Wine was the most popular manufactured drink in the ancient Mediterranean. With a rich mythology, everyday consumption, and important role in rituals wine would spread via the colonization process to regions all around the Mediterranean coastal areas and beyond. The Greeks institutionalised wine-drinking in their famous symposia drinking parties, and the Romans turned viticulture into a hugely successful business, so much so, that many of the ancient wine-producing territories still enjoy some of the highest reputations in the modern wine industry.

The Spread of WineMaking

The grape vine, which grows naturally in most geographical areas between 30° and 50° north with annual isotherms of 10-20 °C, was probably first cultivated (as vitis vinifera sativa) in the Caucasus region prior to the Neolithic period. From there the practice of pressing grapes into wine spread to the Near East and Mediterranean. Cultivated in Egypt, Mesopotamia, Phoenicia, and Mycenaean Greece, by the Classical period wine was an important feature of ritual and everyday life. As trade routes were established in the Mediterranean the consumption of wine and cultivation of vines spread from the Black Sea to the North African coast and along to the Iberian peninsula. Winemaking thus became one of the most visible manifestations of cultural colonization in the ancient world. Indeed, viticulture became so successful in Gaul and Spain that, from the 1st century CE, they replaced Italy as the Mediterranean's major producers of wine. In Late Antiquity, vine-growing spread further to include suitable northern European regions such as Moselle in Germany.

Wine in Mythology

According to Greek mythology, wine was invented by Dionysos (to the Romans Bacchus). The god generously gave Ikarios, a noble citizen of Ikaria in Attica, the vine tree. From this, Ikarios made wine, which he shared with a group of passing shepherds. However, unaware of the stupefying effects of wine, the shepherds thought they had been poisoned and so swiftly took revenge and killed the unfortunate Ikarios. Notwithstanding such an inauspicious start to the wine industry, this gift from the gods would become the most popular drink in antiquity.

Growing Vines

The Greeks, in particular, became passionate wine-drinkers, and so demand was always high. They knew that the three essentials of good soil, climate, and type of vine could combine to create differing varieties of grape and taste. While we know of many cultural practices and the mythology involving wine in the Greek world, it was the Romans who have left us the best descriptions of the process of making it.

Training vines to grow at the optimum height from the ground (which depends on local temperatures and wind), along a trellis if necessary, the optimum distance from each other, and regular pruning to strengthen the vine were all practices well-known to the Greeks. Vines could be left free-standing, supported with timber props, or even trained to grow up trees (especially the olive). This last method was prevalent in Roman vineyards with the best reputation for quality. Like most branches of agriculture, viticulture was a serious investment and profit margins could be slim indeed if wine was not produced on a large enough scale. As the Roman historian Varro put it, "there are those who claim that the cost of keeping up a vineyard swallows up the profit" (Bagnall, 7021).

Making Wine

The ancients knew full well the value of fine wines and distinguished their production between new young wines for the masses or armies in the field and more mature wines for the connoisseur. Certain places quickly gained prestige as good winemakers, notably the Greek islands of Chios, Kos, Lesbos, Rhodes, and Thasos.

In Italy, specific vineyards such as Caecuban and Falernian enjoyed a high reputation and were endorsed by such authors as Pliny the Elder, who wrote extensively on the subject. The Alban Hills near Rome, the region of Campania, and Northeast Italy were particularly noted for their quality wines. The industry became highly lucrative and regulations were imposed, as indicated in surviving inscriptions, concerning the sale of wine, its export, and guaranteed quality. Aside from large-scale producers, most estates would have had their own vineyards for private consumption. At Pompeii, for example, two-thirds of villas had vineyards.

Grapes were harvested and then pressed underfoot in large pottery vessels, baskets, stone vats, or on a simple tiled floor which sloped to a collecting channel. The process became more sophisticated with the invention of beam and weight presses which increased the crushing efficiency and which later evolved into even better screw presses from the 1st century CE.

Many vineyards from the Greek islands added sea water to the pressed must to make the wine smoother and increase acidity. Wines were both white and red, the latter gaining its colour from leaving the mash (marc and must) longer before fully pressing out the juice. A redder colour was also achieved by ageing the wine over a few years and even exposing the wine to heat by storing it in lofts built above hearths.

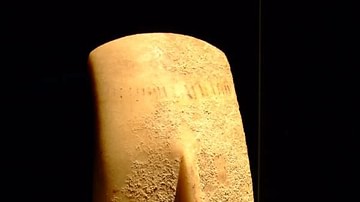

Wine was fermented in large storage terracotta jars, typically set partially into the ground in open-roofed buildings which had walls with apertures to allow a cool movement of air. When ready, wine was then drained off and stored in clay amphorae for transportation, usually sealed with a clay stopper or resin. Those amphorae destined for export were usually stamped to indicate their origin. Wine was sold in markets and, in the Roman world, dedicated wine shops. The Romans most valued sweet white wines (which would have been much cloudier than today's wines due to the more primitive production process). The Carthaginians had a similar taste, producing a famous sweet white wine made from sun-dried grapes. Wine was considered best as a pure drink without additives, but sometimes more unscrupulous producers and sellers did add substances (anything from spices to honey) in order to disguise the taste of poor wine or wine which had passed its best.

Drinking Wine

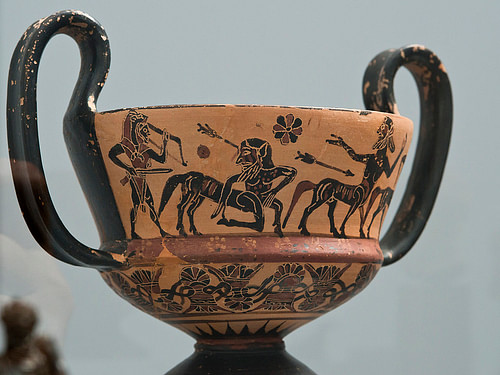

Wine was a common, relatively cheap, and everyday drink in both the Classical Greek and Roman cultures. It was drunk on its own and with meals. The Greeks diluted their wine with water (1 part wine to 3 parts water), although the Macedonians scandalously drank theirs neat. This dilution helped prevent excessive alcoholism, which was (at least by the elite) considered a trait of 'barbarian' foreign cultures and which was widely parodied in Greek comedy plays. Drunkenness also crops up in many Greek myths as an explanation for terrible and uncivilised behaviour such as the fight caused by the inebriated centaurs at the wedding of Perithous.

Ancient authors warned of the dangers of drunkenness to both mind and body. Aristotle even wrote a treatise On Drunkenness (now lost) and Pliny the Elder famously noted that wine can reveal the truth (in vino veritas) but that such truths are usually better left unsaid. Such learned recommendations, though, doubtless went unheeded by common folk and did not stop such famous names as Alcibiades, Alexander the Great, and Mark Antony gaining a reputation as fierce wine drinkers.

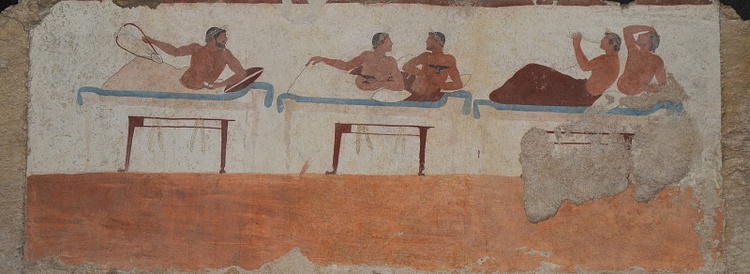

Wine was drunk on social occasions such as the Greek symposium, or drinking party, where elite male citizens would discuss politics and philosophy and be entertained by musicians and courtesans (hetairai). Special drinking vessels developed such as the shallow stemmed kylix which could easily be lifted from the floor by a drinker reclining on a couch. Large pottery vessels known as kraters were made so that wine could be easily mixed with water. The Roman equivalent to the symposium was the convivium where respectable women were added to the guest list and food had a greater emphasis.

Besides being a tasty drink and social lubricant wine had other functions such as in the pouring of libations to the gods in religious ceremonies. Wine, often healthier than unreliable sources of water, was also sometimes prescribed as a medicine by ancient doctors. This remedy was to be taken in moderation, though, as the ancients early identified the dangers of excessive drinking including insomnia, memory loss, a distended stomach, character changes, and early death. Wine was a gift from the gods but not to be over-indulged in or one would end up meeting them earlier than one hoped.

![Dionysos Mosaic [Detail]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/884.jpg?v=1726489864)