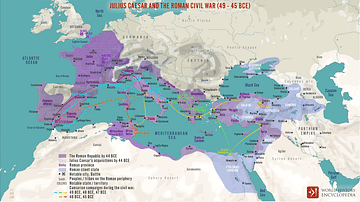

Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus were a pair of tribunes of the plebs from the 2nd century BCE, who sought to introduce land reform and other populist legislation in ancient Rome. They were both members of the Populares, a group of politicians who appealed to the average citizens and that opposed the conservative Optimates in the Roman Senate. They have been deemed the founding fathers of both socialism and populism.

Tiberius Gracchus

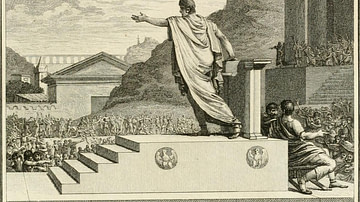

Tiberius Gracchus, born in 168 BCE, was the older of the Gracchi brothers. He is best known for his attempts to legislate agrarian reform and for his untimely death at the hands of the Senators. Under Tiberius' proposal, no one citizen would be able to possess more than 500 iugera of public land (ager publicus) that was acquired during wars. Any excess land would be confiscated to the state and redistributed to the poor and homeless in small plots of about 30 iugera per family.

The Senate was resistant to agrarian reform because its members owned most of the land and it was the basis of their wealth. Therefore, Tiberius was very unpopular with the senatorial elite. His main opponent was Marcus Octavius, another tribune who vetoed Tiberius' bills from entering the Assembly and whom Tiberius had previously gotten removed from office.

When King Attalus III of Pergamon died, he left his entire fortune to the people of Rome. Pergamon was one of the richest cities in the ancient world, and Tiberius wanted to use the wealth from Pergamum to fund his agrarian law. This was a direct attack on senatorial power and the Senate's opposition to Tiberius began to increase.

With his term coming to an end, Tiberius sought re-election as tribune for the following year. This was unprecedented, and his opponents claimed that it was illegal and Tiberius was trying to become a tyrant. On election, violence broke out in the Senate between Tiberius' followers and his opponents. Tiberius was beaten to death with wooden chairs and nearly 300 of his supporters suffered the same fate. These deaths marked a turning point in the history of the Roman Republic and a long-lasting association between violence and the office of the tribune.

Gaius Gracchus

Tiberius was succeeded by his younger brother, Gaius Gracchus, who was also a social reformer. He was quaestor in 126 BCE and tribune of the plebs in 123 BCE. He is generally considered to be a more complex and confrontational figure than Tiberius, and he had a much clearer legislative agenda that extended beyond simple agrarian reform. Some of his laws appear to have been directed toward the people responsible for his brother's death.

He renewed Tiberius' land law and founded new colonies in Italy and Carthage. He introduced a law that no conscription of Romans under age 17 would be allowed and that the state would pay for basic military equipment. Previously, a soldier of the Roman army had to pay for his own equipment, which was especially difficult for the lowest census class. Like his brother, he also funded state-subsidized grain. Another law passed by Gaius imposed the death penalty on any judge who accepted a bribe to convict another Roman guilty.

Gaius' opponents tried to win away his support, and he lost popular appeal by 121 BCE. After a riot broke out on the Capitoline Hill, and one of Gaius' opponents was killed, the ultimate decree of the Senate (Senatus consultum ultimum) was passed for the first time. This law gave the Senate the power to declare anyone an enemy of the state and execute him without trial by a jury. A mob was then raised to assassinate Gaius. Knowing that his own death was imminent, Gaius committed suicide on the Aventine Hill in 121 BCE. All of his reforms were undermined except for his grain laws. 3,000 of his supporters were subsequently arrested and put to death in the proscriptions that followed.

The tribunates of Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus began a turbulent period in Rome's domestic politics, and their careers and untimely deaths emphasize both the strengths and the weaknesses of the tribunate. In the following decades, the tendency toward violence became even more clear as numerous tribunes saw their time in office come to an end with their deaths.