The first tunnels in the Mediterranean were built to transport water from distant springs and mountains to arid areas and cities. They also ensured the constant supply of water when cities were under siege. For example, the 533 m (583 yards) Hezekiah tunnel built in the late 8th and early 7th century BCE took water from the Gihon spring to the city of Jerusalem and was built as the city was preparing for an impending siege by the Assyrians. The Romans adopted the construction techniques of other civilizations to build a large number of tunnels in the territories that they controlled in Europe, North Africa and Asia Minor. They built tunnels to transport water, to divert rivers, to drain lakes for the irrigation of agricultural lands, and for their road projects and mining operations.

Persian Tunnels

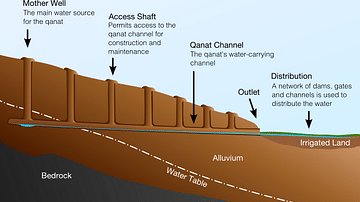

The Persians were one of the first civilizations to build tunnels that provided a reliable supply of water to human settlements in arid areas. In the early first millennium BCE, they introduced the qanat method of tunnel construction which consisted in placing posts over a hill in a straight line and digging vertical shafts at regular intervals. Underground tunnels were excavated between the shafts which ensured that the tunnel did not deviate from its set trajectory. The shafts also provided ventilation to the workers below and were used to take the excavated spoil to the surface using leather bags or baskets lifted by winches. Remarkably, some qanats built by the Persians 2,700 years ago such as the one in the city of Gonabad, Iran are still in use today.

Roman Qanat Tunnels

The Etruscans adopted the qanat technique in the 6th century BCE to build a large number of water-supply tunnels called cuniculi in the northeast of Rome. They later passed on their know-how to the Romans who also used the qanat method to construct aqueducts. Vitruvius in his On Architecture describes how Roman qanat tunnels were constructed with vertical shafts (called puteus or lumen) dug at 35.5 m (115 ft) intervals, even though in reality intervals could vary between 30 m (98 ft) to 60 m (197 ft). The shafts were equipped with handholds and footholds and were covered with wooden or stone lids. To ensure that the shafts were vertical, Romans hung plumb-bob lines from a rod across the top and made sure that the bob ended in the center down the shaft. Plumb bob lines were also used to measure the depth of the shaft and to determine the slope of the tunnel with precision. Qanat tunnels were similarly built to divert rivers and drain lakes for agriculture and/or to regulate water levels. For example, Emperor Claudius built the 5.6 km (3.5 miles) long Claudius tunnel in 41 CE to drain the Fucine Lake (Lacus Fucinus). This tunnel had shafts that were up to 122 m deep, took 11 years to build and used approximately 30,000 workers.

Counter-Excavation Tunnels

By the 6th century BCE, a second method of tunnel construction appeared called the counter-excavation method in which the tunnel was excavated from both ends. It was used to perforate high mountains when the qanat method was not a viable alternative. This method required greater planning and advanced knowledge of surveying, mathematics and geometry as both ends of a tunnel had to meet correctly at the center of the mountain. Adjustments to the direction of the tunnel also had to be made whenever builders encountered geological problems. Builders had to constantly check the tunnel's advancing direction, for example, by looking back at the light that penetrated through the tunnel mouth, and had to make corrections whenever the tunnel deviated from its set trajectory. Large deviations could happen and errors could either be altimetric or planimetric. Altimetric errors were errors related to altitude or to the vertical direction of the tunnel while planimetric errors were horizontal errors. Altimetric errors were the most serious as they could result in one end of the tunnel not being usable.

The Saldae aqueduct system (in modern day Bejaia, Algeria) built by the Romans in circa 150 CE and consisting of a 300 m (984 ft) bridge and a 428 m (1,404 ft) tunnel is known for an inscription on a three-sided semi-column written by the surveyor Nonius Datus. The inscription provides unique technical details about the construction of the tunnel of Saldae and the problems faced by the builders. Nonius Daus describes how the two teams of builders missed each other in the mountain and how the later construction of a lateral link between the two galleries corrected the initial error. In this instance, the error was planimetric and could be rectified.

Road & Mine Tunnels

Romans also dug tunnels for their roads whenever they encountered topographical obstacles such as hills or mountains, too high for roads to pass over them. An example is the 37 m (121 ft) long and 6 m (20 ft) high Furlo Pass tunnel (Passo del Furlo) built by emperor Vespasian in 69-79 CE which was built for the Via Flaminia using the counter excavation method. Remarkably, a modern road still uses this tunnel today. The longest known Roman road tunnel is the 1 km (0.6 miles) long Cocceius tunnel (Grotta di Cocceio) near Naples built in 38-36 BCE using the counter excavation method. The Cocceius tunnel also had shafts which provided ventilation. It connected Lake Avernus with the city of Cumae and was built as Lake Avernus was in the process of being converted into a military port, the Portus Iulius. The tunnel was decorated with a beautiful colonnade and many statues set in niches on its Avernus side.

Tunnels were also built for mineral extraction, especially gold. Miners would locate a mineral vein and then pursue it with shafts and tunnels underground. Traces of such tunnels can still be found at the Dolaucothi gold mines in Wales. When the sole purpose of a tunnel was mineral extraction, construction required less planning as the trajectory of the tunnel was determined by the mineral vein.

Construction Time

Roman tunnel projects were usually planned by a military librator (surveyor) and built by military personnel often helped by a number of slaves. The length of construction of the tunnel depended on the method being used and the type of rock being excavated. The qanat construction method was usually faster than the counter-excavation as it was more straightforward and because the mountain could be excavated not only from the tunnel mouths but also from shafts. Lack of ventilation, especially for long tunnels without shafts, was also an issue, and made construction work exhausting for tunnel workers. The type of rock could also influence construction times. When the rock was hard, Romans employed a technique called fire-quenching which consisted of heating the rock with fire, and then suddenly cooling it with cold water so that it would crack. Progress through hard rock could be very slow and it was not uncommon for tunnels to take years if not decades to be built. Construction marks left on a Roman tunnel in Bologna shows us that the rate of advance through solid rock was 30 cm (12 inches) per day. In constrast, the rate of advance of the Claudius tunnel can be calculated at 1.4 m (55 inches) per day.

Maintenance

Tunnels had to be regularly maintained as debris accumulated or as leaks developed over the years. Leaks were dangerous as they could lead to the subsequent collapse of the tunnel. Maintenance workers used the shafts, when they existed, to reach the tunnel and do maintenance work. Shafts could also be used to release air pressure in water tunnels during periods when the flow of water increased dramatically. Most tunnels had inscriptions showing the name of patrons who ordered construction and sometimes the name of the surveyor or architect. For example, the 1.4 km (0.87 miles) Çevlik tunnel in Turkey, built to divert the floodwaters threatening the harbor of the ancient city of Seleuceia Pieria, had inscriptions on the entrance, still visible today, that indicate that the tunnel was started in 69 CE under Vespasian and was completed by Titus in 81 CE.

Conclusion

Just as with other large construction projects, tunnels were a way for emperors to not only show their benevolence but also to project their power throughout the empire. Tunnels were built in the territories that Rome controlled in Europe, North Africa and Asia Minor in order to transport water, to irrigate agricultural lands, for roads and for mining activities. The Romans adopted the qanat construction method invented by the Persians and by the 6th century BCE they also mastered the counter-excavation method to pierce through high mountains. Tunnels could take years to be built and needed to be regularly maintained. Even though they are not as visible as other large ancient construction projects, be they aqueducts, bridges or viaducts, Roman tunnels truly are engineering marvels and a testament to the Romans' great engineering skills.