The society of Carthage was dominated by an aristocratic trading class who held all of the important political and religious positions, but below this strata was a cosmopolitan mix of artisans, labourers, mercenaries, slaves, and foreigners from across the Mediterranean. The city's population at its peak was somewhere around 400,000, and the international blend of skills and cultures was a recipe for success which led Roman writers to describe Carthage as the richest city in the world. Unfortunately for posterity, when Carthage was destroyed by the Romans so too was its history in many respects and details of how Carthaginian society functioned, the relations between classes, and the role of women especially, remain frustratingly elusive. Nevertheless, descriptions by Roman authors and surviving inscriptions from Punic stelae help reconstruct at least a partial picture of the social makeup of one of the ancient Mediterranean's most important cultures.

Aristocracy

The aristocracy of Carthage was not, as in many other ancient societies, based on land ownership but wealth, pure and simple. Undoubtedly, there were large estate owners in Carthaginian lands beyond the city proper, but property was not the exclusive ticket to power that it was in other ancient cultures. This meant that enterprising individuals, able to exploit the market conditions of the city where goods were imported, exported, and manufactured or cultivated on site, or those who were able to fund their own private trading expeditions to such rich lands of opportunity as Sicily and Spain, could rise to the very top of society and politics. Indeed, this was a criticism of Aristotle when commentating on Carthage – that such a preoccupation with wealth would lead inevitably to a self-interested oligarchy dominating society.

The most important positions in the Carthaginian government such as the Senate and its committees were not salaried, and so, by necessity, only those with a private income could afford to hold public office. Nevertheless, access to the elite was open to anyone who could acquire the financial means. It must also be mentioned, though, that the Carthaginians had a healthy respect for genealogy and political leaders were often recorded with not only their own names but also those of several previous generations. This would suggest that a handful of families who could trace their lineage back to the founding of the city and the original colonisers from Tyre had a distinct advantage in running for public office.

Priests

The elite class dominated the religious posts of Carthage too. The head of the priests (rb khnm) was also a member of the Senate and the influential Council of 104. A committee of 10 senators was responsible for state religious matters. Priests would have enjoyed a high status as they performed rituals and sacrifices (both animal and human) in honour of the Punic gods. Living an austere life and with distinctive shaved heads, the majority of their positions were hereditary. Inscriptions inform us that a chief priest was responsible for a particular temple and assisted by a lower category of priests (khnm). There were female priests, but once again, the details of initiation and duties of the priestly class remain unknown. Priests may have controlled education, of which we know very little, and also the libraries we know existed at the time of Carthage's destruction in 146 BCE.

Citizens

Citizenship was reserved for males indigenous to Carthage and gave the right to participate in the popular assembly of the city. Here issues of the day were discussed and proposals from the Senate approved or sometimes even rejected. In practice just how many ordinary citizens could afford not to work and participate in politics is debatable, and there may even have been a minimum wealth qualification. Citizens were organised into memberships (mizrehim) or family clubs which were distinguishable from each other via their devotion to a specific god, the profession of their members, or perhaps even composed of those who had fought together in battle. Such memberships regularly bonded through shared banquets.

Unlike in Greek city-states, most citizens were not expected to perform military service either in peacetime or war. There was a small elite Carthaginian army known as the Sacred Band and composed of 2,000 hoplites, but most of the city's military requirements were met by mercenary armies. This was possible largely because for much of its history Carthage only ever fought battles in foreign territory and the city itself was never threatened until Agathocles landed an army in 310 BCE and the Roman invasions of the Second and Third Punic Wars. It is not clear if Carthage's citizens were obliged to pay tax, such was the enormous revenue extracted from conquered territories. The prolonged prosperity of the city during much of its history, based as it was on the labour of others, was probably the most significant reason why the citizens of Carthage acquiesced to rule by an elite aristocracy. The absence of a large citizen army which had raised the collective political consciousness of citizens in other states such as those in Greece was, perhaps, another reason for the Carthaginians' seeming lack of interest in political power.

Women

Despite the importance of such goddesses as Tanit/Astarte in the Carthaginian religion and the myth of the city's founding by Queen Dido (Elissa), women were not granted citizenship and so could not participate in the political life of the city. Indeed, they remain largely silent in the already impoverished historical record of Carthage. Some women's names crop up as inscriptions on religious dedications where they are referenced to by either their husband's or father's name. Some dedications were jointly inscribed with a father and daughter's names. These conventions further confirm that Carthage, as with most other ancient societies, was a male-dominated society in every respect.

Artisans

Not just trading middle-men, the Carthaginians produced their own manufactured goods and so the city had a large number of pottery, glass, and metal workshops (producing weapons, jewellery, and everyday items), dyers, carpenters, and construction workers. The larger workshops would have employed both citizens and slaves for their workforce. Tradesmen lived in specific areas with potters and metalworkers congregating outside the city walls to the south and along Lake Tunis, for example. Artisans also formed guilds and collectively provided the money to improve and maintain their area of the city.

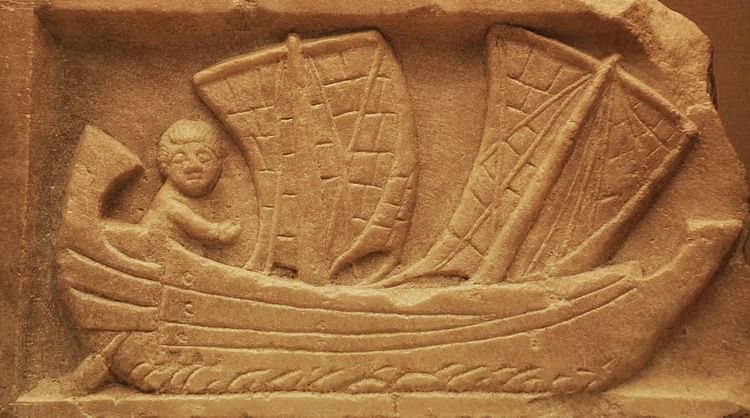

Less skilled workers but no less important to the city's industry were the dockworkers, porters, and sailors. Just like in any large city, there were all the professions needed for a thriving population with money to spend: teachers, doctors, architects, cooks, shopkeepers, cobblers, fishermen, scribes, chariot-makers, and so on. Then there were the artists who produced goldwork, sculptures, and fine glassware. Many of these professions are mentioned on Punic stelae. Working for their livelihoods this class would have included women, slaves, and foreigners, as well as male citizens. They lived in the large residential areas of the city in tightly-packed modest homes built of adobe brick, some even multi-storied (up to six floors) to house several families. The oldest such structures date to the 7th century BCE and so illustrate Carthage's prosperity and booming population early in the city's history.

Foreigners

Foreigners in the city came from the original founding city of Tyre in Phoenicia, from the conquered areas of North Africa (especially Libya and Numidia), Spain, Italy, and Sardinia. We also know that Carthage had a significant Greek community in the 4th century BCE. The presence of professional interpreters, as mentioned in stelae, is evidence of the cosmopolitan nature of Carthage. It is possible that citizens of allied city-states and those from Sidon and Tyre had certain privileges above those of other foreigners, and they would have enjoyed equality before the law, if not the political status, of Carthage's citizens proper.

Slaves

Slaves were either conquered peoples or brought from slave markets and were used for all manner of tasks, professional or menial, in the city and in the countryside, as well as in the Carthaginian navy during the Punic Wars. Just how many slaves were at Carthage can only be guessed at as richer citizens would have had many and poor citizens probably not even one. There is no evidence that a citizen of Carthage ever became a slave but, as in Rome, this may have happened if a person could not pay their debts or if poor parents sold their child, as was sometimes the case. There were cases of slaves becoming free, even if their new status is unlikely to have ever given them equal rights to ordinary citizens. Just how this might have been achieved is not known.

Inscriptions reveal that the relationship between slaves and owner was not always an entirely negative one. There are cases of slaves being allowed to run businesses for their master with relative autonomy and slaves returning to work for their former master after they had gained their freedom (although this may have been a legal obligation). One particular inscription, which notes a slave paying for his own dedication at a temple, implies that some slaves, at least, were able to accumulate their own money from their activities. Besides two slave revolts at the beginning and middle of the 4th century BCE, when slaves joined the rebel Libyans and then the Carthaginian leader Hanno in wider uprisings, there is no mention of any other unrest over the centuries. Their loyalty, rather, was expected and received in times of dire stress during the Second Punic War and the siege of Carthage in the Third Punic War when slaves were granted their freedom in return for military service.