In 313 CE, Constantine the Great (272 – 337 CE) ended the sporadic-yet-terrifying Christian persecutions under the Roman Empire with his “Edict of Milan,” and brought the Christian church under imperial protection. Not surprisingly, public social activities and normative culture changed, quite dramatically and favorably, for the early Christians. Previously, early Christians faced dangers from outside of the faith and often had to “worship underground,” in order to avoid both physical dangers and social oppression from various Pagan and Jewish factions in the first three centuries of the faith. However, after Constantine's imperial endorsement and favoritism for Christian leaders and the laity, a new cultural permissiveness and secularism arose within the faith; and pious believers began to worry more about inner church immorality, abuse, and vice.

Beginning of the MOnastic Movement

Gonzalez writes, “The new privileges, prestige and power now granted to church leaders soon led to acts of arrogance and even to corruption” (143). As such, many in the primative Jesus movement sought a different, less secular, more purist environment in which to pursue their spirituality. MacCulloch states, “It was hardly surprising that the sudden sequence of great power and great disappointment for the imperial Church in the West inspired Western Christians to imitate the monastic life of the Eastern Church” (312). Thus began the official monastic movement in the West.

This Christian monastic lifestyle was simple at first, but, as is common to all societies, its routine became more and more convoluted and variegated with each passing century. One could find monks and nuns in caves, in the swamp, in a cemetery, even 12 metres (40 feet) up on stylite - all proclaiming God's calling and affirmation of their personal lifestyles. Eventually, specific rules and over-arching regulations were developed by the church institution to align all the numerous, specific groups into healthier, more consistant expressions of Christianity in the monastic movement.

The origin of the monastic movement begins in the 3rd and 4th centuries, CE, in the deserts surrounding Israel. As Nystrom notes,

Scholars have searched widely for the antecedents of Christian monasticism, hoping to find its pre-Christian roots in such possible points of origin as the Jewish Essene community at Qumran near the Dead Sea and among the recluses associated with the temples of the Egyptian god Sarapis. Thus far, no clear links have ben established to these or any other groups (74).

The Monastic Life

Although little direct evidence exists amid a plethora of colorful and inconsistent stories, these dedicated ascetics were known, historically by their special approaches to the Christian faith and by their local community approval. They were not part-time Christians. Their all-or-nothing attitudes, disenchantment with society, and desire to effectively influence the world (without being of the world) led them to renounce all creature comforts in order to utterly devote themselves to spiritual work such as praying, social services for the community, teaching, and spreading the Christian faith. Additionally, this was not a singular gender affair; many female monastic communities were also established throughout the centuries. Thus, many female believers were empowered in the monastic movement to exercise and utilize their personal gifts, becoming nuns, hermitesses, Beguines, Tertiaries, or anchoresses - a unique feature in that patriarchal age.

Early Monastic Leaders

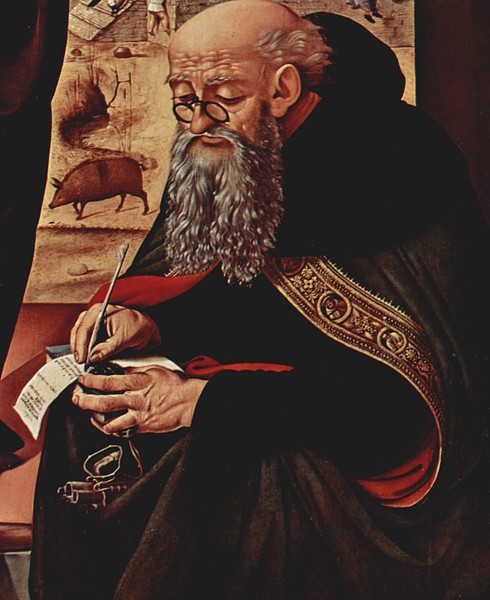

Several early monastic leaders or models are discussed and detailed in the early church fathers' (and mothers') writings. Saint Anthony of the Desert (c. 251 – 356 CE) was said to be an Egyptian holy man who initially lived as a hermit “. . . in the desert lands along the Nile” (Nystrom, 74), but later “He came out of his solitude to organize his disciples into a community of hermits living under a rule, though with much less common life than the later religious orders had” (Livingstone, 29).

Another Desert Mother, Amma Syncletica of Alexandria (c. 270 – c. 350 CE), dedicated her life to God after the death of her parents and,

. . . gave all that had been left her to the poor. With her younger sister Syncletica abandoned the life of the city and chose to reside in a crypt adopting the life of a hermit. Her holy life soon gained the attention of locals and gradually many women came to live as her disciples in Christ (The Desert Fathers, online).

An important and influential member of the monastic movement, her writings were also included with those of the Desert Fathers.

Others soon followed such as Saint Pachomius (ca. 290 – 346 CE) who helped establish cenobitic monasticism and established a monastery at Tabennisi, ironically on an Island of the Nile in Upper Egypt. One of the first to be called "Abba" (where the word "Abbot" comes from), he originally was pressed into the Roman army and was influenced by the Christians that he met in his work in Egypt. As Gonzales states, “Although not its founder, Pachomius deserves credit as the organizer who most contributed to the development of cenobitic monasticism” (165).

The Spread of MonAsticism

In the 4th century CE, the monastic movement spread to the European continent when John Cassian (c. 360 – c. 430 CE), a “Desert Father” and friend of Saint John Chrysostom the “Golden-Mouthed” (c. 347 – 407 CE), founded this Egyptian-style monastery in Gaul (modern-day France). Cassian is somewhat controversial because of his mentors and allegorical position on the Christian scriptures, and for his mystical embrace of the three ways: Purgatio, Illuminatio, and Unitio. Nonetheless, Livingstone remarks, “His Institutes sets out the ordinary rules for the monastic life and discusses the chief hindrances to a monk's perfection; it was taken as the basis of many W[estern] rules” (101).

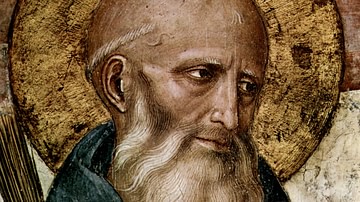

One of the most famous monastics (if not the most famous) was Saint Benedict of Nursia (c. 480 – c. 543 CE). MacColloch writes, “Benedict is a shadowy figure who quickly attracted a good deal of legend, lovingly collected into a life by Pope Gregory I [c. 540 – 604 CE] at the end of the sixth century” (317). He is credited with creating a monastic rule of order (although most scholars believe that Benedict borrowed some or much of it from “The Rule of the Master” or “Regula Magistri”) that was instituted and promoted as the standard for all of monasticism.

Yet, Benedict says of his new orders that it was “a little rule for beginners” and required “nothing harsh, nothing burdensome” of the monks. Compared to other rules (such as the Augustinian model), it was relatively flexible. His rule required monastic vows of stability (a lifelong commitment and permanence), fidelity (one's character can be shaped), obedience (one is submissive to superiors), poverty (one gives up all wealth entering into the community) and chastity (one forsakes all carnal knowledge and pleasure). Monasteries under this order placed high emphasis on the spiritual benefits of laboring, prayer, and a consistent schedule.

lATER Monasticism

In later medieval Christianity, Cluniac monasticism (c. 909 CE) accentuated simplicity of lifestyle, but even more so focused on prayer and mystic contemplation; and Cistercian monasticism (c. 1098 CE) developed when the emphasis shifted away from menial labor to religious duties. Eventually, Saint Francis of Assisi (c. 1181 – 1260 CE) established a mendicant (begging) order that promoted poverty as the vehicle to ensure a holy lifestyle. Although also a mendicant order, the Dominicans (c. 1220 CE) focused on poverty and scholasticism and sought to bring heretics back to the church through debate and apologetics.

With such an ever-growing, diverse, complicated expression of Benedict's “Simple Rule for beginners,” the monastic movement has often been criticized for promoting stoicism, alienation, arrogance, superstition, and judgmentalism throughout the centuries. Shelley responds,

Naturally, these conflicting views of the place of monasticism in the church have led to conflicting interpretations of the history of the movement. . . The key question is, how does renunciation relate to the gospel? Is it a form of self-salvation? Is it works righteousness, an atonement for sin based upon denial of the self? Or is it a legitimate form of repentance, an essential preparation for joy in the good news of God's salvation? (117).

Ultimately, the ancient Christian men and women who joined these monastic groups sincerely hoped to find escape, freedom, and victory over (and for) the world, and were willing to sacrifice all worldly goods and pleasures for conscience sake. As Chadwick states, “It was a theology dominated by the ideal of the martyr who hoped for nothing in this world but sought for union with the Lord in his passion” (177). Though the consequences may be “murky,” the causes, convictions, and sacrifices of those in the monastic movement is clear to see, at least historically.