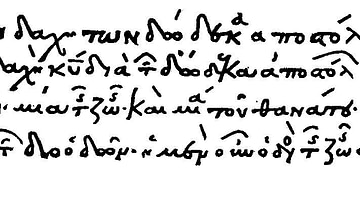

During the early years of Christianity, many of the church leaders or "Fathers" wrote down admonishments and instruction on what it meant to be a follower of Jesus as well as what liturgical ceremonies should be followed as a believer in these early Christian communities. One of these apostolic fathers, whose identity is unknown, wrote such a document entitled, The Teaching of the (Twelve) Apostles, or as it is commonly referred to today—The Didache.

This document, composed sometime between 70 and 150 CE in Syria or Egypt, presents to its readers a message of instruction regarding liturgy, personal behavior, and eschatological application and belief. The liturgical or common ceremonial practices of the church are thoroughly detailed in this document as are the admonishments towards individual holiness in specific and common circumstances. In the end, The Didache eventually synthesizes these two factors (public manner versus personal integrity) and shows their connection and grand purposes.

Significance

The influence and importance of this document to its original readers and even to modern-day Christian believers is impressive. The Didache presents a clear and concise advice on dealing with the pragmatic constructs of the Christian church. However, it still cleverly and successfully melds the functionality of Christianity with its spiritual side. Johannes Quasten, in his Patrology series states, "Scholars, constantly drawn to its precious contents, have gained repeated inspiration and enlightenment from this little book" (30). Kurt Niederwimmer, in The Didache: A Commentary on the Didache writes, "The whole composition is unpretentious as literature, nourished by praxis and intended for immediate application" (3). Furthermore, in The Apostolic Fathers, it proclaims that the Didache is "one of the most fascinating yet perplexing documents to emerge from the early church" (Lightfoot and Harmer, 145).

Thus, the importance of The Didache should not be dismissed merely because of its size or exclusion from the Scriptures. Like many other theological works written at the time, its usage was at times questioned, and a general opinion of it emerged as it being non–canonical. Theologian and monk Tyrannius Rufinus (340–410 CE) specifically makes reference to The Didache and said that it would have been "read in the Churches, but not appealed to for the confirmation of doctrine" (Schaff, 558). Athanasius of Alexandria (296–373 CE) states that this document was "appointed by the Fathers to be read by those who newly join us, and who wish for instruction in the word of godliness" (Schaff, 552). Eusebius Pamphilus, in his Ecclesiastical History, also speaks of The Didache as not being in the Canon of scripture. As such, it provides to the modern-day reader an understanding of the influence this work had on the early church despite its lack of canonical authority. It also shows that Christianity, like the Jewish faith, had its own unique ceremonies of religious value.

Liturgical Aspects

The Didache provides direction on the public worship in the church and furnishes to its reader clear examples of how certain ceremonial activities are to be handled. For instance, its 4th chapter refers to daily prayer and states, "In church you shall confess your transgressions, and you shall not approach your prayer with an evil conscience" (Lightfoot and Harmer, 152). This gives to the reader a pragmatic but still personal call to prayer. Communication with God is important, but a pure heart is quintessential. Later on in its 8th chapter, the reader is urged to pray three times a day as Jesus did in Matthew 6:9-13. Again, this prayer should come from a clean heart free from hypocrisy.

Chapter 9 of The Didache offers three different prayers to be used specifically during the Eucharist (or Holy Communion as it is referred to today). One prayer is for celebrating the cup of wine which is Christ's blood, one is for celebrating the bread, which is Christ's body, and the last is a prayer of thankfulness for knowledge of Christ and for the future kingdom of God the Almighty soon to be issued into the world.

Besides specific instructions on what prayers are to be said during Communion, the reader of The Didache is also commanded, "Let no one eat or drink of your Eucharist except those who have been baptized into the name of the Lord" (Lightfoot and Harmer, 154). Unlike some "relaxed" communion services held today in various religious communities, The Didache directs this ceremony with exact purposes, provisions, and prohibitions.

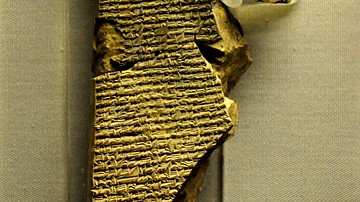

Even more specific than the Eucharist, The Didache presents special rules on baptism. Certain ingredients must be present for this act to be legitimate to the Christian church: water of specific type and condition, personal preparation in the form of fasting and instruction, and correct theological phrasing on the state of the baptized. This creates a baptismal formula that is even used in modern times but has its origins in the Jewish faith. However, as Niederwimmer suggests, "The Didache is not, of course concerned with Jewish rites of lustration but with the sacrament of baptism. . . . The Jewish tradition is still influential, but in principle it has already been ruptured" (153-154). The Didache sets up the distinctness of Christian baptism compared to Jewish practices and emphasizes the spirituality behind the act.

The Didache also touches on other miscellaneous liturgical practices such as tithing, fasting, fellowship and charity, and hospitality. In each of these, a generalized statement is made about what should be done, and then the writer of The Didache explains the reasons behind sponsoring such practices. For instance, it advises readers to give all the firstfruits to the prophets or the poor, "in accordance with the commandment" (Lightfoot and Harmer, 157), and "Do not let your fasts coincide with those of the hypocrites" (153), so fast instead on Wednesdays and Fridays. Additionally, believers ought to gather together for fellowship and perform acts of charity, "just as you find in the Gospel of our Lord" (157). Moreover, they were to welcome everyone, "in accordance with the rule of the Gospel" (145).

Whether speaking on the Eucharist, baptism, fasting or prayer, The Didache shows itself as a useful "manual of church order and practice" (Lightfoot and Harmer 145). It offers a specific agenda or course of action to take as a church member in the body of Christ.

Moral Instruction

The Didache also focuses on the aspects of Christian morality and personal integrity and provides teaching on the two ways that a church member can take - one leading to life; the other, to death. Basically, in the era of Pax Romana, it shows the true pathways and roadblocks of Christian ethics.

Borrowing much from scripture, this document points to Jesus and his teachings as to what constitutes a holy life. In its first chapter, The Didache promotes love for God and neighbor as a primary rule of living. The church members are called to deny themselves for God and humanity and to be sacrificially altruistic. Furthermore, church members are to live according to a number of moral rules - some right out of the Ten Commandments, but others (and this perhaps shows the Romanizing influence of the times) deal with sexual promiscuity of classical Greek or Roman culture. It is stated, "You shall not corrupt boys" (Lightfoot and Harmer, 150). As such, the Didache's commandments appear to be a more specific breakdown of the two Great Commandments.

Later in chapter 3, The Didache pushes for a pure life and to "flee from evil of every kind, and from everything resembling it" (Lightfoot and Harmer, 150). The Didache not only promotes specific church practices but also cultivates the personal practices of the church member. As such, holiness, morality and high ethical standards are important. Although the majority of The Didache deals mainly with the rules -personal and public - of the early Christian, in chapter 16, it presents to its readers the necessity and purpose of these prescribed attitudes and practices.

It is crucial to understand the mindset of the early Christian Church. There was an "eschatological sense of imminence" (Werner, 22) that Jesus would return to establish his kingdom. Therefore, it was quintessential that the early Christians maintain a holy life until the end lest they lose the gift of eternal life given to them by God through Jesus Christ. The writer of The Didache makes several eschatological references in the prayers offered earlier in chapters 8-10 such as "Your kingdom come" (Lightfoot and Harmer, 153) and "so may your church be gathered together" (154).

These statements are a congealing factor bringing The Didache's prolific instructions on church practices and personal morality together. The eschatological hope was that Christ's return was going to occur very quickly, so church leaders had to maintain a level of holiness in order to be found blameless. Although this hope had its origins in the New Testament, the Fathers like Rufinus still considered The Didache "not 'canonical' but 'ecclesiastical'" (Schaff, 558). Its usefulness as a church manual on practices and the catechumenate was important but, for theological purposes, its evaluations lacked the substantiation and spiritual depth of other books in the New Testament.

Conclusion

The Didache provided the early church with an instruction manual on how to deal with very complex issues, both in the personal and public arena. Its brevity should by no means lessen its importance for many other works written later on by other minor apostolic fathers seem to have been modeled after it (the Syriac Didascalia, the Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus of Rome, and the Constitutions of the Apostles).

What can be surmised (and with a fair amount of confidence) is that The Didache aided a great number of people in the early church (and perhaps even today) to focus, through liturgy and moral practice, on what it means to be a Christian. Faith was not just a feeling of spirituality; it required a great deal of effort and respect in its expression within the church and in the world.