Pets were very important to the ancient Egyptians and considered gifts from the gods to be cared for until their death when they were expected to be returned to the divine realm from which they had come. In life, pets were well cared for and, at their death, were often mummified in the same way as people.

The ancient Egyptians kept animals as pets ranging from domesticated dogs and cats to baboons, monkeys, fish, gazelles, birds (especially falcons), lions, mongoose, and hippos. Crocodiles were even kept as sacred animals in the temples of the god Sobek. Scholars disagree on whether Egyptians actually worshipped animals as deities but are unanimous when it comes to how the people of ancient Egypt felt toward their pets: domesticated animals were just as popular and deeply loved as pets are in the present day.

One famous example illustrating this attachment is the high priestess Maatkare Mutemhat of the Twenty-First Dynasty (1077 - 943 BCE). Mutemhat was the daughter of the high priest Pinedjem I (l.1070 - 1032 BCE) and sister to the pharaoh Psusennes I (r. 1047 - 1001 BCE). She followed her father's example and dedicated herself to the god Amun completely, taking the title "God's Wife" and choosing a life of celibacy when she took the praenomen (title) Maatkare ("Truth in the Soul of the Sun").

When Maatkare Mutemhat's mummy was discovered in the Theban necropolis, archaeologists found a smaller mummy, the size of a very young child, at her feet. The original interpretation was that this was her baby and she had died giving birth but this made no sense as Maatkare Mutemhat was known to be celibate. In 1968, x-rays of the smaller mummy determined it was not her child but her pet monkey. Historian Don Nardo writes:

The Egyptians were fond of animals, frequently depicting household pets in paintings and reliefs on their tomb walls. The pet-beneath-the-chair motif shows the master of the house seated with a pet cat beneath his chair. Dogs and monkeys were also frequently shown as pets. Because the Egyptians believed that the next world was a continuation of this one, and that you could 'take it with you' , it is not surprising that they had their pets mummified and included them in their tombs. (116)

Although exotic animals in egypt such as baboons, monkeys, hippos, and falcons were not uncommon, the ancient Egyptians seemed to favor the dog and cat as much as people today in the modern world. The dog was considered a very important member of the household and the cat is famously associated as the most popular Egyptian pet.

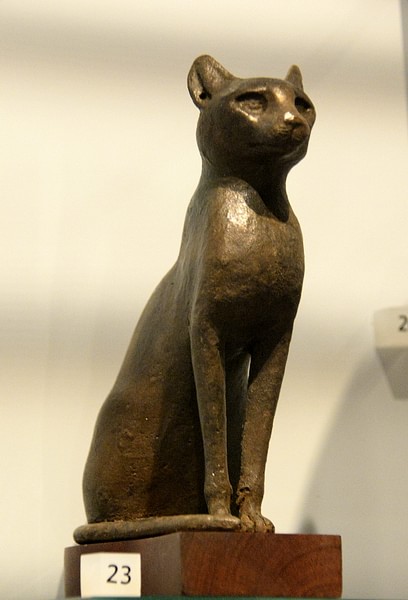

Most households, it seems, had a pet cat - often more than one - and, to a lesser degree, a dog. Cats were more popular because of their close association with the goddess Bastet but also, on a practical level, because they could take care of themselves and rid the home of pests. Dogs, requiring more care, were more often kept by the upper classes who were better able to afford them.

Dogs in Ancient Egypt

The dog was still very important to the Egyptians, no matter their social status. According to historian Jimmy Dunn, dogs "served a role in hunting, as guard and police dogs, in military actions, and as household pets" (1). The Egyptian word for dog was iwiw which referenced their bark (Dunn, 1).

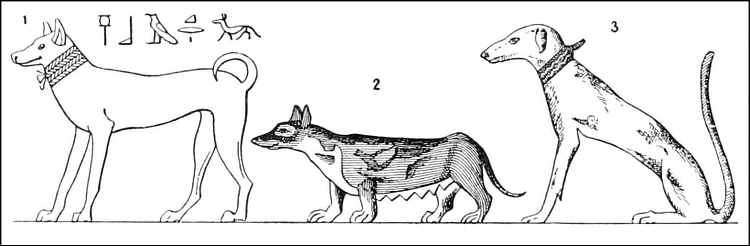

The dog breeds of ancient Egypt were the Basenji, Greyhound, Ibizan, Pharaoh, Saluki, and Whippet and dogs are referenced in the Predynastic Period of Egypt (c. 6000-3150 BCE) through rock carvings and c. 3500-3200 BCE, specifically during the Gerzean Culture (also known as Naqada II Period), in images and written text.

The Egyptians are credited with the invention of the dog collar (though it was probably first used in Mesopotamia) as an early wall painting dated c. 3500 BCE depicts a man walking his collared dog on leash. These early collars were simple leather bands but became increasingly ornate as time went on. The collars were designed in width to complement the kinds of breeds favored in Egypt. The Basenji, one of the oldest breeds in the world, is considered by some scholars to be the model for the god Anubis though the Ibizan and Pharaoh Hound are also equally qualified as is the Greyhound.

Whichever breed inspired the image, dogs were closely linked to the jackal/dog god, Anubis, who guided the soul of the deceased to the Hall of Truth where the soul would be judged by the god Osiris. Domesticated dogs were buried with great ceremony in the temple of Anubis at Saqqara and the idea behind this seemed to be to help the deceased dogs pass on easily to the afterlife (known in Egypt as the Field of Reeds) where they could continue to enjoy their lives as they had on earth. At Abydos, there was a special cemetery reserved just for dogs.

Dogs were highly valued in Egypt as part of the family and, when a dog died, the family would have the dog mummified with as much care as they would pay for a human member of the family. Great grief was displayed over the death of a family dog and the family members would shave their bodies completely, including the eyebrows. As most Egyptian men and women shaved their heads to avoid lice and maintain basic hygiene, the absence of the eyebrows was the most notable sign of grief.

Even so, it was believed that one would meet one's canine friend again in the afterlife. Tomb paintings of the pharaoh Tutankhamun show him in his chariot hunting with his dogs and Rameses the Great is also depicted similarly with his hunting dogs in the Field of Reeds; dogs were often buried with their masters, in fact, to provide this kind of companionship in the afterlife. The intimate relationship between dogs and their masters in Egypt is made clear through inscriptions in tombs, monuments, and temples and through Egyptian literature. Dunn writes:

We even know many ancient Egyptian dog's names from leather collars as well as stelae and reliefs. They included names such as Brave One, Reliable, Good Herdsman, North-Wind, Antelope and even "Useless". Other names come from the dog's color, such as Blacky, while still other dogs were given numbers for names, such as "the Fifth". Many of the names seem to represent endearment, while others convey merely the dog's abilities or capabilities. However, even as in modern times, there could be negative connotations to dogs due to their nature as servants of man. Some texts include references to prisoners as 'the king's dog'. (Dunn, 2)

Even though 'dog' could be used as an insult, many people seem to have named their dogs after people they loved, or even honored them with the names of gods. Although there is some evidence that cats were named, this practice was not as widespread as the naming of dogs. As noted, dogs were regularly buried with their masters and their names recorded. Some tombs show signs that the dog was killed at the master's death and then mummified while other dogs had died earlier than the master. In the catacombs of Saqqara, over eight million dog skeletons have been found which archaeologists have interpreted as evidence of sacrifice of dogs to Anubis but which could also simply be a necropolis for dogs.

Cats in Ancient Egypt

The Egyptians are actually responsible for the name 'cat' in that it derives from the North African word for the animal, quattah and, as the cat was so closely associated with Egypt (and Egyptian trade came to greatly influence Greece and Rome) almost every other European nation employs variations on this word: French, chat; Swedish, katt; German, katze; Italian, gatto; Spanish, gato and so forth (Morris, 175).

The colloquial word for a cat - 'puss' or 'pussy' - is also associated with Egypt in that it derives from the word Pasht, another name for the cat goddess Bastet. The cat is almost synonymous with Egypt through its association with the image of Bastet who was originally imagined as a ferocious wild cat, a lioness, but softened in time to become a housecat. Cats were prized not only for their company but their utility in that they kept the home clear of unwanted visitors such as rats and snakes.

Cats were so important to the ancient Egyptians that they literally sacrificed their country for them. In 525 BCE the Persian general Cambyses II invaded Egypt but was stopped by the Egyptian army at the city of Pelusium. The historian Polyaenus (l. 2nd century CE) writes that Cambyses II, knowing the veneration the Egyptians held for cats, had the image of Bastet painted on his soliders' shields and, further, "ranged before his front line dogs, sheep, cats, ibises and whatever other animals the Egyptians hold dear" knowing that they would not fight against images of animals they loved. The Egyptians surrendered and the country fell to the Persians. During Cambyses II's victory march he is said to have hurled live cats at the Egyptian's faces to mock them for surrendering their country for an animal.

The Egyptians did not seem to care whether a Persian understood their values or scorned them. They continued to honor the cat highly. Herodotus (l. c. 484 - 425/413 BCE) later wrote how, if a home were on fire in Egypt, the people would save the cats before saving themselves or trying to put out the fire. Herodotus also notes the custom of shaving body hair as a sign of grief:

All the inhabitants of a house where a cat has died a natural death, shave their eyebrows and, when a dog dies, they shave the whole body including the head. Cats which have died are taken to Bubastis where they are embalmed and buried in sacred receptacles; dogs are buried in sacred burial places in the cities where they belong. (II.66-67)

Some scholars have suggested that cats were ritually sacrificed to Bastet as so many mummified cats have been found in tombs but this claim is untenable. Mummified cats who were brought to Bubastis - the cult center of Bastet - were brought there in honor so they would be close to the goddess. This same paradigm can be seen in practices observed at other sites, such as Abydos, where people wanted to be buried - or at least have memorials erected - to be close to Osiris and have an easier access to the afterlife.

Claims by some writers that cats were intentionally killed as sacrifices are almost impossible to accept. The penalty for killing a cat in Egypt - even by accident - was death so it is highly unlikely that cats would be killed as a sacrifice to a goddess whose role included the protection of cats. Cats were prized at such value that it was illegal to export them. The export of cats from Egypt was so strictly prohibited that a branch of the government was formed solely to deal with this issue. Government agents were dispatched to other lands to find and return cats which had been smuggled out.

Exotic Pets

As in the example of Maatkare Mutemhat, Egyptians also kept animals which today would be considered 'exotic pets'. The falcon, for example, represented the power of gods like Horus and Montu and were highly prized as pets. Pharaohs and earlier kings kept a falcon for hunting but also as a symbol of divine power. The ibis was another popular bird of the upper class which represented wisdom and the god Thoth. These birds, generally speaking, were too expensive for the lower classes to keep but mummified remains of the ibis suggest that they were still kept fairly widely. There were 500,000 mummified ibises found at the Saqqara complex alone.

The gazelle was another popular pet one would consider exotic in the present day but, to the Egyptians, was quite common. The most famous example of a mummified pet gazelle comes from the tomb of Queen Isiemkheb of the 21st Dynasty (l. c. 1069-943 BCE). Isiemkheb (sometimes known as Isi-em-kheb) lived under the reign of the pharaoh Pinedjem II (c. 990-976 BCE) and loved her pet gazelle so much she ordered a specially crafted sarcophagus for it.

The coffin is carved with the image of the gazelle and formed to fit its body. The mummified gazelle, which was handled with the same care given to a human body, was found with Isiemkheb in her tomb and the preparations of both her mummy and her pet's, as well as the amulets found still in place, indicate there was every assurance the two would be united again in the Field of Reeds.

Baboons and monkeys were often coddled as loving companions and were mummified and buried with their devoted masters and mistresses. Baboons seem to have been kept for largely ritualistic purposes as symbols of Thoth or Hapy but monkeys were more commonly kept as close pets. Monkeys could be easily trained and inscriptions seem to indicate they were quite useful to their owners in retrieving objects.

Although these exotic pets enjoyed a fairly comfortable life for the most part, it was not always so. Traci Watson, writing for National Geographic in 2015, explains:

For ancient Egyptians, owning a menagerie of exotic animals conveyed power and wealth. But the remains of baboons, hippos, and other elite pets buried more than 5,000 years ago in a graveyard near the Nile reveal the dark side of being a status symbol. Baboon skeletons found at one tomb bear dozens of broken hand and foot bones, hinting at punishing beatings. At least two baboons have classic parry fractures, broken arms that typically occur when trying to shield the head from a blow. A hippo calf broke its leg trying to free itself from a tether and an antelope and a wild cow also show injuries probably related to being tied. (1)

Watson cites the scholar Wim Van Neer, of the Royal Beligain Institute of Natural Sciences, in concluding that Egyptians of earlier periods, who seem to have abused the animals in captivity, learned how to control them better in time. She writes that "mummified baboons from a later date show few signs of harsh treatment. Perhaps by then the ancient Egyptians had learned to keep animals without beating and tethering them" (2). Exotic animals were kept for any number of reasons and, among them, symbolic representations of power.

If a person kept a hippo as a pet, for example, they were "controlling a really chaotic force in nature" (Watson, 2). Crocodiles were kept for the same reason in certain temples as representatives of the god Sobek, the crocodile god. Sobek was considered a creator god in certain periods of Egyptian history and the sacred crocodiles in his temples were fed better than most humans of the time on choice cuts of meat and honey cakes. Crocodiles were mummified and preserved just as cats, dogs, monkeys, and other animals but the most potent animal preserved was the bull.

The Apis Bull

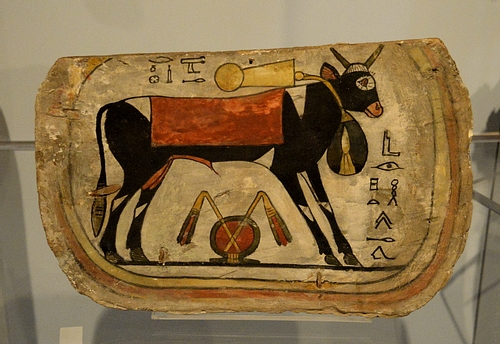

The bull was not a pet but a sacred animal who represented the god Ptah in the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150 - 2613 BCE). Historian Margaret Bunson writes:

Apis, the sacred bull, was a theophany of the Ptah-Sokar-Osiris cult at Memphis. The Palemro Stone and other records give an account of the festival honoring this animal. The ceremonies were normally called "the Running of Apis". The animal was also addressed as Hapi. The name 'Apis' is Greek for the Egyptian Hep or Hapi. The sacred bull of Apis was required to have a white crescent on one side of its body or a white triangle on its forehead, signifying its unique character and its acceptance by the gods. (27)

The Apis bull was so important that it was equated with the power of the king from the First Dynasty and probably earlier. The Narmer Palette shows a bull destroying a city as a symbol of the strength and virility of the king which is evidence that the bull as a symbol of might was already widely recognized prior to Narmer's reign of c. 3150 BCE. The Egyptologist Richard H. Wilkinson writes:

Apis was the most important of the bull deities of Egypt and can be traced back to the beginning of the Dynastic Period. The origins of the god called by the Egyptians Hap are not entirely clear, but because his cult center was at Memphis he was assimilated into the worship of the great memphite god Ptah at an early date - first as the 'herald' or son of that god, and eventually as the living image or manifestation of the 'glorious soul' of Ptah himself. ( 170)

The Apis bull was so important it was worshipped as early as the the First Dynasty (especially noted under the reigns of Narmer and Den) and as late as the Ptolemaic Dynasty (323 - 30 BCE), the last to rule Egypt before it was taken as a province of Rome.

Importance of Pets in the Afterlife

Whether they were exotic, deified, or domestic, pets played an important role in the lives of the ancient Egyptians. Scholar Bob Brier reports how, "in January 1906, Theodore Davis came upon a pit tomb that surprised him. The tomb lay at the bottom of a twelve-foot shaft cut into the bedrock" (cited in Nardo, 118). Brier reproduces the first hand report of Davis:

I went down the shaft and entered the chamber, which proved to be extremely hot and too low for comfort. I was startled by seeing very near me a yellow dog of ordinary size standing on his feet, his short tail curled over his back, and his eyes open. Within a few inches of his nose sat a monkey in quite perfect condition; for an instant I thought that they were alive, but I soon saw that they had been mummified, and that they had been unwrapped in ancient times by robbers. (Nardo, 118)

These animals were mummified pets but there were also animals mummified for food. Animals killed for food were usually fish or fowl and great care went into their preservation so that the deceased would have enough food in the afterlife. These mummies are not embalmed with the care that went into embalming a pet and are not wrapped with linens in the same way. Pet fish, for example, were very carefully tended while fish mummified for food were treated differently. Tombs throughout Egypt have been discovered containing mostly mummified pets.

One of the early excavators of Egyptian tombs, Belzoni (l. 1778 -1823) reported an enormous collection of mummified pets:

I must not omit that among these tombs we saw some which contained the mummies of animals intermixed with human bodies. There were bulls, cows, sheep, monkeys, foxes, bats, crocodiles, fishes, and birds in them; idols often occur; and one tomb was filled with nothing but cats, carefully folded in red and white linen, the head covered with a mask representing the cat and made of the same linen. (Nardo, 119)

The human experience was considered only one part of a person's eternal journey and, as such, the animals a person encountered in life were also to be expected in one's passage through death to eternity. There were dangerous animals in life, such as the crocodile and hippo, who would pose the same kind of dangers in the afterlife. There is one version of eternity which includes crocodiles which threaten and prevent one from reaching one's place in the Hall of Truth.

At the same time, those animals who had been one's trusted companions on earth could be counted upon to meet that person on the other side in the Field of Reeds. The ancient Egytians loved their pets just as people do in the present day. They recognized them as an integral part of their life on earth and understood that death was only a temporary separation and, one day, they would be reunited with their faithful friends again.