The 390 BCE battle at the Allia River was fought between the city state of Rome and Gauls from northern Italy. When the Gauls laid siege to the Etruscan city of Clusium, the Romans intervened on behalf of the latter. The Gauls withdrew but returned to advance on Rome itself. Close to Rome, at the Allia River, the Roman army met the Gauls in battle but suffered a crushing defeat.

PROLOGUE

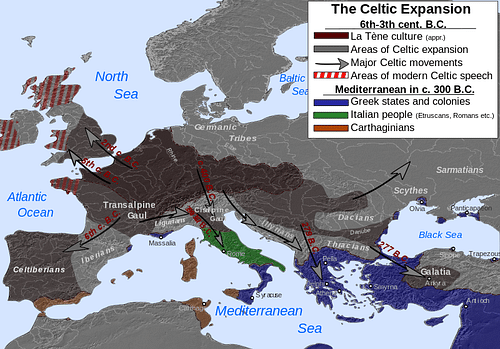

Between 1000-500 BCE, the gradual expansion of Celtic tribes from central Europe transformed most of Western Europe into a Celtic world. Enticed by the riches of the Mediterranean lands, tribes of Celts wandered into the north Italian plain where they became known as Gauls or Gallic tribes. After 400 BCE the Gauls began to take the lands they desired by force, conquering the mosaic of cultures that lived in the Po River valley.

In 391, Brennus, chief of the Senones, led a Gallic army south into Etruria, where he besieged the town of Clusium. Clusium was part of the Etruscan civilization which flourished to the north of the powerful city-state of Rome. The Etruscans were politically divided, however, and with no help forthcoming from the other Etruscan cities, Clusium appealed to Rome for help. Rome then sent the Fabii, the sons of the influential patrician Fabius Ambustus, as envoys to Clusium.

The Fabii asked the Gauls, what gave them the right to invade Etruscan lands. The Gauls answered “that they carried their right in their weapons” (Livy, The History of Rome, 5. 36). Putting the Gauls' words to the test, the Fabii led the Clusians in a sally out of the city. Brennus was flabbergasted to see one of the Fabii kill a Gallic chieftain; shockingly, an ambassador had broken the peace. Unsure on how to deal with the Roman aggression, Brennus pulled his army back to his Senones homelands.

The Gallic chiefs held councils to figure how to deal with the Romans. Their pride stung and it was, no doubt, mostly the younger nobles who called for war. However, it was the cooler heads of the elders that prevailed. Gallic ambassadors were sent to Rome, where they petitioned the Senate to hand over the Fabii to the Gauls. Although both the Senate and the Fatiales (the priestly guardians of peace) were sympathetic to the Gauls, the father of the Fabii had more influence. Not only did the Fabii not surrender, they were elected as consular tribunes and as such given command of the army. Insulted, the Gallic envoys threatened war and departed.

THE ARMIES FACE EACH OTHER

Winter had passed while the negotiations were going on. In the spring of 390, warnings arrived at Rome from Clusium that a large army of Gauls led by Brennus was rapidly moving towards Rome. The Gauls for the most part spared the countryside of Rome's neighbors, exclaiming that their goal was Rome. The Romans remained unworried, feeling that their legionaries were more than a match for any number of culturally inferior 'barbarians.' On July 18, the Roman army met the Gauls eleven miles from Rome. The Gauls were on the left bank of the Tiber River, close to its confluence with the smaller Allia River. The Allia was behind the Gauls, with hills to their left and the meandering Tiber to their right.

The backbone of the 15,000-men-strong Roman army was the legion. The 6000 Roman citizens of the legion fought as a phalanx of hoplites, a tactic that was widely used in Greece and Etruria. The hoplites were heavy infantry; armored with helmet, breastplate, greaves and a bronze round shield. Their weapons were the thrusting spear and the sword. The phalanx of shields and armored warriors, bristling with spears, presented an image of unyielding strength. In addition to the legion there were Roman light troops and 600 cavalry as well as soldiers from allied settlements.

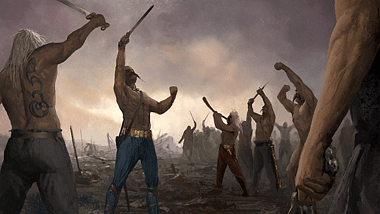

Well over 30,000 Gauls faced the Romans. Nearly all the Gauls were light infantry, protected only by a yard-long oblong shield and perhaps a helmet. The latter was decorated with horns, crests of animal designs or the Celtic symbol of war, the wheel. Only the Gallic nobles could afford mail shirts or round breastplates. They arrived in chariots but would fight on foot or on horseback. The Gauls wielded swords, spears, axes, javelins or slings. With their hair swept back like the mane of a horse and with their droopy mustaches, baring their upper body or stripping completely naked, shouting and waving their weapons about, the tall Gallic warriors were a fearsome spectacle.

The great numbers of Gauls enabled Brennus to extend the front of his army far beyond that of the Romans. Trying to match the width of the Gallic front, the Romans took men from their center to extend their own lines. Even then the Gallic army continued to extend beyond the Roman front, and worse, now the Roman ranks had become dangerously thin. The Romans stationed their poorly armed and inexperienced reserves on a small hill on their right flank.

THE BATTLE

Brennus feared that the Roman reserves would outflank his left wing and strike at his army from the rear. To avoid this danger, Brennus opened the battle by having his best warriors, probably his cavalry, assault the Roman reserves. Holding the higher ground, the Roman reserves persevered for a while until the brute power of the Gauls threw them into disarray.

The panic on the hill spread from those nearest to the reserves, all the way across Roman the lines. At this moment, with trumpets and horns blaring, the whole Gallic army charged. The ferocity and momentum of the barbarians completely shattered the Roman phalanx. The Gauls could scarcely believe their good fortune. “None [of the Romans] were slain while actually fighting; they were cut down from behind whilst hindering one another's flight in a confused, struggling mass” (Livy, The History of Rome, 5.38). The left wing of the Roman army and most of its center were swept toward the Tiber. Along the banks, the Gauls hewed down their panicked enemy. Trying to escape the carnage, many Romans dove into the river but those too exhausted or wounded were pulled under by the current.

The Romans that made it across the Tiber, gathered at the deserted Etruscan ruins of Veii. On the Roman right wing too, many escaped into the hills from where they fled to Rome. The Gauls could not believe the ease of their victory. Piles of enemy weapons were offered to their gods. Grizzly trophies, decapitated enemy heads, were tied to spears, chariots and to the harnesses of horses.

THE AFTERMATH

Perhaps less than a third of the Roman army survived its defeat at the Allia. The Gauls lost barely any of their men. Nothing stood in their way. Three days later, the Gauls entered the undefended gates of Rome and sacked the city. On the Capitol Hill a group of Romans held out against a prolonged Gallic siege. Their own ranks decimated through disease, the Gauls finally withdrew after being paid a hefty ransom.

The defeat at the Allia and the sack of their city had a profound effect on the Roman military. General Marcus Furius Camillus, conqueror of Veii and resistance leader against the Gauls, initiated a series of military reforms that were further refined during the Samnite Wars of the late 4th century BCE. The unwieldy phalanx was replaced by the more elastic 60-120-men-strong maniple, which could independently move back and forth without messing up the whole battle line. Volleys of javelins were followed by combat with the short sword. The round shield was replaced by the more familiar Samnite scumtum, a large semi-cylindrical and four-cornered shield.

Politically, the Roman defeat on the River Allia, caused erstwhile allies to waver and former enemies among the Aequi, Volsci and Etruscans to reopen old wars. What was won in over a hundred years was lost in a single battle. As for the Gauls, for most of the 4th century, they were kept busy consolidating their hold over the north Italian plain, avoiding major conflicts with Rome until the beginning of the 3rd century BCE.