All too often, the Eastern perspective on the Trinity is mistakenly overlooked by Western society in the study of Church History. This is unfortunate, for men like Gregory of Nazianzus (329–390 CE) and John of Damascus (676–749 CE) offered insightful understandings in the first centuries of early Christianity regarding the theological understanding of the Trinitarian relationship in the Hebrew and Greek biblical texts. In their own literary works, both Gregory and John sought to answer questions concerning the equality of the members of the Divine Family, the distinguishing aspects of each person, the origins and procession of the Son and Holy Spirit, as well as the interaction and influence between them all.

Some fine examples of the doctrinal contributions of Gregory and John concern the equal standing of the Holy Spirit with the Father and the Son. As Sahinidou states,

The Eastern Church Fathers borrowed both the verb and the noun from Anaxagoras where it means revolution, rotation as cosmic differentiation, ordering, continuation, and extension. The noun περιχώρησις names the process of making room for another around oneself, or to extend one's self round about. (552-553)

Although these ancient theologians' interpretations may not be totally exhaustive, they are still valuable, nonetheless, in understanding the development of Trinitarian thought that began in the 4th and 5th centuries CE.

Gregory of Nazianus on the Spirit

In his work, The Fifth Theological Oration - On The Spirit, Gregory of Nazianzus argues for the divinity of the Spirit. In this oration, he provides his exhaustive depiction and discussion of the ontology and functionality of the Spirit and asserts its equality within the Divine Family. Opposing some 4th-century theologians who believed the Spirit to be subordinate to the Father and Son (and aligning with a key argument of the Cappadocian Fathers), he writes, "If he is in the same rank with myself, how can he make me God, or join me with Godhead?" (Nazianzus, The Fifth Theological Oration - On The Spirit, 196).

In Gregory's mind, the Holy Spirit must have equal status with the other godly members for "he is neither a creature, nor a thing made, nor a fellow servant, nor any of these lowly appellations" (Nazianzus, The Fifth Theological Oration - On The Spirit, 197). Appealing to evidence and logic, he suggests that any other understanding of the Spirit is unbiblical, "imperfect" (Nazianzus, The Fifth Theological Oration - On The Spirit, 198), and "absurd" (Nazianzus, The Fifth Theological Oration - On The Spirit, 197).

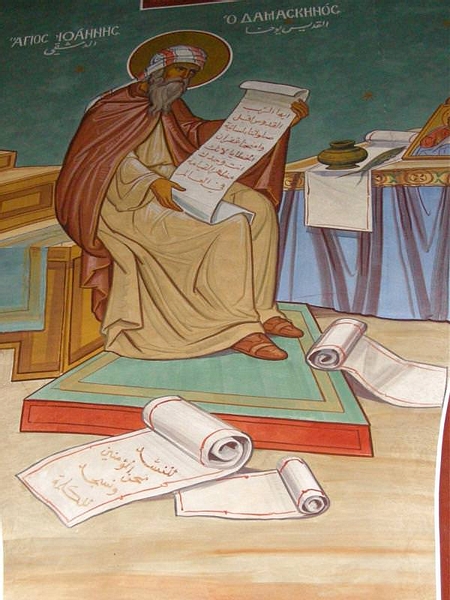

John of Damascus on the Trinity

John of Damascus also offers his take on this question of the Trinity. In Exposition of the Orthodox Faith, he remarks, "For the subsistences dwell in one another, in no wise confused but cleaving together" (Damascus, 10), and "the three holy subsistences differ from each other, being indivisibly divided not by essence but by the distinguishing mark of their proper and peculiar subsistence" (Damascus, 10). The Holy Spirit, then, is in equal unity and relation with the Father and Son. Although each member may focus on different roles, they are still of the same essence—meaning that throughout all is the divine nature and a divine interconnection.

Expanding upon their position on the Trinity, Gregory and John offer an even more detailed breakdown of the unique purpose and character of the Trinity, specifically of the Spirit. Gregory points out, "He is the Author of spiritual regeneration" (Nazianzus, Oration on Pentecost, 384). Furthermore, the Spirit is "Another Comforter, that you might acknowledge his co-equality" (Nazianzus, Oration on Pentecost, 383), and is the vehicle "by Whom the Father is known and the Son is glorified" (Nazianzus, Oration on Pentecost, 382). The Spirit has a distinctive mission suited to his divine character and talents. However, the Spirit also "shares with the Son in working both the creation and the Resurrection" (Nazianzus, Oration on Pentecost, 384). Therefore, biblically, the Spirit engages in certain unique activities (such as enlightening and sealing the salvation of believers, etc.), but is in ontological solidarity with the Father and Son and, at all times, in varying levels of participation with their activities, too.

John adds to Gregory's assertion when he succinctly states that the Holy Spirit exists "Having subsistence, existing in its own proper, and peculiar subsistence" (Damascus, 9). The Holy Spirit's subsistence is peculiar and unique. In other words, the Holy Spirit has the main focus of a particular activity even though the other members of the Trinity are still involved and supportive. This understood, John still maintains that the Spirit is "inseparable and indivisible from Father and Son, and possessing all the qualities that the Father and Son possess, save that of not being begotten or born" (Damascus, 9). Paradoxically, the Spirit is at one time distinguished from and yet unified with the other members of the Trinity.

Relationship of the Spirit and Son to the Father

Perceiving the conundrum this creates, John of Damascus attempts to further expound upon the relationship of the Spirit and Son to the Father. John suggests that the Father is the 'cause' of the Son and Spirit much in the same way that light is caused by a fire. He states, "Just as we do not say that fire is of one essence and light of another, so we cannot say that the Father is of one essence and the Son of another but both are of one and the same essence" (Damascus, 9). The two are intricately connected and one is not possible without the other. It is impossible to tell where one stops and the other begins, although some have differing opinions.

Countering the idea that the Spirit may proceed from the Son, John suggests that with its unique purpose and character, the Spirit "is one Spirit, going forth from the Father, not in the manner of Sonship but of procession" (Damascus, 11). Jesus may have been begotten, but the Spirit was not. He points out that to say that the very force that helped incarnate the Son could even proceed from the Son would be illogical (if not impossible).

As Gregory states, the Spirit is not just a "grandson God" (Nazianzus, The Fifth Theological Oration - On The Spirit, 197). Additionally, when the New Testament speaks of the "Spirit of the Son," John asserts that the term refers to the confession that the Spirit is manifested and imparted to humanity through the Son much like the way the Sun is manifested through its rays and radiance to the one seeing it. It is in the profound sense of revelation, not just association.

Human perception of the Godhead

All of these contributions to Trinitarian understanding are valuable for theologians; however, in many ways, Gregory and John's teachings (as well as others in the Eastern and Western perspective) are problematic. Their examinations are extremely useful in defining what the Holy Spirit and the rest of the Trinity members are not. Most of the questions of conflict that Gregory and John analyze and discuss revolve around the reduction of the divinity of the Trinity and/or the anthropomorphizing their characters. For these ancient theologians, this approach was definitely unorthodox thinking (and dangerous), as it went against traditional Judeo-Christian biblical precedent.

Yet, in attempting to define what the Trinity is, these Eastern theologians were still restricted to using human terms in their definitions. If the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are transcendent and supernatural, then any symbols attached to them can only be a partial reflection of what they really are, and any definition is limited by human communication and reasoning. John of Damascus attests to this when he states, "It is quite impossible for us men clothed about with this dense covering of flesh to understand or speak of the divine and lofty and immaterial energies of the Godhead" (Damascus, 13).

Furthermore, the human perception of the Godhead, then, is limited to what one experiences concerning God and what one reads in the Bible of his essence and attributes. As Tertullian, the Father of the Latin Church (c. 155 – c. 240 CE) put it,

For by whom has truth ever been discovered without God? By whom has God ever been found without Christ? By whom has Christ ever been explored without the Holy Spirit? By whom has the Holy Spirit ever been attained without the mysterious gift of faith? (Tertullian, A Treatise on the Soul).

Wesley, the founder of the Methodist movement also proclaimed, "Indeed, how can we expect that a man should be able to comprehend a worm. How much less can it be supposed, that a man can comprehend God!" (Wesley, Sermon 67).

Furthermore, human experience and perception is always influenced by the surrounding culture, which could shift the focus one way or another. Thus, the Eastern perspective is valuable, but it cannot fully encompass the whole of Trinitarian thought as its interpretation is limited by social influencers/restrictions and cognitive limitations of its examiners—as is true for all past and future theologians.

Conclusion

Despite these complications, both Gregory of Nazianzus and John of Damascus courageously and resolutely sought to answer very difficult questions and explore various controversial assumptions regarding the Trinity. The conclusions they came to may not be conclusive, but through their efforts to safeguard doctrinal truths, they battled what they considered to be heretical thought and, in turn, helped enlighten the world to a logical, more systematic, functional understanding of the relationship between the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Modern theology is truly in their debt for, in a great sense, Gregory and John took the question of the Trinity out of sheer speculation and moved it into the realm of scholarly contemplation, scrutiny, and study.