The celadon (or greenware) ceramics produced in ancient Korea during the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392 CE), are regarded as some of the finest and most elegant pottery pieces produced anywhere. With a pale green lustre reminiscent of jade and a super smooth glaze Goryeo celadons remain some of the most prized collector's items in the world of ceramics.

Etymology

The name celadon is a 17th-century CE French word of Greek origin used to refer to colours ranging from blue-green ('kingfisher') to soft grey-green seen in certain ceramics. The French had chosen the word as it was the name of the shepherd hero of the pastoral romance Astrée by Honoré d'Urfé. This character wore a striking green cloak and so the word came to be fashionable for describing particular greens. Celadon was incorporated into the English language from the 19th century CE for the same purpose. Ceramics experts, however, prefer to use the term 'greenware.'

Origin & Process

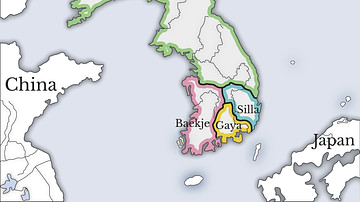

First produced in China, celadon wares quickly gained popularity across Asia and in Korea specifically from the 9th century CE when there was increased contact with the Song Dynasty. It may be that the colour association with precious jade was another reason for celadon's success. As one Xu Jing, an envoy from China, noted on visiting the Goryeo court, "Korean's call the green colour of ceramics jade" (Koehler, 24).

Initially, the Korean wares were rather crude, but by the 12th century CE Korean celadon ceramics, with their soft pale grey-green colour, were even finer than those produced in China. Again, Xu Jing noted that "The recent techniques are more sophisticated and the glaze even more beautiful" (ibid). Areas particularly noted for their skill at producing fine celadons included the Buan and Gangjin regions in the Jeolla Province of southwest Korea where the kilns were controlled by the government. The popularity and esteem with which celadons were held are attested by their presence in royal Korean tombs.

The green colour of celadons is achieved by firing the clay in an oxygen-reducing kiln with a glaze containing a low percentage of iron oxide (cheolhwa). It is the quantity of the latter which determines the hue of the green. Firing temperatures were around 1150 °C. The method gives an extremely smooth surface to the finished vessel although many fine cracks in the glaze are typical, even desirable.

With the Mongol invasions of the peninsula and the systematic destruction of workshops in the 13th century CE production of celadons was, unfortunately, brought to a halt. When potters were able to resume their work in the late 13th and 14th centuries CE, the wares were no longer as outstanding as previously, and the famous pale green lustre was replaced by an altogether darker and duller green finish. Today, modern workshops using traditional methods are once again producing celadon ceramics, especially in the 16 kilns of Gangjin, where there is an annual celadon festival.

Designs & Decoration

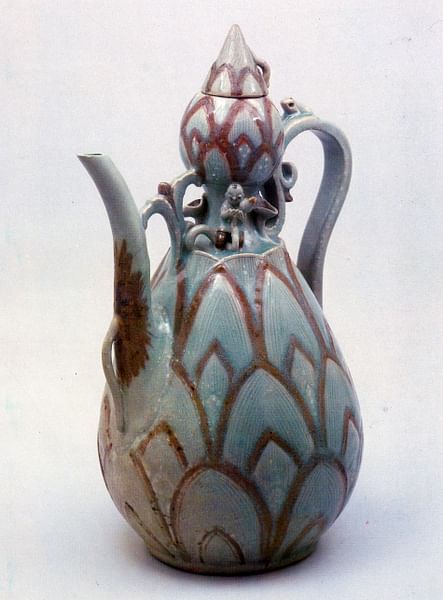

Korean vases are almost always tall and elegantly curved whilst other pieces such as those depicting animals and people are intricately carved. Vessels were decorated with low or high relief designs, especially floral patterns using the lotus leaf and flower, peony and chrysanthemum flowers, and birds such as waterfowl. Many motifs, especially cranes and clouds, are also associated with Buddhism (the state religion of the time), and more than one historian has noted, like Kyung Moon Hwang, that "these ceramics' almost indescribable sheen itself seems to evoke Buddhist spirituality" (42).

Vessels left undecorated often have simple linear designs engraved on them while others have more intricate black, red, brown, and white clay inlays in a technique unique to Korea known as 'Sanggam.' Here designs are carved on the surface and the inlays added before applying a translucent slip. Some later vessels were also inlaid with gold. The inlays are so fine and the workmanship of such a high standard that, on the finished vessel, they appear to be brush strokes. Adding a dark red colour to pick out designs or used for outlines became common in the later period of Korean celadons, achieved by using a copper underglaze - the first such instance in world ceramics. Another popular decorative effect was to add mouldings which could then also be made into openwork.

While vases, jugs, and bowls were the most popular shapes, potters also produced a myriad of other items using celadon. Ceramic pillows with carved lion figures supporting a smooth cross-section, pitchers in the form of Taoist monks or mythical dragon-fish creatures, incense burners (used in temples and private homes) with intricate cut-out designs and topped by animal figures through whose mouths the incense smoke exits, and even curvaceous roof tiles were all executed with the finesse seen in more classical vessels. Indeed, such was celadon's popularity that King Uijong had one of his royal pavilions at the Goryeo capital of Gaeseong entirely covered in celadon roof tiles in 1157 CE.

However, despite this variety in design, it is probably the maebyeong shape which best defines Korean celadon ceramics. These tall vases rise from a narrow base to an elegant and generously curved shoulder which ends in a small circular mouth. Many maebyeong vases, along with the finest examples of carved celadon wares, are on display at the National Museum of Korea and the Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, both in Seoul, South Korea.

This content was made possible with generous support from the British Korean Society.