In the search for ever more impressive and lethal weapons to shock the enemy and bring total victory the armies of ancient Greece, Carthage, and even sometimes Rome turned to the elephant. Huge, exotic, and frightening the life out of an unprepared enemy they seemed the perfect weapon in an age where developments in warfare were very limited. Unfortunately, impressive though they must have seemed on the battlefield, the cost of acquiring, training, and transporting these creatures, along with their wild unpredictability in the heat of battle, meant that they were used only briefly and not particularly effectively in Mediterranean warfare.

Two Species of Elephant

In antiquity, two elephants were known – the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) and the African Forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis). The latter is now almost extinct and only found in the Gambia; it was smaller than the, at the time unknown, African elephant of central and southern Africa (Loxodonta africana), which explains why ancient writers all claimed the Indian elephant was larger than the African. The Asian elephant became known in Europe following the conquests of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BCE and contact with the Mauryan Empire of India. So impressed was Alexander with the war elephants of Porus, who was said to have had a corps of 200 when he fought the Battle of Hydaspes in 326 BCE, that he formed his own ceremonial elephant corps. Many of Alexander's successors went one step further and employed them in battle proper. Indeed, the Seleucid Empire made sure to exclusively control the traffic in Asian elephants.

Acquisition & Deployment

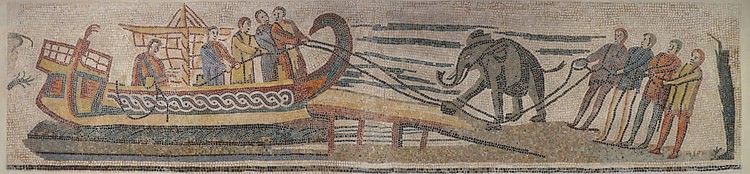

Elephants, being only available from Africa or Asia, were expensive commodities to acquire for Mediterranean powers. Added to this was the cost of maintaining them and training both the wild elephant and its rider to form some sort of battle order on the field of combat. Then there was the problem of transporting them to where they were needed, although famously, the Carthaginian general Hannibal managed to get at least some of his 37 elephants across the Alps and into Italy in 218 BCE.

Despite the cost and difficulties, and because in antiquity the evolution in weaponry was extremely slow, the attraction of such large animals trampling all over the enemy remained. This meant that military commanders went out of their way to supplement their armies with elephants. Seleukos I Nikator famously swapped parts of his eastern empire to gain 500 elephants from Indian emperor Chandragupta in 305 BCE. The armies of the Antigonids and Ptolemies also fielded Asian elephants, although generally in much smaller numbers. In the 270's BCE, for example, Ptolemy II trained African elephants for use in his army and even appointed a high official to be responsible for them, the elephantarchos. According to Plutarch, 475 elephants took part in the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE during the Successor Wars. In 275 BCE, in a battle known as the 'Elephant Victory', Antigonus Gonatas, although outnumbered, used 16 elephants to terrify an army of Gauls into retreat.

Pyrrhus of Epirus was the first commander to employ elephants in Europe when he used 20 Asian ones in his campaigns in Italy and Sicily from 280 to 275 BCE. There Pyrrhus gained notable victories against the Romans in the battles of Heraclea (280 BCE) and Asculum (279 BCE).

The Carthaginians were the next major users. Able to readily acquire African elephants from the Atlas forest region they formed an elephant corps from the 260's BCE. These were used in the First and Second Punic Wars against Rome in the mid and late 3rd century BCE, notably in the Battle at the river Tagus in Spain in 220 BCE and at the Battle of Trebia in northern Italy in 218 BCE. Elephants even appeared on Carthaginian coins of the period. After his initial corps died in the winter of 218/217 BCE Hannibal acquired fresh replacements and used elephants again at the siege of Capua in 211 BCE.

The Romans seem to have been largely unimpressed with the use of elephants and employed them only rarely and in small numbers, usually supplied via Numidia. They were said to have cunningly released pigs to disrupt Pyrrhus' elephants at the Battle of Maleventum in 275 BCE. Even more famously, at the Battle of Zuma in 202 BCE, the Roman general Scipio Africanus allowed Hannibal's 80 elephants to run through gaps purposely made in his infantry lines and then turned the animals around using drums and trumpets to let them cause havoc with the enemy. Nor were elephants any help to the senatorial armies of Scipio and Cato that faced Julius Caesar in North Africa at the Battle of Thapsus in 46 BCE. Elephants were, perhaps strangely, not used by the Romans as transportation of heavy goods either.

There is a curious instance when two elephant corps met where each side was composed of different types. This was at the Battle of Raphia (on the Sinai peninsula) in 217 BCE between Ptolemy IV and Antiochus III. The former had 73 African elephants against the latter's 102 Asian elephants. The two elephant corps clashed directly and the smaller-sized African elephants gave way, even if Ptolemy won the battle overall. After a few centuries when elephants were out of vogue, the Sasanians in Persia revived the use of war elephants, fielding the Indian species from the 3rd century CE onwards, albeit, largely for logistics and during sieges.

Armour & Battlefield Strategies

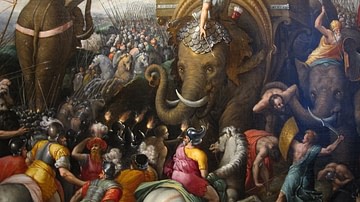

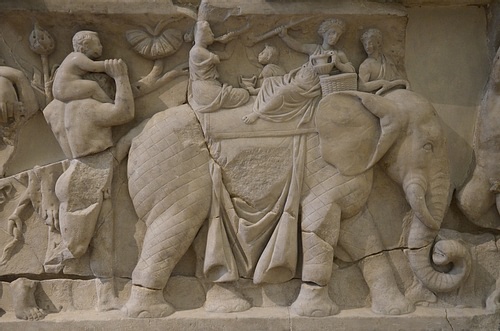

Elephants were dressed for battle in armour which protected their heads and sometimes front. A thick sacking or leather cover could also be hung over the elephant's back to protect its sides. Sword blades or iron points were added to the tusks and bells hung from the body to create as much noise as possible. Early use of elephants in battle by Alexander's successors involved only a rider (mahout) and perhaps a spearman. The rider was crucial as he had trained the animal for years and it would obey only his commands. He controlled the direction the elephant took by applying pressure behinds the animal's ears with his toes. He also had an ankush or hooked stick for this purpose.

From the 270's a light-weight tower (howdah or thorakia) of wood and leather was strapped to the larger Asian elephant using chains, and protected with shields hanging down its sides. It was typically occupied by up to four javelin or missile throwers. However, it was the elephant itself that was the principal weapon, employed as a sort of mobile wrecking ball. At an average height of 2.5 metres, weighing around 5 tonnes, and trotting up to 16 km/h (10mph), they could be tremendously effective wrecking machines. As the ancient historian Ammianus Marcellinus put it, "the human mind can conceive nothing more terrible than their noise and huge bodies" (Anglim, 132).

The most important effect of elephants in the field was probably, then, a psychological one. These huge beasts would have terrified men and horses both visually and orally with their trumpeting. Even the smell of elephants could drive unprepared horses into a stampede. Starting the battle in a simple line in front of their own troops they could cause undisciplined and poorly trained cavalry lines to scatter in panic. They were also used to combat any elephants in the opposition's ranks. Tossing, ripping, and crushing the enemy, elephants were used to cause havoc with any defensive fieldworks and fortifications too, where they knocked down walls with their foreheads or pulled them down with their trunks.

Elephant corps did not have everything their own way, of course. Firstly, both soldiers and cavalry horses were trained to get used to the sight, smell, and sounds of elephants. Then they obviously provided large targets for artillery fire. Pits and spikes were prepared to entrap them and, if they could get close enough, men were charged with hamstringing the beasts or hacking at their trunks. This latter eventuality was, in part, avoided by the stationing of a small team of infantry to protect the elephant's legs. If the elephant were wounded then all hell might break lose as, unpredictable at the best of times, wounded elephants could literally go mad and cause tremendous damage to both sides. If this happened the rider used a metal spike and hammer to pierce the elephant's brain and kill it immediately.

Conclusion

Once the devastating sight of war elephants became a more common one on the ancient battlefield so their effectiveness diminished as the enemy became more prepared and better equipped to deal with them. In reality, perhaps only a handful of ancient battles had been decided because of the intervention of elephants. This was especially so as Roman warfare developed. Troops became more mobiIe, siege-craft became just as common as open battles, and artillery came to the fore. In later times, the use of elephants was restricted to peace-time activities such as spectacles in the Roman arenas and circuses for public entertainment or as an impressive addition to public processions. Indeed, such was the demand that at Latium and Constantinople permanent herds were kept and the insatiable desire for wild elephants practically wiped out the forest elephant of North Africa. During the late Roman Empire elephants were also given and received as gifts to improve diplomatic relations with neighbouring states.