Daily life in the Inca empire was characterised by strong family relationships, agricultural labour, sometimes enforced state or military service for males, and occasional lighter moments of festivities to celebrate important life events in the community and highlights in the agricultural calendar.

The Family & Ayllu

The family was a fundamental component of Inca society, and strong attachments were made between even distant relations, not just close family. For example, the words for father and uncle were the same, as were mother and aunt, and the word for cousin was the same as brother and sister. Naming conventions illustrate that the male line was regarded as the most important by the Incas.

The wider family would all have been members of the same kin group or ayllu. Some of these, composed of hundreds of small family units, were large enough to be categorised as a subtribe. Marriage outside of this group was unusual so that all members of the ayllu were, in practice, related. They believed they came from a common ancestor, usually a legendary figure or even a mythical animal. Ancestors were often mummified and revered in regular ritual ceremonies. A further collective identity besides blood was the fact that an ayllu owned a particular piece of territory and the elders parcelled it out for individual families to work on so that they might be self-sustainable.

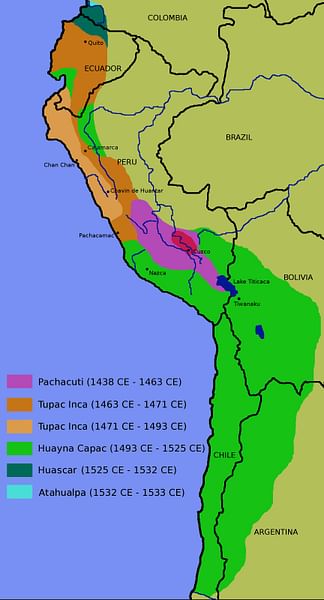

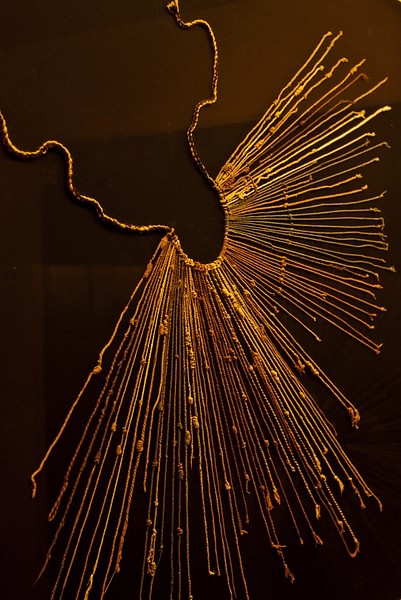

The ayllu system of social governance was much older than the Incas themselves, but following their conquest of local tribes they used its conventions – for example, common labour in the service of the ayllu chief or chiefs and role as a political and trading body for relations with other ayllu – to good effect to better govern their empire. The Incas also put greater emphasis on the geographical ties between individuals and introduced a new aristocratic class which could not be accessed from a lower social group through marriage. Even new ayllus were created (each Inca king created his own, and forced resettlement was another reason), and above all, warriors now no longer pledged allegiance to the leader of their ayllu but to the Inca ruler at Cuzco. In the same way, the worship of particular local deities by any one ayllu was permitted to continue, but these were made subservient to the Inca gods, especially the sun god Inti. Finally, the Incas kept precise census records using their quipu (khipu) devices of knotted-string, in which males within the empire were classified according to their age and physical capacity for work in mines, fields, or the army.

Several of these cultural changes under Inca rule may well have been factors in the empire's collapse following the European invasion and explain many communities' readiness to join forces with the conquistadores against their Inca overlords. With distant leaders, imposed tribute and religion, and a feeling of isolation and anonymity in the vast Inca empire, the traditional ayllu with its close ties between individuals, a common heritage, and familiar leadership must have seemed a much more preferable way of life.

Birth

As with most ancient (and perhaps many modern) cultures, the events, besides warfare, when Inca communities had most opportunity to reinforce shared cultural practices and personal ties were births, marriages, and funerals. Again, common to ancient societies, births and deaths were high, especially the infant mortality rate. Families in ancient Peru on average had five members. There was no birth control (or infanticide), and children of both sexes were welcomed so that they might assist the family working the fields. Pregnancy did not interrupt a woman's agricultural duties, and when she gave birth, there was no help from a midwife. Babies were kept in a wooden portable cradle that the mother could carry while she worked.

Once weaned, a feast (the rutuchicoy) was held at which the baby was named, given gifts, and clippings of its nails and hair were kept aside. The child was instructed in all it needed to know by its parents as there were neither schools nor a writing system and they were expected to help their parents as soon as they could walk. For this reason, most children would have learned the trade of their parents. Children of the nobility at Cuzco did, however, receive some formal instruction concerning Inca religion and history, the quipu, and warfare. A select number of girls were chosen as future priestesses and trained in religion, weaving and the cooking of special dishes and preparation of chicha beer for religious feasts.

Puberty

Puberty was an important passage for both boys and girls. The latter had a feast in their honour and were given gifts and their name (by their most senior uncle) to be used for their adult life. Boys had a more communal rite of passage involving races and sacrifices when their ears were pierced in order to wear the earspools of Inca rank. Here too, they were given a new adult name. There were no surnames in Peruvian society, and first names could be anything that best described the individual, leading to such names as 'Condor' (Kuntur), 'Jaguar' (Uturunku), 'Star' (Cuyllor), 'Gold' (Qori), and 'Pure' (Ocllo). Children of the elite would have carried several other names and titles depending on the rank and deeds they achieved through life.

Marriage

The next big event in a young person's life was marriage. This probably took place when the couple were in their teens, although chroniclers disagree on the matter. A male was not considered an adult until he had married. As in any agricultural economy, it was not economically feasible for a person to remain single, and for the same reason, divorce was unheard of, at least formally speaking. The choice of partner seems to have been largely up to the individuals concerned in consultation with their parents. When the father of the girl accepted the traditional gift of coca leaves from the boy, the deal was done. The wedding ceremonies were not held for individual couples but perhaps once annually for all those getting married in a particular ayllu. In some areas, there was also the possibility of trial marriages where the couple lived together for a short period before committing to the full obligation of marriage. As virginity was not particularly prized in ancient Peru, the girl did not suffer any reputational repercussions, at least in that respect, from failed trials.

After the non-religious ceremony of feasting and gift exchange, the bride moved into the area of her partner's family in a new home and worked that land alongside her husband which he had inherited at birth. The quantity of land the bride had inherited (half the size of that given to males) was given back to the ayllu's communal lands. The family home was a simple affair of mud-brick or beaten mud walls with a thatch roof, a single low door and no windows. Inside was a central hearth and beds were made from llama skins. The living space was divided into two areas: one for sleeping and the other for cooking and keeping domestic animals such as guinea pigs.

In a culture where frequent wars meant that the male population was significantly smaller than the female, polygamy was permitted, although it seems to have been restricted largely to the aristocracy for whom it was also common to have many concubines. The first wife was always the most senior if there were secondary wives. A widower could remarry anyone he chose, but a widow could only marry her husband's brother.

Working Life

Both sexes worked in the fields using simple tools, and often in teams, or they raised livestock or fished and hunted, depending on their location. Men might be required to perform labour duties (building and maintaining Inca roads or farming on Inca state lands) or military service to the Inca rulers. When this happened and men were called away, their neighbours helped out so that the family farm could continue to function.

Women were expected to prepare the meals, care for the children, and perform such needed tasks as cleaning and weaving. The latter provided camelid-wool clothes, usually only one set for each member of the family. Regarding clothes, when worn at all, men wore trousers (huara), a sleeveless shirt (cushma or uncu), and, if necessary, a woollen cape (yacolla). Women wore a long belted tunic (anacu) and a yacolla, too. Footwear, if worn at all, was in the form of leather and woollen-cord sandals (usuta). Besides weaving other crafts might have been done, most typically pottery, which was made by both sexes.

Probably meal times were the most anticipated daily events, once in the morning and again in the evening, with wood or llama dung being the most common fuels. Diet was largely vegetarian with meat being reserved for special occasions, although coastal communities would have had access to seafood. Quinoa porridge, maize, and potatoes were staples, wild fruits were readily available ranging from sour cherries to pineapples, and treats included popcorn.

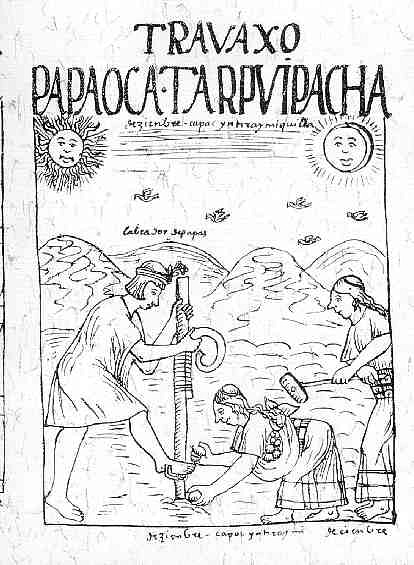

Both sexes would have participated in public religious ceremonies and in festivities related to the agricultural calendar, where drinking chicha beer would have been a highlight. Dancing was an important feature of the festivities when dancers mimicked activities such as hunting, sowing, or battles. Musical accompaniment came from ceramic panpipes, drums, bells, clackers, rattles, tambourines, and seashell trumpets. Leisure activities seem to have been few and far between, but there is evidence of sports such as running and jumping, boardgame-playing, and gambling using dice. Poetry recitals, recounting myths and singing traditional ballads were other popular pastimes.

Death

Ancestor worship was an important part of ancient Peruvian culture. Individuals were mummified and carefully stored so that they might be brought out again in regular public ceremonies. Mummies were set in a foetal position and wrapped in fine textiles if the family could afford it. The possessions of the deceased and the tools they used in life were also buried with them or, on occasion, burned in ritual. The funeral ceremony might last a week, and in the case of the nobility, the individual's lesser wives and servants were sometimes sacrificed to accompany the body into the next life. Mummies were either buried in graves or placed in caves. Children who did not reach adulthood were often buried in pottery urns. A period of mourning was observed (up to a year for the elite at Cuzco) during which black clothes were worn and women covered their heads. A man could not remarry within one year, sometimes even two, of the funeral ceremony of his first wife. The tombs of the deceased were regularly reopened to offer food and drink to the mummies or to add new occupants.