Greek than Thracian" and notes that he was exceptionally intelligent and highly cultured. Nothing is known of his youth nor how he became a slave to Rome. The primary sources on Spartacus' revolt are the historians Appian, Florus (c. 130 CE), and Plutarch, who each select those details they found most suitable from the earlier works on the revolt by Sallust (c. 86-35 BCE) and Livy (59 BCE-17 CE), both of which exist now only in fragments.

According to Appian, he was a Thracian "who had once fought against the Romans and, after being taken prisoner and sold, had become a gladiator" (Civil Wars, I.116). Florus claims he was a Roman mercenary in the legions who was imprisoned for desertion and robbery before being selected as a gladiator "thanks to his strength". Plutarch gives a similar account of Spartacus as a mercenary for Rome but adds he was captured along with his wife after deserting. His wife is described as a prophetess of her people who escaped with Spartacus during the revolt and traveled with his army afterwards, most likely dying with him in the final clash with Rome.

Spartacus' Revolt

However he was captured, and for whatever reasons, his military training and physique made him a perfect candidate for the arena. Spartacus is described by all the ancient sources as tall and exceptionally strong. He was bought by a trainer named Lentulus Batiatus and sent to a gladiatorial school south of Rome in Capua. These schools regularly relied on harsh treatment of the slaves to prepare them for the games in the arena and this discipline, like that used with all slaves, was intended to break the individual's will and make them compliant.

In 73 BCE, Spartacus and some other conspirators devised a plan to escape from the compound and head north to freedom beyond the Apennines. This plan included over 200 other slaves and, with so many involved, it was no surprise when word was leaked to the authorities. Spartacus knew they would be tortured before they were killed and so led 78 of his fellow slaves in a revolt. They raided the kitchen and armed themselves with knives and spits and then murdered their instructors and captors. Once they were free they found more weapons in the storerooms and a transport wagon and then fled the school for the nearby countryside where they encamped somewhere on the slopes of Mount Vesuvius. There they elected Spartacus, Oenomaus, and Crixus as their leaders.

Rome's First Response

Although the slaves elected three leaders, each ancient source claims Spartacus soon became supreme commander. Appian writes, "With the gladiators Oenomaus and Crixus as his subordinates, he plundered the nearby areas, and because he divided the spoils in equal shares, his numbers quickly swelled." News of the revolt spread quickly and many of the slaves from the plantations throughout the country left their homes and joined the rebels. The Roman senate considered all of this more of a bother than a threat and sent a force of largely untrained soldiers under the general Gaius Claudius Glaber to take care of the problem.

Glaber and the senate seem to have thought that a group of runaway slaves would be easily defeated as they could not possibly know anything about military tactics or warfare. Spartacus surprised them, however. Glaber surrounded the slaves in their camp on the mountainside, keeping them penned in, and prepared to starve them into submission. The mountain was thick with vine branches, however, and Spartacus ordered his men to weave these into ladders by which they were able to climb down an area which Glaber had neglected, thinking it inaccessible, and attacked from behind Glaber's lines, defeating him and looting the camp for weapons.

A second force was then sent against the slaves led by Publius Varinus who chose to divide his forces, perhaps hoping to catch his enemy in a vice and crush them. Whatever his plan may have been is unknown but its failure was spectacular; Varinus' army was defeated and scattered. Spartacus' victory was so complete that Varinus lost even the horse he had ridden into battle. After these two victories, more slaves left their master's homes and joined the revolt.

Rome's Second Response

The Roman senate realized they had seriously underestimated Spartacus, who now commanded an army of over 70,000 former slaves, and called on the consuls Publicola and Clodianus to lead their forces against him. Spartacus controlled the countryside now with new recruits flocking to his cause almost daily. Livy notes how Spartacus' army "laid waste [the cities] of Nola, Nuceria, Thurii, and Metapontum with terrible destruction." There was no doubt now that he posed a significant threat to Rome. Spartacus had no intention of marching on Rome, however, and led his army north out of Italy to cross the Apennines and allow his followers to return to their homes. His force was too large to move singly, however, so he divided it in two and placed his second-in-command Crixus in charge of one.

The Romans under Publicola attacked Crixus' forces while Clodianus struck at Spartacus' contingent. Crixus's forces were beaten back with heavy losses but Spartacus defeated Clodianus and then drove Publicola from the field. Crixus was killed in the battle and Spartacus honored him by sacrificing 300 Roman prisoners (according to Appian). He then held his own gladiatorial shows using the remaining Roman captives for the spectacle. Florus writes how he forced the Romans to fight each other at the funeral pyres of his fallen officers "just as though he wished to wipe out all his past dishonor by having become, instead of a gladiator, a giver of gladiatorial shows." He then burned all the wagons and supplies he could not use and marched toward Rome with over 120,000 infantry and an unknown number of cavalry.

Spartacus' Defeat

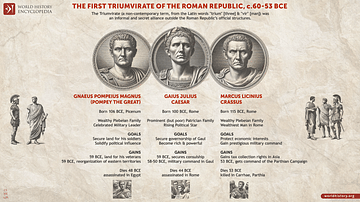

There is no record of why Spartacus abandoned his plan to lead his forces to freedom by leaving Italy but, for whatever reason, the ever-growing army of former slaves now marched south. Two more armies were sent against Spartacus and he defeated them both. Appian writes, "The war had now lasted three years and was causing the Romans great concern, although at the beginning it had been laughed at and regarded as trivial because it was against gladiators." Publicola and Clodianus were retired by the senate and a new supreme commander, Marcus Licinius Crassus, was called up. He first punished the legions for their failure through decimation where the soldiers drew lots and every tenth man was put to death.

Crassus meant to end the war quickly and, according to Appian, "established himself in the eyes of his men as more to be feared than a defeat at the hands of the enemy." Crassus marched against Spartacus at Bruttium in the far south of Italy. Spartacus' plan was to work with the Cilician pirates to take over the Roman-occupied island of Sicily and make it a free nation for his followers. The pirates were supposed to have met him at the coast of Bruttium but they never arrived. Crassus had his army of over 32,000 soldiers move quickly and build a wall which trapped Spartacus behind it.

Crassus felt confident in waiting out his opponent since Spartacus, with the sea behind him and the wall in front, had nowhere to go. Spartacus tried to break out but was driven back with the loss of over 6,000 of his men. According to Florus, Spartacus then tried to escape by launching "rafts of beams and casks bound together with ropes on the swift waters of the straits" but failed. Appian and Plutarch both claim that Spartacus resorted to guerilla tactics at this point. Appian writes how he "conducted many separate harassing operations against his besiegers" and "crucified a Roman prisoner in no man's land to demonstrate to his own troops the fate awaiting them if they were defeated." Crassus, for his part, continued to wait and let starvation and desperation do the work for his troops.

The Roman senate, however, felt that Crassus was not moving quickly enough and brought in the famous general Pompey, the conqueror of Spain. Crassus now stepped up his attacks in order to defeat Spartacus before Pompey could arrive to steal the glory. Spartacus, seeing an opportunity to divide the Roman generals before Pompey's arrival, asked to negotiate terms with Crassus but was refused.

Seeing there was no hope, Spartacus rallied his men and, according to Plutarch, "when his horse was brought to him, he drew he sword and killed it, saying that the enemy had plenty of good horses which would be his if he won and, if he lost, he would not need a horse at all." He led his army a last time into battle and, Plutarch writes, "made straight for Crassus himself, charging forward through the press of weapons and wounded men and, though he did not reach Crassus, he cut down two centurions who fell on him together. Finally, when his own men had taken to flight, he himself, surrounded by enemies, stood his ground and died fighting to the last." Appian writes, "Spartacus himself was wounded by a spear-thrust in the thigh but went down on one knee, held his shield in front of him, and fought off his attackers until he and a great number of his followers were encircled and fell" and Florus comments, "Spartacus himself fell, as became a general, fighting bravely in the front rank." Appian and Plutarch both note that his body was never identified.

Although Crassus had defeated Spartacus on the field, the glory for the victory went to Pompey. Pompey arrived as the battle was ending and his troops engaged the fugitive slaves who ran from the field. Plutarch writes that "Pompey, in his dispatch to the senate, was able to say that, while Crassus certainly had conquered the slaves in open battle, he himself had dug the war up by the roots" by eliminating any who might have continued the struggle. The 6,000 survivors of Spartacus' army were then crucified along the Appian Way from Rome to Capua and their bodies left there to rot for years as a warning against any future insurrections.

Legacy

Although the early Roman historians viewed him as a dangerous rebel and criminal, all their accounts show a grudging (and sometimes outright) respect for the gladiator-general. A war against slaves was considered a dishonor and the fact that Spartacus had prolonged the conflict so successfully for so long was especially difficult for Roman pride. Pompey was given a triumph for his victories in Spain and, almost as an afterthought, ending the Third Servile War while Crassus, for his efforts, was given the much less prestigious ovation, a foot parade with none of the spectacle of the triumph.

Even so, the tone of the narratives - especially Plutarch's account - is unmistakably admirable whenever the writers mention Spartacus' victories and, especially, in relating his death. These narratives inspired later artists to present Spartacus as a freedom fighter battling the might of Rome to end slavery even though none of the ancient accounts support this conclusion. Spartacus is clearly depicted in every version as a gladiator who sought his own freedom and wound up as leader of a slave revolt. His modern status as freedom fighter and cult hero developed much later but draws on the histories of these Roman writers.

The concept of Spartacus as the noble rebel fighting for freedom can be traced back to a French tragedy, Spartacus, written by Bernard-Joseph Saurin in 1760 CE which was inspired by Plutarch's account. Saurin was trying to draw a parallel between the oppressive conditions of ancient Rome and those of his own time in 18th century CE France. Historian Maria Wyke explains how, in the mid-18th century:

Spartacus began to be elevated in Western European literature, historiography, political rhetoric, and visual art into an idealized champion of both the oppressed and the enslaved. From this period, representations of the ancient slave rebellion and the gladiator Spartacus were profoundly driven by the political concerns of the present (36).

Saurin's very popular play was revived in 1792 CE following the French Revolution and statues of Spartacus began to appear in France as early as 1830 CE. His story was taken up by the Italian novelist Raffaello Giovagnoli in 1874 CE in his historical novel Spartacus which drew parallels between the ancient Thracian gladiator and the nationalist general Giuseppe Garibaldi who united Italy in the 1860s. Spartacus has also been compared with Toussaint L'Overture (1743-1803 CE), leader of the Haitian Revolution against French rule.

The popular understanding of Spartacus as a selfless hero grew through the works of other writers, Bertholt Brecht among them, in the 20th century CE until novelist Howard Fast wrote his historical novel Spartacus in 1951 which was used for the Stanley Kubrick film Spartacus in 1960. Kubrick's film was written by the screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, accused of being a communist and blacklisted from Hollywood. The famous scene toward the end of the film of the rebels crying out "I am Spartacus!" to protect their leader has been interpreted by critics as Trumbo's call for solidarity in resisting the oppression of McCarthyism in America (Gaylean, 1).

Fast's novel and Trumbo's screenplay have served as the template for both the 2004 TV movie Spartacus and the 2010-2013 Spartacus TV series on Starz Network as anyone acquainted with the earlier works will recognize. Since the release of Kubrick's film in 1960, Spartacus has been admired more widely than ever before as an inspirational figure for any oppressed or unfairly marginalized group in society whether through racism, sexism, or homophobia. The lone individual standing up against the oppressive might of the majority, the rebel fighting against an unjust system of laws and prejudices, this was the Spartacus to inspire a cause; not a Thracian slave who only sought his own freedom. Scholar Erich Gruen writes:

There is no sign that [Spartacus was] motivated by ideological concerns to overturn the social structure. The sources make clear that Spartacus endeavored to bring his forces out of Italy toward freedom rather than to reform or reverse Roman society. The achievements of Spartacus are no less formidable for that. The courage, tenacity, and ability of the Thracian gladiator who held Roman forces at bay for some two years and built a handful of followers into an assemblage of over 120,000 men can only inspire admiration (Historical Background, 3).

Whether he started his revolt in 73 BCE to end slavery in Rome and free his people no longer matters; all that matters is what he has come to symbolize. The true Spartacus - whoever he may have been - was replaced by the hero Spartacus because a hero is what people needed and continue to need. The story of the hero Spartacus will continue to inspire people for ages to come, as he has over the past 200 years, symbolizing the individual fighting for justice and freedom for his people against impossible odds.