The Romans constructed mills for use in agriculture, mining and construction. Around the 3rd century BCE, the first mills were used to grind grain. Later developments and breakthroughs in milling technology expanded their use to crushing ores in mining and such construction activities as cutting wood and marble. Mills became an important part of the Roman economy, decreasing the reliance on human labour, and dramatically increasing productivity and efficiency in many sectors of the Roman economy.

MILLS USED IN AGRICULTURE

Hand-driven Mills

In the agricultural sector, mills allowed for the production of large quantities of flour which was essential to bread production. Before mills were ever invented, humans ground cereals with the use of saddle querns which consisted of a rounded stone pressed manually against a flat stone bed. The first significant innovation in milling came in the late 5th century BCE in Greece, with the introduction of the first milling machine: the Olynthus Mill, also known as the hopper mill. The Olynthus Mill consisted of rectangular-shaped lower and upper stones. The top stone had a long handle and was moved in reciprocal fashion from side to side. The mill also had a hollow cavity (or hopper) with a narrow slot at its centre through which the miller fed the grain.

Rotary mills were an improvement over the Olynthus Mill in that cranks could be attached to a beast for grinding. The animal-driven rotary mill appeared around the 3rd century BCE in Italy, one of the best examples being the Pompeian mill which is often associated with the rise of commercial bakeries. Such Pompeian mills were driven by two donkeys harnessed to a wooden frame. The mill consisted of two parts: the lower stone (the meta) and the upper stone (the catillus), both made of strong volcanic rock. The upper concave and hour-glass shaped catillus was turned by donkeys. It had a hole through its centre and a hopper at its top through which the miller poured the grain. This stone rotated against the lower meta stone which was slightly convex and immobile. The animal-driven rotary mill saved humans from the drudgery of milling and significantly increased the flour output and quality as donkeys could drive the mill for hours at a time.

Water-driven Mills

The watermill was another significant invention which, according to most historians, came later in the last century BCE, or slightly earlier. In this version of the mill, water striking paddles drove the upper catillus stone with much greater power than had been available from animals. Watermills could therefore produce even greater amounts of flour.

Many engineering challenges had to be solved for their construction. For example, a constant supply of running water was needed, with the ability to turn it off during inspections and repairs. This was addressed with mill-channels, sometimes several kilometres long, with a system of reservoirs and sluice-gates that could limit or cut off the amount of water admitted to the paddle wheels. In some cases, aqueducts rather than canals ensured a constant water supply.

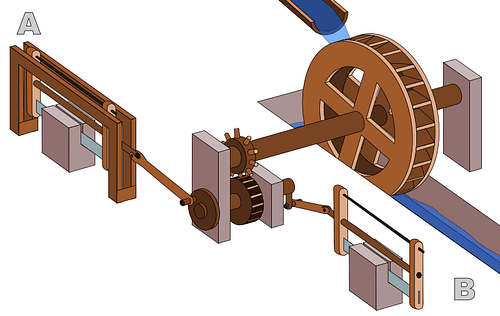

Another technical challenge was the conversion of the circular movement of the waterwheel to a rotation of the upper catillus or "runner stone" outside the water stream. In the horizontal-wheeled mill version, this movement was transferred directly to the runner stone by means of a vertical shaft. In the vertical-wheeled watermill, the vertical, circular movement of the waterwheel was converted to a horizontal rotation through the use of a right-angle gear. The right-angle gear, invented about 270 BCE, was a transmission system consisting of two cogwheels which increased the velocity of the runner stone, thereby, generating additional power.

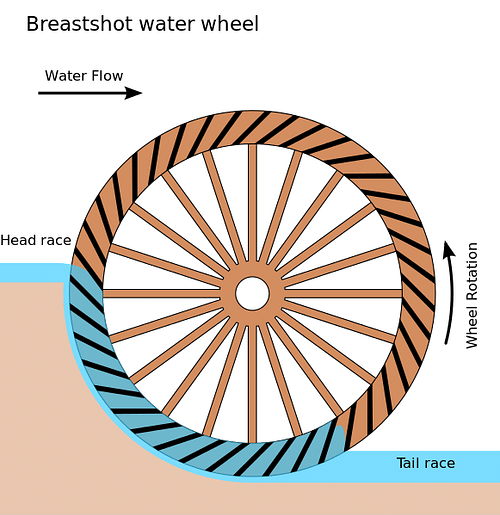

There were three variants of the vertical-wheeled mill:

- the undershot mill (water hitting the bottom of the wheel)

- the overshot (water hitting the paddles at the top of the wheel)

- the breastshot water wheel (water hitting the middle of the wheel)

The undershot mill was the simplest, earliest, and most common application of the three.

To justify a watermill's construction costs there had to be a large enough concentration of people (between 200 and 400 inhabitants in the surrounding area). When the population's concentration was even greater than this, clusters of mills were built, such as the Janiculum mills (early 3rd century CE) in Rome or the Barbegal complex (early 2nd century CE) in southern France. At the Barbegal complex, for example, an aqueduct could supply water to sixteen overshot wheels while on the slope of the Janiculum hill in Rome, a large number of mills also used aqueduct water to produce flour on an industrial scale from the 3rd through to the 6th century CE.

MILLS USED IN MINING

Stamp mills were used in mining to crush ore from deep deposits into small pieces before further processing. The metal ores needed to be crushed down to a pea or walnut size before it could be smelted. At times, the mills were also used in metal working after the completion of the smelting while the metal was red hot. The presence of stone anvils with marks from trip-hammers at Dolaucothi and other ancient Roman mining sites is proof that stamp mills were widely used in this way to pound extracted ore.

These stamp mills consisted of waterwheels, cams and trip-hammers (mola). They first appeared in Greece around the 3rd century BCE, and then spread across Italy throughout the first century CE. Before this invention, such crushing of ores was done manually, which required a lot of men and effort. As was the case with grain mills, these stamp mills saved greatly on manpower, while also greatly increasing the speed of ore processing. Stamp mills were mostly used in mining applications, but at times were also used to pound and hull grain.

Because water powered these stamping machines, aqueducts were often constructed near mining sites. For example, at the Dolaucothi mines in Wales, or in the Rio Tinto in Spain, long aqueducts were built to power a number of such stamp mills. There, aqueduct water was used as well in ore extraction techniques known as "hushing" and "ground sluicing". Some metal ores such as gold needed to be finely ground in order to release the tiny metal particles from surrounding rock, salts and sands. For this purpose, the Romans constructed watermills similar to the previously mentioned agricultural ones, but these had even harder grinding stones.

MILLS USED in CONSTRUCTION

The sawmill was another example of a surprisingly-sophisticated machine which consisted of a reciprocating saw powered by a waterwheel. It could cut large amounts of wood or stone, thereby saving enormous amounts of effort and labour. The waterwheel was connected to a rod linked to one or multiple crank-activated saws. The earliest known sawmill was the Hierapolis mill dating back to 250-300 CE. It was the earliest known machine to use a crank with a connecting rod mechanism. A relief on the sarcophagus of Marcus Aurelius Ammianos (dating back to 250-300 CE), in the ancient city of Hierapolis near modern-day Pamukkale in Turkey, gives a clear representation of how it functioned.

Sawmills were also commonly used to cut marble. A Roman poet called Ausonius writes in an epic poem about the river Moselle in Germany in the late 4th century CE and describes the shrieking sound of a water-powered sawmill used to cut marble. These sawmills were also used to cut various other types of stones. Sawmills dating from the 6th century CE were also found in Gerasa (in modern-day Jordan) and Ephesus (in modern-day Turkey). Therefore, it is safe to say that they were used throughout the Roman empire for various uses.

CONCLUSION

The invention of mechanically-driven milling technology, and later of watermills, decreased reliance on human labour and greatly improved productivity in many sectors of the Roman economy, thereby, improving the daily lives of Romans. Watermills such as the Janiculum mills in Rome allowed for the production of flour and bread on industrial scales. Stamp mills accelerated ore processing at mining sites throughout the empire, while sawmills allowed for marble and other stones to be cut precisely and at record speeds. Roman milling technology progressed from manual to animal-driven rotary mills in the 1st century BCE, and then to the more complex water-powered and crank activated sawmills of the 3rd century CE. Many of the principles used in the construction of these early machines are still applied to modern mill designs today. Such mills are additional examples of the ingenuity, impressive design, and manufacturing skills of the Romans.