This text is part of an article series on the Delian League.

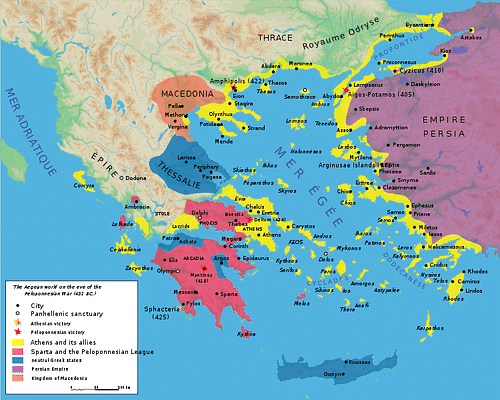

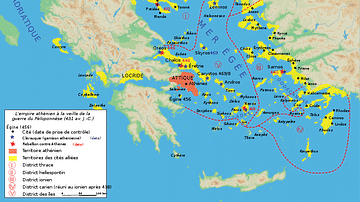

The second phase of the Delian League's operations begins with the Hellenic victory over Mede forces at Eurymedon and ends with the Thirty Years Peace between Athens and Sparta (roughly 465/4 – 445/4 BCE).The Greek triumph at Eurymedon resulted in a cessation of hostilities against the Persians, which lasted almost six years. Whether or not this peace or truce followed from some formal treaty negotiated by Cimon, son of Miltiades, remains unknown.

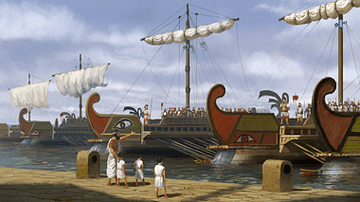

Nevertheless, the Greek success at Eurymedon proved so decisive, the damage inflicted on Persia so great, and the wealth confiscated so considerable that an increasing number of League members soon began to wonder if the alliance still remained necessary. The Persians, however, had not altogether withdrawn from the Aegean. They still had, for example, a sizeable presence in both Cyprus and Doriscus. They also set about to build a great number of new triremes.

REDUCTION OF THASOS & THE BATTLE OF DRABESCUS

A quarrel soon erupted between the Athenians and Thasians over several trading ports and a wealth-producing mine (465 BCE). Competing economic interests compelled the rich and powerful Thasos to revolt from the Delian League. The Thasians resisted for almost three years. When the polis finally capitulated, the Athenians forced Thasos to surrender its naval fleet and the mine, dismantle defensive walls, pay retributions, and converted the future League contributions to monetary payments: 30 talents annum. Some League members became disaffected with the Athenian reduction of Thasos. Several poleis observed the Athenians had now developed a penchant for using "compulsion." They started to see Athens acting with both "arrogance and violence." On expeditions, furthermore, the other members felt they "no longer served as equals" (Thuc. 1.99.2).

The Athenians, meanwhile, attempted to establish a colony on the Strymon river to secure timber from Macedon, which shared its borders with the west bank. The location also proved a critical strategic point from which to protect the Hellespont. The Thracians, however, repelled the League forces at Drabescus. The Athenians soon realized the threats from both Thrace and Macedon made permanent settlements in the region difficult as they were essentially continental powers, and the League fleet could not reach them easily. Designs for the region, however, would not change, and the Athenians would return there again.

The Delian League had by this time demonstrated an inherent conflict from its beginnings: on the one hand, it engaged in heroic struggles against the Mede and extended its influence, reaping enormous benefits (especially for its poorer members). On the other hand, it also suppressed its members and soon demanded obedience from them.

The League engaged from the outset in a form of soft imperialism, collecting and commanding voluntary naval contributions and tribute while Athens used those resources and led all expeditions, enforcing continued membership but also showing little or no interest to interfere with the internal mechanisms of any member polis (unless it openly rebelled).

CONVERSIONS TO TRIBUTE

More ominously, the larger poleis also began to grow weary fulfilling the prolonged obligations supplying the manpower and resources constant League operations required. A growing number of poleis elected instead to make simple monetary payments. Although Thucydides openly blames the allies for this change, commuting from contributions to tribute proves uncomplicated: cost (1 trireme = 200 rowers = ½ talent per month). A flotilla of 10 triremes required an outlay of 30 talents for a typical 6-month sailing season. Only the largest and wealthiest poleis paid anywhere near these sums.

Converting from resources to monies, however, had the two-pronged effect of both weakening individual League members while also greatly increasing the size of the Athenian fleet and thus Athens' overall might and influence. Athens, on the other hand, embraced these obligations and even commissioned 20 new triremes each year and would continue this undertaking until 449 BCE. By 447 BCE, in fact, only Chios, Samos, and Lesbos in addition to Athens still possessed substantial navies in the Aegean.

THE HELOT REVOLT & DISSOLUTION OF THE ANTI-PERSIAN HELLENIC LEAGUE

The Spartans, whose policies suffered not infrequent and often violent fluctuations with the constant power struggles between its Kings and Ephors, had, until the time of Thasos' revolt, appeared quite content to allow Athens unfettered leadership of the Aegean. Sparta nonetheless promised to help the besieged Thasians with an invasion of Attica, apparently motivated by growing trepidation over Athens' recent interference in internal Greek affairs. Before the Spartans could act on their pledge, however, a great earthquake struck the Peloponnesus (464 BCE), and the devastation resulted in the largest Helot revolt in living memory.

Helots (roughly akin to 'serf') originally descended from the Messenians, and Sparta remained the one Greek polis which held in total subjection large numbers of fellow Greeks.The Spartans thus possessed an inherently volatile and uniquely dangerous relationship with their enslaved Helots. Helots precariously outnumbered their Spartan masters, and they both equally feared and loathed each other. Sparta, now faced with an armed insurrection, appealed for assistance from the member poleis of the original anti-Persian Hellenic League. Aegina, Mantinea, and Plataea answered. 5.2.3).

Although the Athenian Ekklesia (Assembly) quarreled over an appropriate response, Cimon prevailed during the debate and persuaded the majority to remain on good terms with the Spartans. Athens dispatched a large force of 4,000 hoplites to aid Sparta against the rebelling Helots now holding Mt. Ithome. The boldness and revolutionary spirit of the Athenians shocked the Spartans. They unceremoniously refused Athens' assistance and dismissed the force. This unprecedented act of disrespect embarrassed Cimon and at first bewildered then angered the Athenians. The Athenian Ekklesia ostracized Cimon, renounced their membership in the original Hellenic League, and formed independent alliances with both Argos and Thessaly – two traditional Spartan antagonists. This strategic shift immediately brought Athens into conflict with Epidaurus and Corinth (460 BCE).

Shortly thereafter, Megara, because of Corinthian aggression, withdrew from the Peloponnesian League and allied with Athens. This further angered the Corinthians. In addition, Athens besieged Aegina. This Dorian polis, located in the Saronic Gulf, the "eyesore of the Peiraieus," had always threatened the waterway to Athens' main port (Arist. Rhet. 1411a15; Plut. Vit. Per. 8.5). Aegina resisted Athenian attempts to secure a foothold on the western shore but lost a large naval engagement against a Delian League fleet. When the Aeginetans surrendered, Athens forced them into the confederacy and to pay the very high amount of 30 talents annum (458 BCE).

THE EGYPTIAN EXPEDITION

Elsewhere in the Aegean, hostilities between the Hellenes and Medes resumed. Xerxes, the Persian King, had died in 465 BCE. After a year of internal political intrigue and infighting, Artaxerxes finally assumed the throne. The support he possessed from the various satraps, however, emerged unclear and in any case unsteady. The League chose to recapture the island of Cyprus with a force of 200 triremes, presumably to protect grain imports from the east (461/0 BCE).

When the Libyan prince Inarus appealed to the League in his own revolt against Persia, however, the synod, seeing this larger prize to the south, voted to divert the Cypriot Campaign to Egypt. The entire fleet sailed up the Nile to assist. Some of these ships would proceed to raid Phoenicia as well. The League's task force eventually began a siege of the Persian garrison at Memphis. Fragmentary evidence suggests further that the League also made attempts to extend its membership to Dorus, Phaselis, and perhaps other eastern Aegean poleis about the Caria District.

THE FIRST PELOPONNESIAN WAR

With the surrender of Aegina, Corinth, a Spartan ally, invaded the Megarid, now an Athenian ally, and the First Peloponnesian War became inevitable. The Athenians soon fought the Corinthians, Epidaurians, and allies of the Aeginetans as well as other Peloponnesians. The Spartans had seemed content to allow their allies to field the brunt of any conflicts they may have suffered against the Athenians. They held to this view even after Persia, prompted by the Delian League's actions in Egypt, attempted to entice the Peloponnesians to invade Attica with a large sum of money.

Spartan attitudes, however, changed when the Thebans also offered to war with Athens. Thebes recognized an opportunity had emerged with the sizeable Delian League fleet engaged in distant Egypt. The Thebans pledged that Sparta would no longer need to bring an army outside the Peloponnesus if the Spartans helped the Thebans re-establish their own Confederacy to check the growing power of Athens and the Delian League. The Spartans agreed. They had successfully quelled the Helot revolt, and the Peloponnesian League dispatched a force of 1,500 Spartans and 10,000 allies. Athens responded with a force of 14,000 Athenians and allies, including 1,000 Argives and a Thessalian cavalry, and the two Leagues clashed at Tanagra (457 BCE).

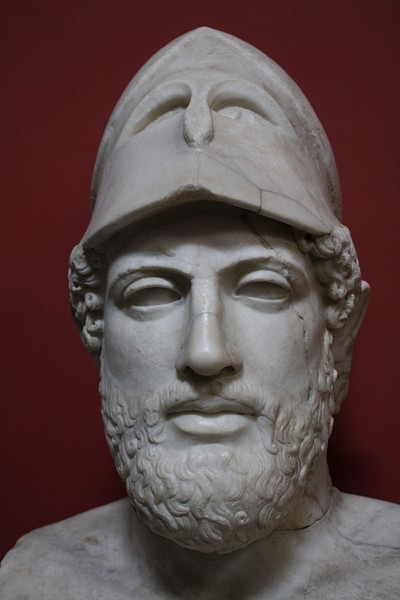

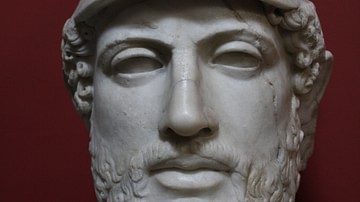

The Spartans, though victorious, no longer possessed the resources to continue operations in the region. They hastily negotiated a truce with the Athenians and withdrew from Attica. The Athenian-led force then defeated a Boeotian army at Oenophyta and overran Locris. The Delian League also dispatched a naval contingent to Sicyon and Oenidae under Pericles, son of Xanthippus. When Athens captured the Corinthian colony of Chalcis and forced both Orchomenus and Acraephnium into the League, the symmachy no longer existed as a purely maritime alliance; it had effectively established a continental presence in Boeotia.

AFTERMATH OF THE EGYPTIAN EXPEDITION

The Persians, meanwhile, counter-attacked in Egypt. They assembled a fleet of 300 triremes from the Cilicians, Phoenicians, and Cypriots, and drove the League forces from Memphis, trapping them on the island of Prosopitis. The resulting counter-siege would last 18 months. The Egyptian Expedition ended in total disaster (454 BCE); the bulk of the entire Delian League fleet, including 50 reinforcements caught at Mendesium, and approximately 40,000 men apparently lost. Only a handful of ships managed to escape. The catastrophe seriously weakened Athens' preeminent position in the League and threatened control of the Aegean. Soon thereafter, the poleis Erythrae and Miletus revolted (c. 452 BCE). The Athenians soon recovered them, however, restoring tribute, and installed Athenian officials and garrisons. They further required Erythae to provide sacrificial animals for the Panathenaic Games.

THE FIVE YEARS TRUCE & RELOCATION OF THE DELIAN TREASURY

The Athenians, after recalling Cimon from his ostracism, negotiated a more permanent Five Years Truce with Sparta (451 BCE) and turned their attention to securing the League. They quickly set about to rebuild the fleet, and the Athenians elected to continue installing local Athenian magistrates and plant garrisons after suppressing rebellions of member poleis, as they had done with Erythae. Sometime during these events (the precise date remains uncertain), the League, on a proposal made by the Samians, relocated its treasury from Delos to Athens. The disaster in Egypt most likely served as the impetus for this change, though this remains an educated guess.

By 454 BCE, the League treasury had accumulated a large surplus; sources attest anywhere between 5,000 and 10,000 talents. The Athenians elected to dedicate one-sixtieth of the tribute to Athena Polias, and then use any surplus to erect temples, support the Athenian fleet, provide work for its citizens, all while retaining anywhere from 3,000 to 5,000 talents on hand.

SIEGE OF CITIUM & BATTLE OF SALAMIS-IN-THE-CYPRUS

The Delian League recovered from its maritime losses with a decisive naval victory at Cyprus. The Athenians assembled a new fleet of 200 triremes under the command of Cimon to break Phoenician power in the southeast. The League laid siege to Kition after taking Marium. The League again diverted 60 of these triremes to Egypt, this time to assist Amyrtaeus in his rebellion against the Persian King. Cimon would die during the Cypriot Campaign.

The Delian League navy defeated a combined fleet of Cilicians, Phoenicians, and Cypriots off Salamis-in-the-Cyprus (presumably the same force that destroyed the League's fleet at Prosopitis), while also proving victorious in a pitched land battle. Even though Persia retained possession of the island, the League demonstrated a continued willingness and, more importantly, the capacity and ability to resist further Persian encroachments into the Aegean. The fleet then rejoined its Egyptian detachment and returned to Peiraieus. The Delian League would show little interest in Cyprus after these events.

THE PEACE OF CALLIAS

By the spring of 449 BCE, the Delian League apparently concluded some type of peace with the Persian King. This Peace of Callias still remains one of the most debated questions in Greek history, and the evidence does not admit certainty for or against its authenticity or provide the specific terms it dictated. Although Thucydides nowhere mentions it, 4th-century rhetoricians make clear that the Athenians had come to believe some formal peace ensued between Persia and the Hellenes following the Greek victories at Cyprus. Generally speaking, it appears the Athenians required the Persians to surrender control of the Aegean as well as the poleis on the western coast and in the Hellespont. In return, the League would abandon all aggressions against the Persian Empire.

After Eurymedon and Salamis-in-the-Cyprus, it had become nearly impossible for the League to undertake further profitable aggression against Persia. The Greeks could gain little by making deeper incursions into Asia Minor, and they also found it impossible to hold Cyprus given its distance from Greece and proximity to the Phoenician navy. Whether or not an official peace treaty ever existed, the Cyprus Campaign remains the final attested Hellenic operations against the Mede recorded. No Persian ship sailed west of Pamphylia, and no Greek trireme sailed east. Meetings of the Delian League synod, moreover, began to lapse, and this compelled Athens to make some decisions regarding its future.

The cessation of hostilities removed the immediate purpose for which the League designed tribute. Although the Greeks gathered at Byzantium intended for the League itself to exist in perpetuity, tribute existed originally to conduct a war against the Mede. The Tribute Lists for 454/3 show 208 poleis paying a combined total of 498 talents. By 450/449, the League dropped to 163 poleis paying 432 talents, and no quota list, in fact, exists for 449/8 BCE. The reasoning behind suspending tribute remains unknown.

THE CONGRESS & PAPYRUS DECREES

Sometime about that same spring (449 BCE), the exact date remains debated, the Athenians, on a proposal put forth by Pericles, son of Xanthippus, dispatched 20 heralds: five to Ionia and the Aegean islands, five to Thrace and the Hellespont, five to Boeotia and the Peloponnese, and five to Euboea and Thessaly. The Athenians invited all Greeks for a congress at Athens "to share in the plans for the peace and common interests for the Hellenes" (Plut. Vit. Per. 17).

Pericles sought to change the nature and focus of the Delian League from primarily conducting a war against Persia to promoting a Panhellenic alliance that would ensure a continued peace. In other words, war had brought the League together, let the maintenance of peace and security henceforth cement it. The Spartans declined to participate. Scholars debate the historicity as well as the intent (whether genuine or disingenuous) of this Congress Decree; not a hint of its existence exists outside Plutarch.

Shortly thereafter – though, again, the exact date remains debated – Pericles also proposed the Athenians secure the tribute reserve of 5,000 talents on the Acropolis and establish a commission to oversee the building of the Parthenon. The Athenians would further secure an additional 3,000 talents in reserve (in 200 talent contributions) while maintaining the fleet – but reduce the new annual commissions to ten new ships annum. The decree may also have established the 1,000 talent emergency iron reserve, which the Athenians could not use unless the Peiraieus came under direct attack.

Scholars refer to this as the Papyrus Decree, because the testimony survives on a mutilated papyrus from a commentary on a speech of Demosthenes. The decree stipulated that erecting temples with actual League funds had begun (after securing a surplus) but would not interfere with the maintenance of the Delian League fleet.The Athenians, therefore, showed no interest in relaxing League obligations. The tribute had become a necessity because the security of the Aegean depended on a navy; and navies, unlike armies, were enormously expensive. In addition, navies, again unlike armies, could not be brought into existence quickly to confront a threat. The only way the Delian League could possibly preserve any peace meant maintaining a visibly sufficient force solely for the purpose of preserving peace. Athens in fact annually dispatched a police force of triremes each year.

By this time, nearly all Hellenic poleis required imports of essential material and needed exports for their own surpluses. Athens, for example, needed timber and wheat, and this required unfettered shipping from the Euxine Sea and Macedon. The fleet also served as the League's foundation of power. Knowing that Athenian triremes might appear in harbor at any time became the first deterrent against anti-Athenian sentiment. Although some protest began to spread among those poleis some distance from the Persian sphere, Athens offered no compromises; the League would not dissolve, and yearly tributes resumed in 448/7 BCE and would continue.

INTERLUDE – THE ATHENIAN BUILDING PROGRAM

From roughly 450 BCE down to the late 420's BCE, the Athenians brought forth a series of new buildings and temples and enlarged key religious festivals. In many ways, these undertakings emerged simply as a continuance of Athens' desire, which had existed since at least the time of Peisistratos and his sons, to become the cultural center of the Hellenic world. Delian League resources now permitted them to continue this endeavor.

The Athenians sought to employ Ionian culture as a form of propaganda; opulent displays that appealed to broad Hellenic pride to counter some discontent the Delian League encountered amongst various allies. The Temple of Athene Nike (450-445 BCE), the Parthenon (447-432 BCE) and Pheidias' chryselephantine Athene (447-438 BCE), the Propylaea (437– 433 BCE), as well as the Erechtheion (421-405 BCE), coincided with the broadening of the Panathenaia and Dionysia festivals, and the Eleusinian Mysteries. These festivals would no longer serve as simply Panathenaic festivities but become Panhellenic celebrations. Allies would now participate in the sacred processions and sacrifices as well as in the dramatic and athletic contests.

Commissioners would report the finances of these celebrations in parallel with the assessment of Delian League tribute. Athens required further for allied poleis to bring a heifer and panoply to the Panathenaia as well as present a model phallus and their tribute during the Dionysia. The Athenians sought to display the three largest and most splendid Panhellenic religious festivals in the Greek world and sent forth heralds declaring that the allies would be directly and intimately involved.

The Athenians, in sum, attempted to present themselves as a majestic μητρόπολις or metropolis (lit. mother-polis) for all their allies. Athens would become the home or capital of a grand multiregional polis as opposed to leading a disparate collection of many independent and autonomous ισόπολεις or isopoleis (level or equal poleis). Without question, the high level of employment the building program created, coupled with the increased trade, brought with it a considerable population increase for Attica. Because Athens controlled the sea, "the good things of Sicily, Italy, Egypt, Lydia, the Peloponnese, and everywhere else [were] all brought to Athens" ([Xen.] Ath Pol. 2.7; Athen. 1.27e-28a).

THE SECOND SACRED WAR

During the same year the Peace of Callias concluded, Sparta launched the Second Sacred War. The Phocians had seized control of Delphi, ejecting the ἀμφικτυονία or amphictyony (League of Neighbors; lit. dwellers around) – a loose religious coopt that surrounded the Oracle of Apollo (sometimes referred to as the Amphictyonic League). Sparta restored the archaic Delphic authority and promptly withdrew. The Athenians promptly restored the Phocians.

Both Chaeronea and Orchomenus used this conflict to rebel from the Delian League, but Athens, after dismissing the objections of Pericles, dispatched a force of 1,000 Athenian hoplite volunteers and allied contingents under the command of Tolmides. He successfully captured Chaeronea but suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of a combined force of Boeotians, Locrians, Euboeans, and others at the Battle of Coronea (447 BCE).

Boeotia poleis revolted from the Delian League followed by Euboea and then Megara. Athens evacuated Boeotia, and a Spartan army again entered Attica. The Peloponnesians advanced as far as Eleusis. When Pericles led an additional hoplite force to meet the Spartans, they elected instead simply to return to the Peloponnese. The reasoning for this sudden reversal remains unclear, though later sources assert Pericles bribed the Spartan Pleistoanax. Pericles sailed for Euboea with 50 triremes and recovered the island after the siege and destruction of Hestiaia (446 BCE). The League, however, permanently lost Megara, who had grown disillusioned with Athens and put to death the Athenian garrison settled in their territory.

THE FINANCIAL DECREE OF CLEINIAS & COINAGE DECREE OF CLEARCHUS

The League Tribute Lists show 171 member poleis in 447 BCE, but only 156 in 446 BCE. Several poleis also made late or split payments during this time; others still made double payments. The Athenians needed to address irritating but nonetheless widespread and growing discontent throughout the Aegean that had resulted from both its conflicts with Sparta as well as some logistical problems that collecting tribute presented. The Financial Decree of Cleinias (447 BCE) sought to improve the discipline of tribute collection.

The Athenians attempted further to impose a common use of weights, measures, and coins throughout the League. It banned independent silver coinage, but only silver coin, not silver bullion. It also closed local mints. The effort met with limited success as larger poleis like Samos, Chios, Lesbos, and others about Thrace seemed to have continued minting freely (c. 449 - 446 BCE). This Coinage Decree of Clearchus makes no reference to the alliance and further presupposes the existence of Athenian magistrates in most allied poleis.

CLERUCHIES

About this time, Athens began to establish a κληρουχία or cleruchy (lit. apportionment of foreign land) after a polis revolted (e.g., Naxos, Andros, and Lemnos). The Athenian Pericles, for example, led an expedition to the Chersonese to protect it from Thracian invaders and settled it with Athenian citizens. A cleruchy, unlike an independent colony, was a group of Athenians settled on land seized from a rebelling polis, who retained their status as Athenian citizens. Cleruchies both reduced the growing idle and more impoverished population of Athens. They also established permanent local settlements of Athenians to insure against future rebellions from the League.

Cleruchies, however, also changed the nature and extent of the Athenian polis. The Athenians were no longer just the citizens residing in Athens but also those citizens who resided abroad. Since they remained subject to Athenian law, their presence extended Athenian jurisdiction. The Athenians, in other words, had come to interfere with the internal freedoms of other poleis, even fostering or supporting democracies when needed. Athens would go on to establish cleruchies in Imbros, Chalcis, and Eretia. Between 450 and 440 BCE, scholars estimate Athens sent forth at least 4,000 citizens. By 430 BCE, if we include the colonies established since 477 BCE, that number doubles.

The triumphs of the Delian League demonstrated larger inherent conflicts: on the one hand, it still required reasonable tribute, attempting now to advance a Panhellenic cause, while still ensuring the independence of Hellenes from the Mede. On the other hand, it more openly repressed dissenting members, forcefully acquired additional tributaries, while also extending Athenian festivals and law, founding democratic colonies, and imposing cleruchies on or near allied territory.

The Delian League had come to engage in a harder form of imperialism, expanding its reach while exacting tribute, and now requiring religious deference while interfering with the internal mechanisms of member poleis. The only poleis which still possessed significant fleets and remained independent were Lesbos, Chios, and Samos. Most notably, the language of decrees and treaties altered from 'the alliance' to 'the poleis which the Athenians control.'

This article is part of a series on the Delian League:

- The Delian League, Part 1: Origins Down to the Battle of Eurymedon (480/79-465/4 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 2: From Eurymedon to the Thirty Years Peace (465/4-445/4 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 3: From the Thirty Years Peace to the Start of the Ten Years War (445/4–431/0 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 4: The Ten Years War (431/0-421/0 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 5: The Peace of Nicias, Quadruple Alliance, and Sicilian Expedition (421/0-413/2 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 6: The Decelean War and the Fall of Athens (413/2-404/3 BCE)