Many myths and falsehoods concerning the Egyptian practice of mummification have been promoted to the general public in movies, television shows, and documentaries. While these offerings are entertaining and fascinating to watch, the purposes and details regarding the ancient preparation of the dead were quite complex, technically and culturally. Mummification was not merely done to protect the deceased body from decay and decomposition; rather, most ancient Egyptians practiced it—both the rich and the poor—to ensure a successful passage into the next life. Mummification was much more elaborate and far more of a regular, integral part of common Egyptian life than popular culture typically presents.

To gain a full understanding of mummification, the various cultural, religious, anatomical, and pragmatic aspects must be examined. Too often, the focus is solely on the gore and the fantastical lore. Moreover, the Hollywood image of a mummified body being placed in a great vaulted tomb, surrounded by beautifully painted walls, mounds of jewels and treasure stuffed in every corner, the body carefully wrapped with linen and tediously anointed with incense and bitumen, laid in an exquisitely carved sarcophagus of limestone, with vicious deathtraps all about to ensnare and execute the greedy grave–robber, is, generally, a gross exaggeration of the facts in the matter.

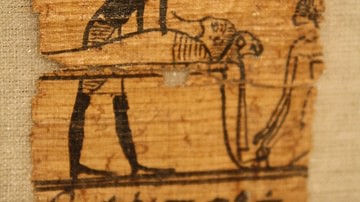

The Origins of Mummification

Certainly, there were funeral sites where the bodies were lavishly treated and surrounded with grandiose stores of wealth and affluence (the prestigious archaeological find of King Tutankhamun's tomb by Howard Carter in 1922 attests to this), but the reality is that humble, modest mummification ceremonies occurred more often than lavish ones.

As Wallis Budge states,

After the body had been steeped for a short time in bitumen or natron [a mineral salt], or perhaps merely rubbed with these substances, the few personal ornaments of the man were placed on it, he was wrapped in one piece of linen, and with his staff to support his steps, and his sandals to protect his weary feet in the netherworld, he was laid in a hole or cave, or even in the sand of the open desert, to set out on his last journey. (153-154)

In a culture such as Egypt's, which dates back thousands of years, a common question concerns the origins of this unique practice. What most learned egyptologists agree upon is that by the first dynasty, the Egyptians had enough medical and scientific knowledge to preserve the bodily remains of animals (even human) after death. In fact, the peasant magician Teta, during the reign of Khufu, the second king of the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt, wrote a book on anatomy and his scientific experimentation with drugs and herbs. Although it is most likely legendary, apparently, scientific inquiry ran in the family - even Teta's mother supposedly dabbled in biological and chemical experiments, eventually inventing an effective hair wash.

Although some historians dispute the notion that mummification dated this far back in the Egyptian timeline, citing many excavated tombs with unprepared, skeletal remains (although these might have been the result of human sacrifice of that period), most believe mummification had been going on for some time— such a complex process of anatomical preservation and culture hardly springs up overnight. The sophistication of the mummification process speaks of an operation that would have had to develop and evolve over a long period of time. Still, there is no specific historical or archaeological evidence to absolutely confirm when Egyptian mummification began.

Due to the religious associations with mummification, one would think that ancient religious documents would provide insight into the inception of mummification, but, once again, its religious origins are murky. Ward states, "The origins of Egyptian religion - we retain the term for lack of a better one - are lost in the pre–literate ages" (117). He further suggests that there is "no 'system' to clarify [Egyptian] funeral theology" (125) because much of its practices developed as the Egyptian polytheistic religion advanced and evolved through the centuries.

Theological background

With said Egyptian polytheism, much theological confusion and uncertainty arose, at times; in the ancient writings, Egyptian thought often appears to contradict itself. Although this might bother some from the Western influence, demanding consistency and empirical data concerning the possibility of the supernatural, a deity (or deities), and the human role in the afterlife, centuries of practice and acceptance show that Egyptians accepted such theological dissonance with ease. As Herodotus remarked, "They are religious to excess, far beyond any race of men . . ." (Book 2, Ch. 37)

Moreover, the whole idea of the afterlife was more of an effort of appeasement than a guaranteed event in Egyptian religion. Whereas the Judeo–Christian faith system includes (and depends on) a moral sense of balance and soteriology, the Egyptian's position was less tenable but not necessarily terminal. As Perry states,

A crucial feature of Egyptian religion was the afterlife. Through pyramid–tombs, mummification to preserve the dead, and funeral art, the Egyptians showed their yearning for eternity and their desire to overcome death. (12-13)

One of the strongest defining characteristics of the ancient Egyptians was the connection they felt between their lives and their environment. As Perry states, "The Egyptians also believed the great powers in nature—sky, sun, earth, the Nile—to be gods or the abodes of gods" (13). The terrain and climate that surrounded them could be savage and lethal; abundant life was tied into a relatively thin strip of land that depended on clever irrigation and yearly flooding (the gods willing). This preoccupation was further supported by the preserving nature of the Egyptian land, itself.

Due to a natural lack of moisture, decomposition in the desert was slow and thus, many living Egyptians would come upon the remains of their ancestors, long after their deaths, looking eerily similar as when they were first buried. This most certainly had a strong influence on their view of immortality, which is considered to be the "foundation of Egyptian religion" (Wallis Budge, 173).

The concept of immortality

Egyptian culture incorporated this concept of immortality quite nicely into their religious system through the Osiris myth. In fact, a minority of historians believe that Osiris was an actual real human being at one time in Egyptian history—perhaps an ancient ruler who experienced a civil war during his reign, and who received glory and deification post–mortem as the ancients often did for heroes of old. Regardless, the Osiris myth proposed that through the supernatural powers of Horus and the clever vengeful machinations of Osiris' wife, Isis, Osiris became a god and was reborn each year during the Nile's annual flood as Pharaoh of the land. His son, Horus, and his wife, Isis, would also be reincarnated in a continual cycle that guaranteed the royal divine lineage would never cease.

This story was not only empowering to the aristocracy in Egypt but also to all people in Egypt, according to Hamilton–Paterson and Andrews who write that with the great "power" of this myth, "The ordinary Egyptian could easily identify with him [Osiris]" (23). In a severe hierarchical society, it allowed the Egyptian peasant an opportunity to enjoy the good life beyond death, as with the Pharaoh; and joined them together in a divine, eternal religious practice. Evidence of this grand embrace of mummification can be found in such archaeological discoveries as the Valley of the Golden Mummies at the Bahariya Oasis, southwest of modern–day Cairo.

Budge gives a clear description of the purposes behind mummification. He states that mummification was used so that the Egyptian's

soul [Ba], and his intelligence [Ka], when they returned some thousands of years hence to seek out the body in the tomb, might enter into the body once more, and revivify it, and live with it forever in the Kingdom of Osiris. (Wallis Budge, 159)

To aid in this goal, carefully drawn out funeral rites were carried out to protect and secure the Ka for future life. The Ba was what the mummified body was called after it joined with the Ka. In the Ba, the Egyptian could "take on any shape he chose when leaving his tomb" (Hamilton–Paterson & Andrews, 18). Additionally, the Egyptian Akh was that portion of him which "dwelt among the stars rather than in an afterworld" (Hamilton–Paterson & Andrews, 20). He could, therefore, share immortality with Osiris, although he may not ever be equal to him.

Beliefs & Afterlife

As referred to earlier, in this process of death and reincarnation involving the Ba and the Ka, a contradiction occurs. Is the dead Egyptian's spirit in the tomb (or wherever the body was placed) or circling around the heavens? The question was unanswered in Egyptian theology. Nevertheless, Egyptians seem to have managed to set aside mutually conflicting ideas of immortality and allow for divine dissonance and limited understanding of the afterlife; however, events such as the dramatic shift to psuedo–monotheism of Akhenaten in the 14th century BCE suggest that Egyptian religious life was not set in stone, ironically.

One of the problems in understanding the religious concepts surrounding death and mummification is the impossibility of knowing how widespread and dogmatic these beliefs were in the whole of Egyptian society. Unfortunately, nearly all ancient Egyptian records are from the rich, royalty, or the priesthood. As Hamilton–Paterson and Andrews state, "So much is known about the upper–class ancient Egyptians' lives and culture that there is no longer any room for transcendental speculations" (20); however, the same is not true regarding the beliefs of the peasants in lower Egyptian society. The prevalence of magic and cults (as seen in the multitudinous references in tombs and burial sites) also include references to unheard–of, obscure deities and mystery religions, which suggests that not all Egyptians went along with the Osiris myth theological presumptions.

Still, one can still perceive a common thread in nearly all ancient funeral practices from the Old Kingdom to the New, despite any superfluous differences. Archaeologists and historians have been (and still are) astounded and impressed at the care and delicacy given to the deceased during the mummification process. No doubt, this meticulous and methodical treatment arose in ancient Egypt from a cultural sense of unity and hope in the afterlife, wherein decomposition just "upset so much theology" (Hamilton–Paterson & Andrews, 35).