This text is part of an article series on the Delian League.

The fourth phase of the Delian League encompasses the first part of the Great Peloponnesian War, also referred to as the Ten Years War, sometimes called quite incorrectly The Archidamian War, and it ends with the Peace of Nicias (431/30 – 421/20 BCE). Though the Ten Years War had several surprising events, the two alliances fought essentially within broad frameworks established by those who launched it. This Hellenic Civil War pitted a maritime power against a continental one; it resulted in a clash between democracies and oligarchies; it sought to dismantle competing alliances while consolidating their own; all while the Peloponnesian League presented an offensive strategy and the Delian League engaged in a defensive one.

"So roused were the majority against the Athenians, some wanting release from the rule, others fearing that they would be dragged into it" that most Greeks initially favored Sparta when King Archidamus finally led his army into Attica. Pericles, son of Xanthippus, in fact recognized the Athenians had indeed come to rule the Delian League "like a tyranny" (Thuc. 2.63.2).

The Spartans declared their goals nothing less than the "liberation of the Hellenes" and "to restore the independence of those poleis subject to Athens" (Thuc.1.139.3; 2.8.4). The Spartans finally agreed to launch the war, however, only because they feared Athens' overwhelming dominance in the Delian League and the spread of Ionian culture it represented, and they sought to destroy it.

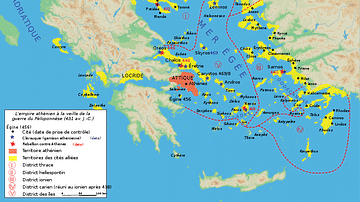

PELOPONNESIAN LEAGUE VERSUS DELIAN LEAGUE RESOURCES

The Peloponnesian League included all of the Peloponnese except Argos and a handful of poleis in Achaea. Outside the Peloponnese, it counted allies like the Megarians, Boeotians, northern Locrians, and Phocians. The Spartans also received assistance from Ambracia, Leucas, and Anactium, as well as Syracuse, and all the Dorian poleis of Sicily (except Camarina) and then Locri and Taras in Italy. The alliance could deploy about 100 Corinthian triremes.

The Delian League possessed all tribute-paying members on the coasts of Caria, Ionia, the Hellespont, and Thrace, as well as all the islands, "which lie between the Peloponnesus and Crete toward the east, except Melos and Thera" (Thuc. 2.9.4-5). Thera, however, would begin to pay tribute in 430/29 BCE. The Confederacy of Delos also had independent allies like Chios, Lesbos, and Corcyra, as well as Plataea, Naupactus, the Zakynthians, the bulk of the Acarnanians, Thessalians, and then Rhegium and Leontini in the west.

The Athenians possessed a ready fleet of 300 triremes, to which they could add if required a not insignificant number of aging vessels in varying need of repairs. The League could also acquire about 100 more ships from Chios, Lesbos, and Corcyra. Additionally, the Delian League possessed approximately 6,000 talents of coined silver on the Acropolis with 500 additional talents of uncoined gold and silver – and an 'emergency reserve' of 40 talents from the gold plates that covered the great statue of Athena. The League also realized an annual income of about 600 talents in taxes, duties, and fees, and approximately 400 talents in annual tribute.

The Peloponnesian League, on the other hand, possessed quite limited financial resources. The Corinthians argued they could rely on funds from the Delphic and Olympian treasuries and from specific allied contributions. Most Peloponnesian poleis, however, did not have significant resources, and the prospect the Spartans could use the two sacred treasuries seemed chimerical – in fact, they never did. The Spartans, however, promptly demanded ships from their allies in Sicily, though the magnitude of vessels requested (200-500 ships) would seem absurd. Regardless, they never received them.

King Archidamus further realized Athens stood like no other Hellenic polis: stout walls around both the city proper and its main port Piraeus defended the city – with the two areas connected by double long walls and a third connecting wall to its secondary port Phalerum. Even if the Peloponnesian League could deprive Athens of Attic land, the Athenians could still import supplies from abroad. Athens essentially had become an island to itself with the entire Delian League to defend it.

FIRST YEAR OF WAR: 431/30 BCE

Perdiccas of Macedon initially met widespread positive response from disaffected allies in the Chalcidice District following the revolt of Poteidaia. While the total number of poleis paying tribute in the area had dropped precipitously since the 440's BCE, the bureaucratic mechanisms Athens put in place to control the Delian League, especially Brea and Amphipolis, prevented any further seriously threatening large-scale rebellions to erupt. Sparta, moreover, found itself ill-equipped to aid these more distant disgruntled Athenian allies and limited its actions to invasions of Attica. The Athenians, on the other hand, elected to follow a strategy proposed by Pericles, son of Xanthippus: essentially fight a war of attrition.

The Peloponnesian army moved into Attica slowly and besieged Oenoe. The delay gave the Athenians time to evacuate their cattle and property to Euboea and retreat behind their great walls. 80 days after the Theban attack on Plataea, King Archidamus' army finally broke the siege and ravaged the Attic countryside. The Athenians did not engage, and the Peloponnesians withdrew when provisions became scarce. Athens would hold to this strategy each year, Pericles professed, until the Lacedaemonians recognized destroying the Attic countryside failed to yield desired results. At the same time, the Delian League navy would harass the Peloponnesians with seaborne raids.

The Athenians successfully razed the Peloponnesian coastline with a fleet of over 150 triremes: 50 from Corcyra and a handful from other League members. The Athenians also added Sollium, Astacus, and Cephallenia to the Delian League after advancing to Arcarnania (431 BCE). The Athenians, however, failed to take Methone, halted by the quick thinking of the Spartan Brasidas. The Corinthians, furthermore, would retake Astacus the following winter. Still, Delian League forces captured Thronium and took Aegina, where Athens placed settlers "to occupy and cultivate" the land (Thuc. 2.27). Ejecting the native population resulted in a loss of about 30 talents tribute, but it secured Piraeus. Athens further negotiated an alliance with King Sitalces of Thrace, who convinced Perdiccas of Macedon to side once again with the Athenians. Shortly thereafter, the Athenians fielded their largest army ever assembled: 13,000 hoplites and a large number of light troops. They invaded the Megarid. Though they did not conquer it, they vowed to invade twice each upcoming year.

Despite the apparent widespread dissatisfactions initially expressed against Athens during the Peloponnesian Congress, no seriously concerted rush to break away from Athens took place after Poteidaia, and when the Athenians called upon allied poleis to send contingents, they sent them.

For the first time in the Delian League's history, Athens dispatched squadrons of "money-collecting ships" (430 BCE). The Athenians resorted to this measure because they now fathomed facing a long and expensive war. Athenian control of the Delian League became threatened only in the east: Ionia-Caria and Lycia. Peloponnesian pirates interfered "with the merchantmen from Phaselis, Phoenicia, and those parts." Those six triremes sent to collect tribute also attempted to recover Caria and Lycia but failed (Thuc. 2.69).

SECOND YEAR OF WAR: 430/29 BCE

Neither the Peloponnesian nor the Delian League scored a decisive victory or suffered a catastrophic defeat during the first year of open war. Both sides seemed content to maintain this status quo. The Delian League assessment of 430 BCE, in fact, shows no radical departure or even a sign of anxiety from the years before the conflict began. Athens, furthermore, successfully added a handful of poleis to the League while containing (but not breaking) the rebellions that occurred. Such containment, however, would quickly grow rather expensive.

THE GREAT ATHENIAN PLAGUE

Athenian dispositions would begin to change after the second Peloponnesian invasion of Attica and the advent of the Great Plague (430-429, 427 BCE), which eventually claimed one-third of the Athenian population and, with it, their morale. Athenian demands on the League would begin to increase, and their reactions to revolts would become harsher as the war dragged on. In spite of the deaths occurring in Attica, Athens deployed 4,000 additional hoplites to crush the revolt of Poteidaia. They withdrew them when the plague swept the encamped army, killing 1,050 men.

The prolonged siege of Poteidaia would eventually cost 2,400 talents. When the polis finally surrendered the following year, the Athenian military commanders somewhat surprisingly permitted the Poteidaians to depart with a minimum of clothing and money (they then scattered to neighboring poleis), though this angered the Athenian Ekkelsia. The Athenians sent forth settlers. This moderation for Delian League members Athens displayed, however, would not last.

The Peloponnesian League attacked Zakynthos with ten triremes and 1,000 hoplites (430 BCE). They failed to take the polis but wrecked the countryside and withdrew. They then sent an embassy of Spartans, Corinthians, a Tegean, and an Argive to Persia seeking money and an alliance, but Athenians in Thrace intercepted and executed them.

THIRD YEAR OF WAR: 429/8 BCE

The Spartans and Thebans began a siege of Plataea. The Athenians, after suffering a defeat at the Thracian poleis of Spartolos and Poteidaia, changed tactics and elected to concentrate primarily on protecting those poleis that remained loyal (429 BCE).

The Delian League defeated a Peloponnesian naval force near Patrae and successfully defended the port of Naupactus. The Peloponnesians, however, soon advanced a fleet as far as Salamis before withdrawing, which shocked the Athenians. A brief war between Thrace and Macedon also alarmed many of the Delian League's members in that region.

Over the course of two years of war, the Delian League had apparently spent in the neighborhood of 4,000 talents. By the winter of the third year (428 BCE), they had only 945 talents in the reserve.

FOURTH YEAR OF WAR: 428/7 BCE

Any optimism the Athenians had at the start of the war had evaporated by this time. Plague losses proved nothing short of catastrophic (including the death of Pericles, son of Xanthippus), and, although the situation began slowly to grow more stable, word arrived that Mytilene had made preparations to revolt from the Delian League. Despite the failure of the revolts about Poteidaia, Mytilene consolidated the smaller poleis of the island, sent envoys to Sparta, and made preparations for the inevitable siege.

League forces, however, crushed the rebellion led by Mytilene on Lesbos – as well as the revolts of Antissa, Pyrrha, and Eresos – while easily repelling Spartan attempts to intervene and acquire their fleet. A Spartan force of 40 triremes under the command of Alcidas arrived too late and then made the situation worse by attacking and executing Athenian allies in the open sea. The Samians sharply chastised Alcidas that his actions proved a poor way "to liberate the Hellenes" (Thuc. 3.2-6, 8-18, 3.32, 35; Arist. Pol. 1304a9).

On the urgings of Cleon, son of Cleaenetus, who emerged as a prominent voice in the Ekklesia after the death of Pericles, the Athenians initially ordered the execution of all adult Mytilenian males and the enslavement of all women and children. They later reconsidered and decided to execute only those most responsible for the revolt (approx. 1,000 men). Athens then established cleruchies on the island.

Financial burdens coupled with the revolt of Mytilene compelled the Athenians both to impose a capital levy on themselves as well as demand an extraordinary assessment from the Delian League (428 BCE). The tax yielded 200 talents. They dispatched 12 triremes to collect tribute. In addition, Athenians made another attempt to retake the Caria District but failed once again.

The Spartans took Plataea, and a full-scale civil war erupted in Corcyra (428 BCE). Once again, this distant polis came to involve both Leagues. Although the Peloponnesians proved victorious in the opening naval battle, they withdrew upon the arrival of 60 Delian League triremes.

THE FIRST EXPEDITION TO SICILY

The Athenians dispatched 20 triremes to Sicily (427 BCE). Athens had a long-standing symmachy with Leontini, an Ionian polis, and it now faced war with Dorian Syracuse. Athens sought to deny Sicilian supplies to the Peloponnese and ultimately bring Sicily into the Delian League. The efforts met with mixed results: they won then lost Messana followed by several indecisive engagements. The Athenians would send 40 additional ships to assist, but, after the Congress at Gela succeeded in securing peace, they accomplish little more.

The Delian League now had 250 triremes deployed throughout the Aegean and in the west engaged in various operations. Cleon, son of Cleaenetus, and his companions represented a clear shift in Athenian disposition toward the allies of the Delian League. The chief aims became firmly maintained control, ensured tribute and contributions, and the belief that peace could ensue only after Sparta suffered humiliation and defeat.

TIGHTENING OF TRIBUTE COLLECTION

The Athenians finally stopped bleeding the Delian League treasury, caused by prolonged sieges, spending 100 talents of the reserve in 428/7 BCE and 261 talents in 427/6 BCE. Moreover, the Athenians had raised the assessment "little by little" over time (Plut. Vit. Ar. 24.3). By 426 BCE, the Delian League had 835 talents on hand.

Sieges had represented the greatest drain on the treasury, which occurred above and beyond normal wartime expenditures like ship and arsenal maintenance, crew training and exercises, and the building of new and replacement triremes.

![Athenian Tribute List [Fragment]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/5691.jpg?v=1599427803)

In 426 BCE, the Athenians reorganized tribute collection for the Delian League. They appointed individual Tribute Collectors in each polis, who the Athenian Ekklesia would hold personally responsible, and then five men would take charge to exact payments from all defaulters.

FIFTH YEAR OF WAR: 426/5 BCE

In addition to the annual invasion of Attica, Sparta founded a colony at Heraclea near Euboea. Meanwhile, Athens tried to force the Spartan colony of Melos into the League (apparently prompted by a recent monetary contribution to Sparta) with a sizeable force of 60 ships and 2,000 hoplites. When the Melians neither surrendered nor offered battle, the Athenians, not wishing to risk another long and expensive siege, departed. They nevertheless attacked Tanagra and assaulted Locrian territory before returning to Athens.

The Athenians again dispatched a fleet of 30 triremes around the Peloponnese to harass the area, joined by 15 Corcyran ships as well as forces from the Acarnanians, Zakynthians, and Cephallenians (426 BCE). The fleet took Leucus but was driven out of Aetolia, although it successfully halted Spartan and Corinthian encroachments near Ambracia.

PURIFICATION OF DELOS

The Athenian Ekklesia, celebrating the cessation of the great plague, voted to "purify Delos" (Thuc. 3.104.1; Diod. 12.58). Athens reorganized and made "more splendid" the island's quadrennial festival with musical, gymnastic, and equestrian contests (Plut. Vit. Nic. 3.5-7). These celebrations had steadily declined since their heydays of the 6th century. The Athenians sought to re-establish their prominence.

The festival once attracted Ionian Greeks from both the Greek mainland as well as the islands. The Athenians attempted to increase their "popularity" (Thuc. 3.104.3). They wished to build on their other endeavors to create Panhellenic celebrations since the Peloponnesians controlled three of their own. The Athenians appealed specifically to Ionian solidarity.

SIXTH YEAR OF WAR: 425/4 BCE

The next year, the Peloponnesian army again entered Attica, and Corcyra once again came under threat, besieged by 500 exiles and a Peloponnesian fleet of 60 triremes. The Athenians responded with a force of 40 ships, but they stopped to fortify Pylos, leaving a garrison and five triremes behind. The remainder then continued to Corcyra. The Spartans, though slow to react at first, soon understood the danger this fort represented. They withdrew the army from Attica and converged to destroy it. The Athenians held them off for two days.

PYLOS & SPHACTERIA

The Delian League's Corcyran force plus ten Chian and Naupactan ships returned and defeated the Peloponnesian fleet in the bay. The Athenians besieged 420 men at Sphacteria (where they had fled), which included 180 Spartans: one-tenth of the Spartan army. This sudden turn of events greatly alarmed the Spartans, and they immediately sued for peace. The Athenians responded with conditions unacceptable to the Peloponnesian League. When Athens sent reinforcements under Cleon, the surviving 292 Peloponnesians and 120 Spartans on Sphacteria shocked the entire Hellenic world by surrendering.

The events at Pylos changed the entire outlook of the Ten Year's War: with 120 Spartan prisoners, the annual invasions would end, and the Delian League fleet could sail throughout the Aegean unmolested.

EXPANSION OF THE DELIAN LEAGUE

The Athenians elected to make an extraordinary assessment in 425 BCE. The Delian League had but 674 talents in the reserve. The Athenians more than trebled the amount of tribute collected from the 450's to nearly 1,500 talents. They also added the new District of Euxine (the Black Sea). They dispatched the largest fleet recorded to collect tribute and declared further their intention to make more consistent assessments during the years of the Great Panathenaia (i.e., 420, 416, 412 BCE, etc.).

The Decree of Cleonymus, moreover, required the Hellenotamiai to report to the Ekklesia a full accounting within ten days of the Dionysia of tribute paid or not paid, as well as all partial payments. Additionally, the Decree of Thudippus appointed ten assessors to fix a provisional amount for each member, and, in no case, could they lower a figure (unless a polis proved unable to pay). Heralds would announce the new amounts, and allies could come to Athens to plead their case before a specially constituted court should an amount prove too much. Final decisions would rest with the Athenian Boule (Council or Senate).

Tribute for the Island District increased from a pre-war amount of 63 talents to 150 talents; Thrace increased from 120 talents to approximately 325 talents; the Hellespont from 85 talents to approximately 375 talents; and Ionia-Caria from 110 talents to 500 talents. These increases show no pattern or scale and seem to reflect simply a determination of resources available.

The Athenians also made additional demands for allied contingents and further included poleis that had not paid tribute for years as well as added others who had never appeared on the Tribute Lists. In no year before the start of the Ten Years War do the Delian League Tribute Lists record more than 180 poleis. The assessment of 425 BCE name no less than 380 and possibly more than 400 poleis now comprising the Delian League. Perhaps most ominously, however, the decrees threaten penalties at every turn. As Cleon had observed, the Athenians now ruled the Delian League as a tyranny.

SEVENTH YEAR OF WAR: 424/3 BCE

The following year, Athenians embarked on a more aggressive campaign. A Delian League force of Milesians, Andrians, and Carystians invaded Corinth, which marks the first explicit recorded use of League land troops. 60 triremes, 2,000 hoplites with cavalry, as well as 2,000 Milesian hoplites and other allies also attacked and captured Cythera. Cythera was an island in a strategic location off the Peloponnese. Athens forced Cythera to join the Delian League, and this further alarmed the Spartans.

The Spartan Brasidas, however, led 700 helots with 1,000 Peloponnesian mercenaries and repelled an Athenian attack on Megara. The Athenians managed to hold Nisea, but without Megara the Athenians could not stop an invasion from the Peloponnese. Athens further suffered a decisive loss at the Battle of Delium, and Athenian attempts once again to secure Boeotia and check the power of Thebes failed.

THE THRACIAN CAMPAIGN

The Spartan Brasidas, an atypical Spartan who displayed imagination with his courage, who could talk as well as fight, then led his force north through Thessaly (using skillful diplomacy) and into Thrace. The situation in Thrace had changed little since 429 BCE. Upon arrival in the north, Brasidas secured the (limited) aid of Perdiccas. He took Acanthus, Stagirus, Argilus, and then Amphipolis – strategically and economically the most important polis and the base of Athenian influence in the region.

Thucydides, son of Olorus, the historian, sailed from Thasos with his fleet of seven triremes but arrived too late to save Amphipolis. He successfully repulsed Brasidas' subsequent attempt, however, to take Eion. Myrcinus, Gelepsus, and Oesyne immediately rebelled from the Delian League, followed shortly thereafter by the whole of the Acte peninsula except Sane and Dium. Brasidas besieged Torone. After taking the polis, he requested reinforcements from the Peloponnesians while constructing triremes at Strymon.

At the end of the seventh year, the Delian League treasury had shrunk to 596 talents.

EIGHTH YEAR OF WAR: 423/2 BCE

By 423 BCE, news of Brasidas' actions in Thrace and the growing number of revolts they produced compelled Athens to act. The Athenians feared Brasidas might gain control of the Hellespont. They prepared forces to recapture and crush the rebellions near the Strymon river. Fortunately for Athens, the Spartans refused Brasidas' request for reinforcements because they "preferred to recover [the Spartans, who surrendered at Sphacteria] and put an end to the war" (Thuc. 4.108.7). They concluded a one-year truce with the Athenians to negotiate a more lasting peace.

![Greek Hoplites [Artist's Impression]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/4820.png?v=1741821138)

Although Scione and soon Mende revolted from the Delian League, Brasidas' campaign near Macedon nonetheless revealed that support for 'liberation' in Chalcidice proved neither resolute nor unambiguous by this time. The Greeks of Chalcidice remembered Sparta's failures from 446 and 427 BCE, the Thirty Years Peace, and at the revolt of Mytilene. The arrival of a Delian League force at Mende (40 Athenian and 10 Chian triremes with 1,000 Athenian hoplites, 600 archers, 1,000 Thracian mercenaries, as well as some light armed troops from various members of the League) immediately resulted in civil war, and the populace turned on the Peloponnesians. The Athenians then began a siege of Scione and further rebellions failed to spread.

After eight years of war, some Greeks felt freedom from Athens simply meant subservience to Sparta. The Delian League now had 444 talents in the reserve.

NINTH YEAR OF WAR: 422/1 BCE

The Athenians, after hearing the Delians sought an alliance with Sparta, ejected them from their island. They also elected to send 30 triremes, 1,200 hoplites, 300 cavalry, as well as a larger force of Lemnians and Imbrians, under the command of Cleon to recover the rebelling poleis about Thrace and including Amphipolis. Cleon recaptured Torone and established a base at Eion before Brasidas could return. The Stagirians repelled the Athenians, but Cleon successfully captured Gelepsus while Brasidas went to Amphipolis. Cleon would go on to recover several other rebellious poleis in the region.

Soon thereafter, Cleon and Brasidas, the two primary obstacles to a cessation of hostilities between Athens and Sparta, died at the Battle of Amphipolis (422 BCE). Their deaths opened a door for peace negotiations between Athens and Sparta. While direct talks commenced, the Athenians had already retaken Mende with little loss of life. They permitted the polis to re-enter the League with little difficulty. Scione, on the other hand, the last polis to capitulate the following year (420 BCE), suffered the original fate declared for Mytilene: mass executions and enslavement, and the Athenians then settled Plataeans there. The Greeks would remember the Athenian butchery of the Scionaeans well into the 4th century.

This article is part of a series on the Delian League:

- The Delian League, Part 1: Origins Down to the Battle of Eurymedon (480/79-465/4 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 2: From Eurymedon to the Thirty Years Peace (465/4-445/4 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 3: From the Thirty Years Peace to the Start of the Ten Years War (445/4–431/0 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 4: The Ten Years War (431/0-421/0 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 5: The Peace of Nicias, Quadruple Alliance, and Sicilian Expedition (421/0-413/2 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 6: The Decelean War and the Fall of Athens (413/2-404/3 BCE)