Although many Christians, theologians, and denominations have advocated for the idea that all biblical texts within the canon are one in spirit, authority, and ultimate authorship, not every reader of the Bible has come to the same conclusion, historically. During the formation of the early Christian church, some heterodox readers suggested that there was a potential juxtaposition between the God of the New Testament and the God of the Old Testament. As Harland states,

At this time, more and more Christians came from a non-Jewish background, and Christian theologians began to measure themselves against the teachings of secular Hellenistic philosophy. Many branches of Christianity had to face this issue, the Gnostics no less than any other. (Harland, 306)

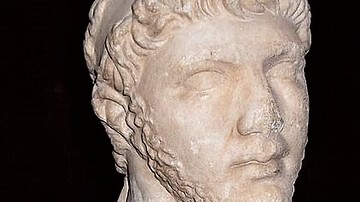

One such person was Ptolemy the Gnostic (also known as Ptolemaeus Gnosticus), who studied under the famous Gnostic teacher, Valentinius (c. 100 – c. 160 CE) and wrote a fascinating letter to his sister, Flora, discussing the integrity and authority of the scriptures.

Letter to Flora

Unlike the traditionalist view that holds that everything in the Bible is inspired of God (and therefore supremely equal in value), Ptolemy, like the Gnostics, considered some texts more godly than others; his interpretation followed "the principles of a Gnostic view of reality" (Froehlich, 12). Their approach to the scriptures was very hierarchical with some scriptures countering others in regards to their authorship or origin. As these Gnostics read the scriptures, it appeared to them that some commands and ordinances were frequently in conflict, indicating possible corruption of the biblical texts. Thus, they were perplexed about how to correctly interpret or assign words to/of God.

Ptolemy wrote a letter to his sister, Flora, in which he detailed how he thought the New and Old Testament texts should be evaluated. To him, the scriptures that came from God in the New Testament was profoundly more authoritative than the Old Testament (even though it, too, had God's touch upon it). He writes,

The Law of God, pure and not mixed with inferiority, is the Decalogue, those ten sayings engraved on two tables, forbidding things not to be done and enjoining things to be done. These contains pure but imperfect legislation and required the completion made by the Savior. (Froehlich, 40)

However, unlike the New Testament texts, which he claimed came straight from the good God, the Old Testament texts were often tainted by human influence (or the Demiurge or Demiourgos), which lessened their importance.

Challenging the radical literary critics, He writes, "For some say that it [the Mosaic Law] was laid down as law by God the Father. Others, however, leaning in the opposite direction, insist that it was ordained by the adversary, the destructive devil...Both sides are completely wrong" (Froehlich, 37). Ptolemy believed that the Old Testament law was a composite text created with authorship from God, Moses, and the elders of the people. God provided the Ten Commandments, Moses added to them to diminish the amount his people could sin, and the elders took over and changed it still, "legislating contrary to God" (Froehlich, 39).

Classification of God's laws

The true, good law was the one Jesus Christ purportedly received from God and handed to humanity in the New Testament. Supporting this position, Ptolemy states, "We shall draw the proofs of our statements from the words of our Savior, which alone can lead us without stumbling to the comprehension of that which is" (Froehlich, 38). Furthermore, showing his Gnostic influences, Ptolemy goes on to suggest that even God's laws can be divided into three hierarchical groups based on the opposition of spirit and flesh.

The first he deemed, "pure legislation" (Froehlich, 40) because it was not "entangled with evil" (Froehlich, 40) and was fulfilled through Jesus Christ. The second he considered "the legislation entangled with the inferior and with injustice" (Froehlich, 40) because it dealt primarily with inter-human relationships and which was "abolished because it was incongruous with his [Christ's] nature" (Froehlich, 40). The third group was made up of spiritually symbolic precepts that Jesus "transferred from the realm of sense perception and appearance to the realm of the spiritual and the invisible" (Froehlich, 40).

These were laws that had been metamorphosed into higher, grander ideals than they previously possessed. Thus, instead of circumcision of the flesh, after Jesus, one needed to experience the circumcision of the heart. As Ptolemy continues, the reader can sense a growing dichotomy between the Old Testament and the New Testament. Instead of one unified God made up of Father and Son, for the Gnostics, there existed a clear separation of deities and spiritual powers at work on the earth.

Demiurge

Controversial early church leaders like Ptolemy, Valentinius, and Marcion of Sinope (ca. 85 – ca. 160 CE), began to divide the scriptures as to what was authentically divine and what was corrupt. McGrath writes,

Marcion's core argument was that the 'God' of the Old Testament was not the same as that of the New Testament. The Old Testament God was seen as inferior, even defective, in the light of the Christian conception of God. There was no connection whatsoever between these deities. (21)

Marcion and the other Gnostics considered the Old Testament god to be the Demiourgos, or Demiurge, an "inferior deity to whom they ascribed the origins of the material universe, distinguishing him from the supreme God" (Livingstone, 164) and a supernatural concept that they borrowed/adapted from earlier Platonic thought. Somewhat ironically, Marcion's radical, disconnected vision of God, Jesus, Judaism, and the biblical story eventually earned him the title, 'The Greatest Heretic' by Justin Martyr (100–165 CE), who also promoted the idea of Seminal Logos, the seed of truth in all religions. Not surprisingly, Ptolemy's interpretation have also received harsh criticism by theologians through the centuries, because, as Fallon points out, "Ptolemy's conclusions take him to the very edge of metaphysics and myth" (Fallon, 306).

Regarding the Demiourgos, Ptolemy remarks,

He who stands in the middle between them [God and Jesus]...is neither good nor in any way evil or unjust...This god [the Demiourgos] will be inferior to the perfect God and lower than his justice. He is begotten, not unbegotten, for one only is the unbegotten Father from whom all things are because in its proper way everything depends on him. (Froehlich, 43)

Conclusion

Long before institutional Christian definitions of faith such as the Nicene Creed (325 CE) and the Athanasian Creed (5th century CE), Ptolemy's assertions in his letter to Flora raised further questions on the notions of homoiousis (Gr. of similar substance), homoousis (Gr. of same substance), and the relationship between the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit.

Reading through Ptolemy's Letter to Flora, one can perceive the great influence that his Gnostic beliefs held over his interpretations. Due to the Gnostic condemnation of all things temporal and of/from/by the flesh in the physical world, it is no wonder that he considered some scripture and Jewish laws delivered through human hands to be suspect and "bound up in evil" (Fallon, 46). Ptolemy's questions, ruminations, and interpretations, as suggested in his Letter to Flora, may be reasonable considering the scope, composition, and complexity of the Hebrew and Greek biblical texts; however, with a deeper, more holistic reading, the integrity of the holy scriptures may also be reasonably argued based on scriptural evidence of God (Yahweh) utilizing even banal methods to achieve his extraordinary purpose(s).