The Hoysala era (1026 CE – 1343 CE) was marked by illustrious achievements in art, architecture, and culture. The nucleus of this activity lay in the present day Hassan district of Karnataka, India. The most remarkable accomplishment of this era lies, undoubtedly, in the field of architecture. The intention of surpassing the Western Chalukyan Empire (973 CE – 1189 CE) in its own sphere provided further impetus for excelling in the field of architecture.

History of the Hoysala Empire

The Hoysala rulers began as local chieftains in the hills of Western Ghats. With time, their fortune began to prosper and within a few decades they achieved the status of a powerful feudatory under Western Chalukyan Emperors. Early in the history of Hoysala dynasty, the capital of their nascent dominion was shifted from the hills of Western Ghats to Belur. The military conquests of Vishnuvardhan (1108 CE – 1152 CE) against the neighbouring Chola Empire (c. 300 BCE – 1279 CE) in 1116 CE marks the first major development in the history of these dynasts. A new age now ushered with Vishnuvardhan as he built the Chennakesava temple (1117 CE) in Belur to celebrate this victory; furthermore, he decided to shift the capital almost 20 km to the east to Halebidu or Halebid.

The Hoysalas gained their political freedom in 1192 during the reign of Veera Ballala II (1173 CE – 1220 CE). They soon became a leading power in Southern India and enjoyed territorial supremacy and economic well-being over the next century or so. At its height, the empire consisted of present day Karnataka, parts of Tamil Nadu and south-western Telangana. However, invasions of sultanates from Delhi and Madurai, from 1311 CE onwards, proved fatal to the then reigning monarch, Veera Ballala III (1292 CE – 1343 CE). He eventually succumbed to these repeated onslaughts in 1343 CE.

Nature & Influence

The Nolamaba (late 8th – 11th century) and Western Ganga (350 CE – 1000 CE) dynasties – predecessors of Hoysalas in Southern Karnataka – constructed both Hindu and Jain temples inspired by Tamil heritage. In contrast, the Hoysala rulers were influenced by the Western Chalukyan architecture and employed their craftsmen as well.

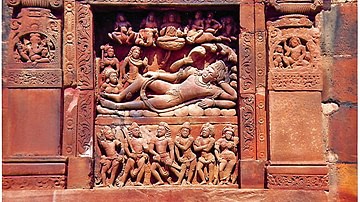

An abundance of figure sculpture covers almost all the Hoysala temples. Soapstone, which allows fine detailing and clarity, also helped in this predilection. This is a return to a more extensive iconographic representation of episodes from popular epics compared to later Western Chalukyan architecture. It must be remembered, however, that in temple architecture these do not merely serve a decorative purpose, but are essential to the integrity and composition of the structure.

Brief Introduction to Temple Architecture

A cuboid cell, the garbha griha (sanctum sanctorum) houses a centrally placed murti (enshrined icon) on a pitha (pedestal). The shikhara (superstructure), rises over the garbha griha and together with the sanctum they form the vimana (or mulaprasada) of a temple. A ribbed stone, amalaka, is placed atop the shikhara with a kalash at its finial. An intermediate antarala (vestibule) joins the garbha griha to an expansive pillared mandapa (porch) in front, chiefly facing east (or north). The temple may be approached via entrances with gigantic gopurams (ornate entrance towers) towering over each doorway. In the prakaram (temple courtyard) several minor shrines and outbuildings often abound.

The vimanas are either stellate, semi–stellate or orthogonal in plan. The intricately carved banded plinths, a distinguishing characteristic of the Hoysala temples, comprise a series of horizontal courses that run as rectangular strips with narrow recesses between them. Also, the temples themselves are sometimes built on a raised platform or jagati which is used for the purpose of a pradakshinapatha (circumambulation).

To study in detail the architecture of the period, we will consider examples from Belur and Halebidu which together contain some of the finest surviving temples from that era.

Belur

Chennakesava Temple Complex

This is an ekakuta, i.e., a temple with one shrine. Regrettably, the shikhara has been lost to the ravages of time. The garbha griha houses an enshrined image of Krishna (Chenna means beautiful whereas Kesava is another name of Krishna). The whole temple, built on a grand scale, follows the general pattern of Hoysala architecture. It has an east–west orientation set on a jagati. The hall has 60 bays and a shrine measuring 10 m on either side. Under the eave cornice of mandapa (outdoor ritual hall) there are 38 most wonderfully sculpted figures called salabhanjika or madanika (bracket figures). Their placements and inscriptions reveal these to be later additions (primarily during the reign of Veer Ballala II).

To the southern end of this main temple lies Kappechennigaraya, consecrated by the queen of Vishnuvardhan, Shantala, the same year. Beside the main shrine there is a subshrine housing the image of Venugopal. This temple follows the stellate plan but is less ornamental.

The same compound houses another temple named Viranarayan to the west of Chennakesava. It is an ekakuta, Vaishnava temple, probably erected at a later date of the 12th century CE. It is built following the basic pattern of a garbha griha and an antarala opening up to the mandapa, all built on jagati. Interestingly, this temple is relatively austere, lacking in the narrative friezes that are abound in Chennakesava temple.

A relatively minor structure, the Saumyanayaka temple is situated to the southwest of the main temple. Its damaged shikhara was repaired in 1387 CE by a minister under the Vijaynagar King Harihara II.

A stepped pond called Vasudev Tirtha was constructed to the northwest of Chennakesava by Veer Ballala II. It is a consistent feature of any temple in which devotees perform an ablation before entering the mandapa.

Many such additions and modifications, both minor and significant, have been carried out well into the reign of later day monarchs of this region.

Halebidu

Originally Halebidu was called Dwarasamudra which refers to a large water reservoir that was excavated almost three-quarters of a century before the city being selected as the capital of the Hoysala Empire. Its present name means 'old city', doubtlessly indicating to the fact of its abandonment after being ransacked twice by the invading armies of the sultanates.

Hoysaleshwara & Shantaleshwara

In this dvikuta (temple with two shrines) Shaiva temple, the two garbha grihas (sanctum sanctorum) are found connected by a mandapa (porch) forming a large open hall. One shrine is dedicated to King Vishnuvardhan and the other to his Queen Shantala, therefore it is called Shantaleshwara. Built in 1121 CE, it was principally constructed under the patronage of wealthy local merchants and aristocrats. There are four entrances to the twin temple with miniature vimanas flanking them on either side. Two adjunct shrines, one for Nandi (bull) and another for Surya (sun) are also built on the same jagati. The exquisite friezes on temple walls eloquently render stories from Ramayana, Mahabharata and Bhagavata Purana. These reliefs preserve one of the finest achievements of Hoysala craftsmen and constitute an exhaustive lesson in the symbology of Hindu art.

Kedareshwara

This Shaiva trikuta (temple with three shrines) temple is located only a couple of kilometers to the south of Hoysaleshwara. It was built under the patronage of King Veer Ballala II and Queen Ketala Devi. Designed following a stellate plan, the central shrine is connected to the other two laterally positioned shrines by a common mandapa. The sculptural details illustrate beautifully executed Bhairava, Vishnu as Bharadwaj and Kaliyadamana among others.

Kalyani Tank, Hulikere

In the suburb of Halebidu, present day Hulikere, this splendidly decorated tank was built for a Shaiva temple during the reign of emperor Narasimha I (1152 CE – 1173 CE). Ironically, no trace of the temple could be found today, but this tank still survives. This stepped pond is adorned with 27 miniature shrines, some even carrying a superstructure atop.

Jain Temples in Bastihalli

Further south from Kedareshwara, in the village of Bastihalli, lies a group of three Jain temples. These temples are dedicated to Jain tirthankars (teaching gods) Adinath, Parsvanath and Shantinatha. Each temple enshrines an image of the respective tirthankar in their garbha griha. Parsvanath Basti was built in 1133 CE by King Vishnuvardhan to celebrate the birth of his son, Narasimha I. Aligned along the north-south axis, all of these structures faithfully follow the general architectural pattern of the Hoysalas.

Of these, the Adinath Basti, built in the late 12th century CE, is the smallest in size. It carries a beautifully decorated image of Saraswati inside its vestibule. This place seems to have for long been a sacred spot for Jains as archaeological remains dating back to the mid-10th century CE are found.

The twin cities of Belur and Halebidu were once the crown jewels of Hoysala Empire. Today they attract a most well-deserved attention from tourists, scholars, and devotees alike from different parts of the country and world at large. Daily worships continue in most of the shrines even today. Despite the irreparable losses suffered at the hands of time and mercenary human forces, the grandeur of these structures and piety that went into their construction continue to inspire reverence from the silent beholder to this day.