For many people, the origins of the Christian church are shrouded in obscurity outside of the biblical narratives concerning Jesus Christ and his Jewish followers. Yet, after the crucifixion of Jesus and the initial missions work across the Mediterranean of Disciples and Apostles such as St. Peter, St. Paul, St. James, and St. John, other influential men and women spread the good news of Jesus Christ through ecclesiological cultivation and development.

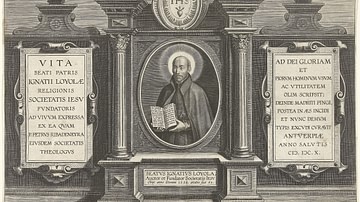

One such ancient church leader was Ignatius of Antioch (35–108 CE), a student of the Apostle John, the bishop of Antioch, the self–proclaimed "bearer of God" (Gonzalez, 51), and an eventual martyr for the faith. Though little is known about the charges for which he was condemned, on his way to Rome for his execution, "A number of Christians from that area came to see him. Ignatius was able to see them and converse with him. He even had a Christian amanuensis [a literary assistant] with him who wrote the letters he dictated." (Gonzalez, 52)

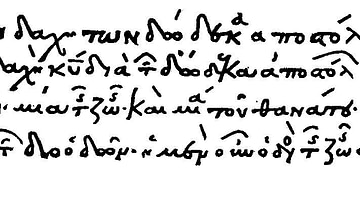

Letter to the Ephesians

Fortunately, for those hoping to learn more about early Christianity, Ignatius was able to pen at least seven letters during this time, which were later compiled with other Apostolic writings such as I & II Clement, The Letter of Polycarp to the Philippians, and The Didache. In fact, Lightfoot and Harmer commend Ignatius' letters "because of the unparalleled light they shed on the history of the church at this time and what they reveal about the remarkable personality of the author" (79). They show the environments and cultural attitudes within and without the ancient Christian communities and unveil how leaders of Christianity responded to both civil persecutions and heretical attacks upon the church and themselves, personally.

One of these works, Ignatius' Letter to the Ephesians, written sometime between 107–110 CE, imparts to the church at Ephesus (and future readers thereafter) Ignatius' exhortations, admonitions, and guidelines regarding parishioners' relationship with Christ, fellow church members, and non-believers. As Trebilco states, "Ignatius envisages the bishop having very broad and widespread control over the life of the community" (663). To this end, Ignatius specifically promotes and defends in the Letter to the Ephesians a strict-though-kind hierarchical structure within the church.

Church Hierarchy

Concerning the infrastructure of the church, Ignatius clearly favors a situation wherein the bishop holds the highest earthly rank of authority in the community, followed by the presbyters or deacons, and then lastly, the congregation members. Ignatius states, "It is obvious, then, that one must look upon the bishop as the Lord Himself" (Lightfoot, 88). He adds, "It is fitting, then, in every way to glorify Jesus Christ, who glorified you, so that you may be made perfect in a single obedience to the bishop and the presbytery and be sanctified in every aspect." (Lightfoot, 87)

Ignatius considered all churches and their flocks to be representative of Jesus' submissive relationship with God and Jesus' sacrificial attitude toward his followers. Thus, Ignatius encouraged the church at Ephesus to be "attuned to the bishop like strings to a lyre" (Lightfoot, 87), and to "obey the bishop and the presbytery with undisturbed mind" (Lightfoot, 93). Spiritual leaders in the church were established by divine appointment; thus, healthy congregations should live in humble subjection to the bishop, facilitating perfect harmony within the church.

No stranger to corrupt Roman and Jewish institutions, Ignatius was not ignorant of the dangers of a hierarchical system. Although the Christian persecutions were intermittent in the first three centuries CE, many followers of Jesus were martyred under the tyrannical reigns of emperors like Nero, Domitian, and Trajan, who used the persecutions to stabilize their empires (and to distract from their own leadership failings). As Galli remarks,

From A.D. 30 to A.D. 311, a period in which 54 emperors ruled the Empire, only about a dozen took the trouble to harass Christians. Furthermore, not until Decius (249–251) did any deliberately attempt an Empire-wide persecution. Until then, persecution came mainly at the instigation of local rulers, albeit with Rome's approval. Nonetheless, a few emperors did have direct and, for Christians, unpleasant dealings with this faith. (20)

Faithful submission

Having already observed and experienced this direct persecution, Ignatius maintained that the structure of power within the church body was not to exist for political sake; rather, church members should coexist in blameless union so that the church "may always participate in God" (Lightfoot, 87). For the early church, all humans (regardless of race or gender) were brothers and sisters under God, with Jesus Christ being their only Lord and King. Submission, then, was to produce a friendly family of faith—not a prison of the oppressed.

Ignatius suggested that if the flock faithfully followed the bishop and lived in peace with one another, the church "may sing with one voice through Jesus Christ to the Father, so that he may both hear you and recognize you, through what you do well, as members of his Son" (Lightfoot, 87). Ignatius went on to write, "When you frequently come together, the powers of Satan are destroyed and his destructive force is annihilated by the concord of your faith" (Lightfoot, 90). Thus, the hierarchical structure was not just to efficiently run the church; it had the more important function of promoting inner community bonds and to cultivate a larger force of spreading God's good news to the world.

Furthermore, as perfect love of God and one's neighbor was to be the hallmark of being a follower of Christ, Ignatius warned against anything that would impede God's truths, especially the false teachings and Gnostic assertions that had begun to infiltrate some Christian circles. He writes,

For there are some who with wicked guile are accustomed to bear the Name but behave in ways unworthy of God. You must avoid them as wild beasts, for they are mad dogs, biting in secret; you must be on guard against them, for they are practically incurable. (Lightfoot, 88)

Such false teachings and incorrect doctrine only led to a break in unity within the church and, even worse, a break of parishioners' relationship with God.

Legacy

Ignatius of Antioch's charge for the early Christian church was to be a productive and protective one. For this important Apostolic Father, the ultimate purpose of the church was to reach the world for Christ. Godly leaders (such as the bishop at Ephesus) created godly followers who followed the biblical tenets of true Christianity and avoided worldly false teaching that led only to destruction and division. With this in mind, Ignatius states, "Pray continually for the rest of mankind as well, that they may find God, for there is in them hope for repentance" (Lightfoot, 89).

Ultimately, for Ignatius, carrying out this divine commandment (cf. Matthew 25) began with and was anchored in submission and unity to God, church leaders, and all Christian followers.