The Middle Kingdom of ancient Egypt (2000 BCE – 1700 BCE) saw the start of more formal writing which included religious scripts, administrative notes, and more in-depth fictional writing. One of the most iconic pieces of writing to come out of the Middle Kingdom was The Tale of Sinuhe. Sinuhe was a courier and assistant to the King of Egypt, Amenhotep I. He fled Egypt and joined a Bedouin tribe to the east and started a new life near Syria. Once he reached old age he returned and finished out his life in Egypt. The importance of this story goes beyond the structure and writing techniques of the text as it provides insight into the cultural differences between Egypt and the Near East. Philologists are still analysing the text and acquiring new insight into the text today. This 4,000-year-old tale provides insight into the world and mind of an Egyptian and is just another example of Egyptian brilliance.

Berlin 3022 & 10499 Papyri

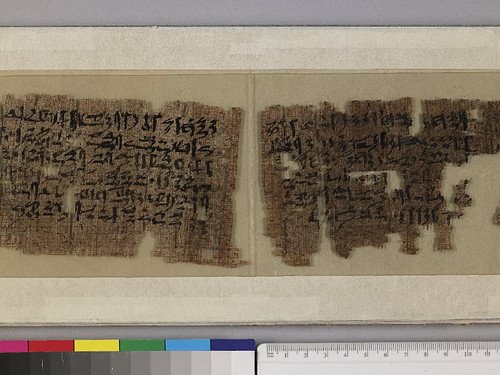

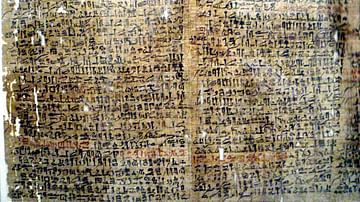

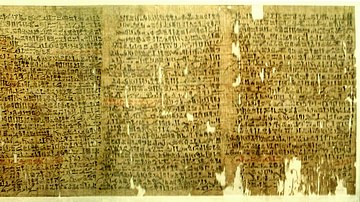

The best-known copies of Sinuhe were from the 12th and 13th dynasties (1900-1700 BCE), and these manuscripts are labelled Berlin 3022 and 10499. The Berlin 10499 (Also known as Ramesseum papyrus 10499) has The Tale of Sinuhe and another story called The Tale of the Eloquent Peasant on the reverse side of the papyrus. Berlin 3022 is the most well-preserved and the best account for translation. The Berlin 3022 is missing the beginning of the tale with 311 total lines, and Berlin 10499 has the beginning, but only has 203 lines. Egyptologists today discuss the strategy of the scribe who created these papyri. They have created a modern replica of the papyrus roll which is five meters long and cut into fourteen sections. When we closely analyse the script we can observe the scribes attempt to clean off the papyri from previous writing and debris. The total word count in most English translations is 4,500 words.

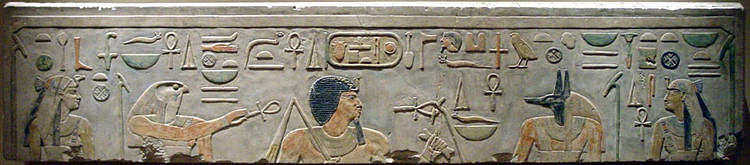

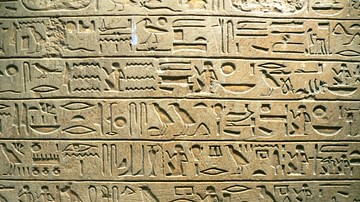

The text on the papyrus is known as Hieratic. This form of writing is like cursive for Middle Egyptian hieroglyphs. This is not to say that Middle Egyptian Hieroglyph versions do not exist. Hieratic was a simpler and faster method for writing larger works of literature, administrative, and religious texts. Schools for scribes used this story as a model for practice, which created many incomplete copies of the story. The Berlin examples are of papyri, but the copies created by students who were training to be scribes used ostraca or limestone flakes. The story is one of the first forms of autobiographical storytelling and, although the author of the story is unknown, he is considered to be the Shakespeare of Middle Egypt. Egyptologists find this tale to be one of the finest pieces of literature to survive from Ancient Egypt. We see many examples in museums like the Berlin Museum, British Museum, and the Ashmolean Museum.

Transliteration from Middle Egyptian to English

nn pDty smA m idHy There is no desert-nomad who befriends a marshman

ptr smn idyt m Dw Does a marsh-reed flourish on the mountain-side

in iw kA mr.f aHA Does a bull love to fight,

pry mr.f wHm sA m Hr nt mxA.f sw Then should a herd-leader like to turn back in fear of being matched?

ir wnn ib.f r aHA imi Dd n.f xrt-ib.f If he wishes to fight, let him be told his wish in

iw nTr xm Sat.n.f rx nt pw mi-m” Does a god not know what he ordained? Or a man who knows how it will be?”

sDr.n.i qAs.n.i pDt.i wd.n.i aHAw.i I went to rest, tied my bow, sharpened my arrows,

an.i sn n bAgsw.i sXkr.n.i xaw.i Whetted the blade of my dagger, arrayed my weapons

HD.n tA rtnw iyt Ddb.n.s wHyt.s At dawn Syria came, it roused its people,

A Summary of The Tale of Sinuhe

The story of Sinuhe refers to a man who fled his duties in Egypt and became a Bedouin in an Asiatic tribe. Sinuhe was an assistant to King Amenemhat I who was the first king of the 12th Dynasty in Egypt (1991-1962 BCE). The tale begins with the death of Amenemhat and the news travels to his son Senusret I who is fighting in the East. Word of his death reaches the son and Sinuhe. Sinuhe panics and is scared to return home as he is unaware of how the King died. He then flees to the east to go into exile.

For further reading on the death of Amenemhat I, read The Testament of Amenemhat. The story provides implications for the death of Amenemhat, and his ghost finds his son Senusret and helps aid his son through his reign. The story provides insight into remarkable Egyptian poetry and the views of the afterlife. Another quick note of interest is the names of leaders may differ depending on the translation. Amenhotep I is also described as Sehetepibra by some translations, and Senusret I may also be described as Sesostris I or Kheperkara. The names vary due to individual preference and what document is being used for translation.

During the early years of Sinuhe's exile, he runs into a man who is a leader of an Asiatic tribe called the Renetu. He is taken in and Sinuhe marries the leader's eldest daughter and becomes a leader of his own tribe within the Renetu. After being chosen as a commander of the military, he completed the tasks set before him by the leader. These included battles, taking livestock, and taking prisoners. Sinuhe had multiple children and raised them into adulthood. As he aged he began to long to go back home to Egypt.

One fateful night, Sinuhe was confronted by a warrior who was sent to kill him. The now older Sinuhe accepted the challenge and duelled with the man. After a hard-fought battle, Sinuhe was victorious. He killed the warrior and began to think back on his life. He missed Egypt more than ever and wanted to finish out his life back in his old home. Fortunately, soon thereafter Sinuhe received a letter from the King of Egypt, Senusret I. The letter requests him to return to Egypt and meet with the king. Sinuhe was excited, yet wary as he fled after the death of Amenemhet I. After Sinuhe agrees to meet with the king, he leaves his wife and children behind. He makes his eldest son the new leader of the tribe.

Sinuhe returns to Egypt and walks through the capital and meets with the king. The king was pleased to see him and gave him a place to sleep and to clean up. As a Bedouin, Sinuhe had tattered clothes, long hair, and a beard. This look was not acceptable in Egypt as royalty and the upper elites were clean-shaven men. The king forgave Sinuhe for fleeing his post and gave him the opportunity to become a part of the Egyptian elite. Sinuhe lives out his life in Egypt and is buried in a tomb for the elite class.

Today, scholars are still not sure whether or not Sinuhe is a real individual. The tale was to represent the adventures of the courier Sinuhe copied from the inscriptions from his tomb. The rulers and locations described were authentic and the cultural differences described were also accurate. Regardless, the tale is one of the oldest forms of fictional storytelling. The story was written nearly 4,000 years ago, and interpretations are still created in the modern day. A 20th-century CE Finnish writer Mika Waltari wrote a novel called Sinuhe Egyptiläinen which has been translated by Naomi Walford.