This text is part of an article series on the Delian League.

The sixth and last phase of the Delian League begins with the Decelean War, also referred to as the Ionian War, and ends with the surrender of Athens (413/2 – 404/3 BCE). The final nine years of the Delian League became the most chaotic for the alliance as a whole. It suffered repeating reversals in fortune, while actual control of the Delian League at times shifted between the polis of Athens and the Athenian fleet operating in the Aegean. Although the two hegemons made peace in the spring of 421 BCE, that peace had effectively ended in late summer of 418 BCE, when an Athenian contingent fought alongside Argos and Mantinea against Sparta during the summer of 418 BCE. We possess limited evidence, but the assessment of 421/0 BCE also shows the Athenians dispositions changed little since the assessment of 425 BCE.

Under the advice of Alcibiades, who had defected to Sparta after fleeing from Sicily, King Agis seized Decelea (413 BCE). Decelea rested 14 miles (c. 22 km) north-northeast of Athens. A permanent Peloponnesian garrison deprived Athens of all territory outside the walls as well as access to Euboea. 20,000 slaves, many of whom worked the nearby silver mines, deserted the polis. Thebes promptly confiscated most of the abandoned material and supplies in the Attic countryside. The Athenians again responded with 30 triremes and a force of Argive hoplites to raid the Laconian coast. Moreover, the Delian League had small forces operating in the Thermaic Gulf and in Ionia. Even with the bulk of the Athenian fleet engaged in Sicily, the evidence shows Athens suffered no widespread discontent with its allies in the Aegean at this time.

THE DISASTER IN SICILY

As King Agis prepared his fort, the Peloponnesians readied additional reinforcements for Syracuse: 25 Corinthian triremes with numerous troop carriers; 600 Helots; 500 Corinthian, 300 Boeotian, and 200 Sicyonian hoplites, as well as a number of Arcadian mercenaries. They slipped past the 20 Athenian triremes at Naupactus. When word of Nicias' troubles in Sicily reached Athens, the Athenians readied even further League reinforcements of their own: 60 triremes, 5 Chian ships, 1,200 Athenian hoplites with additional allied soldiers. This force, however, paused to assist on the Laconian raids then seize and fortify the isthmus of Cythera. The reasoning remains unclear, and they realized little in return. The fleet then stopped to collect addition allied forces from Zakynthos, Cephallenia, Messenians, as well as Arcarnanians.

After leaving ten vessels to assist Corcyra, the fleet finally proceeded to Sicily. By the time they arrived, however, the allied situation had thoroughly deteriorated. The Syracusans, aided by Peloponnesian arrivals, drove the Delian League forces to the defensive. Although the sources attest to certain defections amongst some allied soldiers, the allied contingents as a whole remained loyal. Even during the final retreat, the majority of them refused to surrender or defect. Nevertheless, the Syracusans and Peloponnesians routed and destroyed the entire Delian League force at the Assinarus river.

AFTERMATH OF THE SICILIAN EXPEDITION

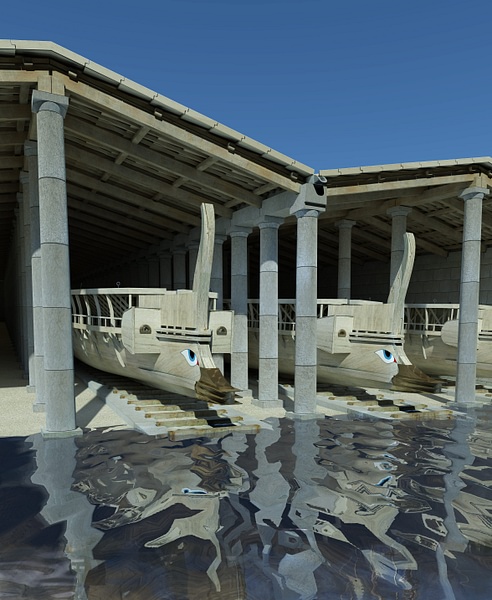

When word of the catastrophe first reached Attica, no one, in fact, believed the initial reports. Nevertheless, the disaster in Sicily utterly decimated Delian League resources and thus crippled the power of Athens. Disbelief soon morphed into anger, which then turned into terror. The Syracusans and Peloponnesians had destroyed or captured at least 216 triremes – 160 of them Athenian. Athens also lost 3,000 Hoplites, 9,000 thetes, and thousands of metics. The city now possessed no more than 100 triremes in the Piraeus docks, all suffering from differing stages of disrepair, and almost no treasury to complete the needed repairs or hire more crews.

The Tribute Lists, in fact, show the Delian League had but 444 talents on hand, though it still collected approximately 900 talents annum by this time. Now, however, it had no fleet to enforce those collections. Moreover, the Spartan army at Decelea penned the Athenians in the polis and deprived the Athenians of their mines and farming land. Several allies soon competed fiercely to revolt first: Euboea, Chios, Lesbos, Rhodes, Miletus, and Ephesus. The Spartans calculated they could now depose Athens and "safely hold hegemony of the Hellenes" (Thuc. 8.2.2-4). The Delian League, it seemed, threatened collapse.

The Athenians, however, became determined to do what they could. They first elected a board of ten elders to advise and temper passions of the Ekklesia. They took all required steps to secure timber, prepare a new fleet, see to the alliance, and would consider tapping the League 'iron' reserve of 1,000 talents while reducing public expenditures. They abandoned the fort in Laconia and constructed one at Sunium to protect imported grain shipments from the Spartan garrison at Decelea.

REORGANIZATION OF THE DELIAN LEAGUE (AGAIN)

Additionally, the Athenians instituted the most sweeping logistical change attempted to finance the Delian League: they canceled tribute assessments, which had taken on a considerably negative connotation by this time, and instead imposed a 5% levy on all import-export goods transported by sea (413 BCE). This new system of financing the alliance would result in greater revenue but required more detailed control of collection. Confident of a bureaucracy in place for over 60 years, the Athenians thought themselves up to the task. Evidence shows, however, they met with varying and limited success. Although they never officially rescinded the tax, they reinstated tribute for at least some members of the League by 407 BCE.

Despite this resurgent Athenian determination, Sparta seemed poised for victory (412 BCE). King Agis had reestablished the colony at Heraclea and forced the Achaeans as well as other allies of the Thessalians to surrender hostages. Euboea, Lesbos, Chios, and Erythrae all offered assistance in return for Spartan support. The Decelean War, unfortunately for the Peloponnesian League, would now shift to the east Aegean.

THE PELOPONNESIAN LEAGUE & PERSIA

The Spartan alliance still proved poorly adapted to sustain overseas operations. Sparta lacked ships, experienced naval commanders, and, most importantly, financing. The Peloponnesian League had no consistent income and no reserves. A large, ready fleet required crews, who needed to be paid regularly. Regular pay required regular subsidies. The Spartans, in fact, managed to launch only 39 triremes.

To meet the financial limitations, the Peloponnesian League turned to Persian money. Although the overtures met with hesitation, opportunism, and even suspicion, the Spartans would eventually negotiate three treaties with the Persian King. Persia's attention, however, remained divided between two rival satraps: Tissaphernes at Sardis wanted to concentrate the war in Ionia, while Pharnabazus at Dascylium wanted to concentrate efforts in Caria – and both wanted the credit for recovering those Greek poleis the Persian Empire lost to the Delian League following its second failed invasion.

What immediate tactical advantages Sparta enjoyed also revealed an inherent underlying strategic weakness. Euboea and Lesbos had appealed to King Agis at Decelea, while Persia, Chios, and Erythrae sent to Sparta directly and made their cases to the Ephors. Because these two centers of power had long-standing rivalries and often suffered disagreements, it took months for Sparta to formulate any consistent policy. The Peloponnesian League, again under the advice of Alcibiades, eventually voted to sail for Chios to establish an eastern base of operations, and, from there, incite rebellions in the region, but they delayed the departure.

THE AEGEAN & IONIAN WAR (412 BCE)

The Athenians, with Macedonian timber, began hobbling together a new navy, and, after intercepting the first Spartan fleet to sail for Chios, chased the Peloponnesians to the deserted fort of Spiraeum, just north of Epidaurus. They destroyed the Peloponnesian ships. The Athenians then blockaded the passage, cutting off Corinthian ships from the Aegean. A small Spartan fleet of 5 triremes, again on the advice of Alcibiades, slipped passed the blockade and arrived in Chios, which resulted in an open rebellion. Erythrae joined in revolt and soon discontent spread to Clazomenae, Lebedos, Haere, Anea, and Ephesus. Miletus, the jewel of the Aegean, followed. The Spartans now commanded 23 triremes in the area.

Athens soon responded. The two already deployed Athenian fleets chose to anchor at Samos. The force numbered 28 triremes. 19 ships departed to intercept the Peloponnesian fleet at Miletus but arrived too late; they turned to Lade, where they blockaded the Milesians, while a Peloponnesian force of 13 triremes brought Methymna and Mytilene into rebellion.

The Athenians elected to tap the "emergency [iron] reserve" and build even more ships (Thuc. 8.19.3-4). Meanwhile, a reinforcement fleet of 16 Delian League triremes arrived at Samos, followed shortly thereafter by a force of ten triremes. This now sizeable Athenian fleet prompted Samos to erupt in a ruthless revolution. The new faction established a strong democracy. The Athenians, in turn, granted them independence. With Samos now a secure base of operations for the deployed Delian League fleet, the Athenians set out to reverse the losses suffered.

The Peloponnesians, meanwhile, broke through the blockade at Spiraeum. Four ships made it to Chios. They landed at Lesbos during the same day the Athenians had arrived with 25 triremes. Though the Spartans convinced Phocaea and Cyme to revolt, the Athenians defeated the Chian fleet in harbor, won a pitched land battle, and captured the main polis of Lesbos in short order. The Athenians then retook Clazomenae and sailed toward Chios. They landed at the Oenessae islands, where they initiated a blockade and conducted raids. The Athenians had now successfully blockaded the two major poleis in the region: Chios and Miletus. Later in the year, further Athenian reinforcements of 48 ships (triremes and troop carriers) arrived at Samos bringing with them 3,500 hoplites: 1,000 Athenian; 1,000 Aegean; and 1,500 Argives. This force soon laid siege to Miletus (412 BCE).

Peloponnesian reinforcements, in turn, landed on Leros: 33 ships supplemented by 20 Syracusan and 2 Selenian triremes. The Athenians abandoned the siege, which angered the Argives, who returned home, while the Peloponnesians surrendered Iasus to the Persian Satrap Tissaphernes. 12 additional triremes from Thurii, Laconia, and Syracuse would arrive later at Knidos, which Tissaphernes had already incited to rebel from the Delian League. While Sparta recognized Persian claims to the Greek poleis of Asia, the Spartans had not consulted those Greeks. Sparta's agreements with Persia made a mockery of the liberation Sparta once promised. Athens, meanwhile, allied with the poleis resisting Persia against Tissapehernes.

ALCIBIADES IN PERSIA & THE SEIGE OF CHIOS

Athens' recovery but one year after their disaster in Sicily proved nothing short of extraordinary. At the same time, the Spartans grew suspicious of Alcibiades. He seemed too clever for them; they resented his vanity, came to mistrust him, and ordered him killed. Alcibiades, realizing he had lost Spartan confidence, fled to Sardis and began advising Tissaphernes. Alcibiades, who now actually desired to return to Athens, convinced Tissaphernes to become dilatory and evasive to the point of frustration with the Spartan leaders. Tissaphernes cut their pay and then paid irregularly. The Satrap also withdrew all direct military support to encourage the Delian and Peloponnesian Leagues to fight each other and thus deplete their resources.

That winter, the Peloponnesian fleet, now numbering 80 ships, lay idle at Miletus, while further Athenian reinforcements of 35 triremes arrived at Samos. The Delian League now had 104 ships in the Aegean. The remainder of the Peloponnesian fleet, anchored at Chios (16 triremes), attempted various raids on the neighboring coastline but accomplished little. The Athenians, on the other hand, elected to deploy their fleet: 30 triremes to Chios and 74 to Miletus.

The Spartans remained divided. The Spartan governor of Chios and their naval commander disagreed on whether or not to assist Lesbos in its rebellion from the Delian League. The Peloponnesian force at Knidos separated into two contingents: one to protect the polis and another to conduct raids on shipments from Egypt. The Athenians, meanwhile, built a fort on Chios. The Spartan fleet at Miletus refused to intervene. Meanwhile, an additional Spartan fleet of 27 triremes arrived at Caunus. After a brief skirmish between a Peloponnesian fleet of 64 ships sent from Miletus and an Athenian fleet of 20 ships sent from Samos, the Spartans brought their now combined fleets of 94 ships to Syme and later proceeded to Calirus on Rhodes. The Athenians, meanwhile, completed their fortifications on Chios, and the island began to suffer a famine (411 BCE). The Spartans would have attempted to relieve the blockade but still feared an open naval battle against an Athenian fleet and thus retired back to Miletus.

Sparta's new treaty with Persia abandoned Ionia, and the Spartans turned to Abydos in the Hellespont. It soon rebelled from the Delian League followed shortly thereafter by Lampsascus, but the Athenians soon recovered it. At the same time, a Peloponnesian fleet of 35 triremes, including 5 from Thurii, 4 from Syracuse, and 1 Anaean, fought an Athenian fleet of 32 vessels, which included troop ships, to a draw.

THE FOUR HUNDRED & THE FIVE THOUSAND (411 BCE)

By 411 BCE, the blunders of the Athenian democracy had fostered growing discontent among the oligarchic-minded Athenians. Athens' policies appeared foolish, their executions incompetent. The League fleet, operating out of Samos, furthermore, failed to recover Miletus and rebellions had now spread to the Hellespont again. These results threatened the Athenian lifeline from Euxine.

Athens suffered two brief oligarchic revolutions: The Four Hundred followed shortly thereafter by the Rule of the Five Thousand. The Four Hundred immediately entered into negotiations with the Persian satrap Tissaphernes as well as the Spartan King Agis. The new regime further pledged to secure the League with similar oligarchies, but the Athenians of the League fleet stationed at Samos refused to recognize the revolution.

Those Athenians called an assembly on Samos to debate the situation. They listened to the recently recalled Alcibiades. The fleet had become enraged and desired to sail immediately to Piraeus and attack Athens, but Alcibiades encouraged them to hold fast with hopes of securing the aid of Tissaphernes. The Argives, furthermore, dispatched representatives to Samos, proclaiming that Argos recognized the Athenians on the island as the true polis. The navy, in effect, had created a second Athens. These Athenians consolidated their forces and, under the leadership of Alcibiades, ended their internal divisions.

The Four Hundred, meanwhile, suffered an uprising in Piraeus when word spread that they would rather betray the polis to Sparta than surrender to the Athenians on Samos. The Spartans readied a fleet of 42 triremes, reportedly to help Euboea revolt against the Delian League, but whose true motive appeared rather to sail to Eetionia and, from there, attack Piraeus. The Piraeus uprising, however, coalesced into the rule of the Five Thousand and successfully mounted a defense of Piraeus. The Five Thousand then dispatched a fleet of 36 triremes to attack the Spartan fleet, which had sailed on to Euboea. The Athenians lost 22 ships, and the island revolted. The Spartans, however, failed to pursue the advantage and did not move to attack Piraeus.

THE WAR IN THE AEGEAN CONTINUES

The Spartan forces stationed on Miletus, moreover, while growing in number and resources, still suffered from discord, division, and indecision and accomplished little. Athens "could not have had a more convenient enemy" (Thuc. 8.96.5). The Delian League dispatched a number of triremes to collect tribute and recapture the Hellespont. They recovered Lesbos and Mytilene while further fostering a civil war in Thasos (411 BCE). Athenian commanders secured additional victories in the area, suppressed the possibility of any further wide-ranging revolts, and by the end of the year had over 100 triremes at sea.

In addition, Knidos, who voluntarily seceded to Persia, now drove out its Persian garrison in a sudden reversal of disposition. Moreover, the Milesians drove out its own Persian garrison. Persia, in the meantime, commissioned a fleet of 147 ships to aid the Peloponnesian League, which arrived at Aspendus, but it never entered the Aegean. Whether or not the Persians followed the advice of Alcibiades, who still advocated letting the two Leagues drain their resources against each other, or the Persian King became more concerned with unrest in other parts of the empire, remains debated amongst scholars.

Additionally, Corinth offered Sparta little direct aid while Megara appeared interested only in helping its own colonies Byzantium and Selymbria break away from the Athenian alliance. Boeotia, whose attention remained primarily on the Greek mainland, also contributed little to the east Aegean. The mixed crews that the Spartans now commanded, furthermore, proved far more difficult to control than Spartan hoplites. These commanders also encountered a tough streak of independence from their Syracusan and Thurian allies.

DIVIDED LOYALTIES

More importantly, however, the sheer size and age of the Delian League exposed competing underlying loyalties among its many members. In addition to the broad affinities Ionian Greeks naturally held with Ionian Athens and Dorian Greeks possessed with Dorian Sparta, the Athenians had also spent 60 years fostering and establishing democracies throughout the Aegean. Sparta, on the other hand, favored oligarchies.

Oligarchs of each polis saw in Sparta the hope of gaining power, while the masses naturally looked to Athens. Most of the poleis, which broke away from the Delian League, did so because oligarchs seized power. The democrats, however, often remained loyal to Athens. While these democrats would have certainly preferred a free democracy to a subject democracy, a subject democracy proved far superior to an uncontrolled oligarchy, and thus they resisted Spartan 'liberation.' The Athenians discovered they faced weaker enemies and still possessed more friends than they had first realized after the disaster in Sicily.

THE BATTLE OF CYZICUS

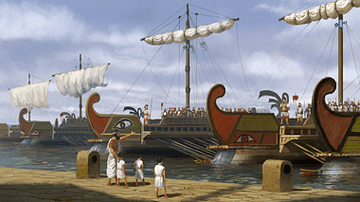

The embarrassing lack of consistent aid from Tissaphernes eventually drove the Spartans to abandon the satrap and ally with Pharnabazus, whose aid proved resolute and consistent. After the revolt of Chios, the Spartans now commanded a fleet of 112 ships. They sent 26 triremes to Byzantium and 13 to Rhodes. The Peloponnesian League successfully incited rebellions in the areas. Consequently, the Athenians on Samos dispatched several triremes to meet the threats. Athenian commanders sought to recover poleis and collect levies where they could. Then, under the leadership of Alcibiades, the League eventually reassembled the entire fleet in the Hellespont. The Peloponnesian and Delian League navies finally clashed in the Propontis at Cyzicus, where the Spartans lost anywhere from 135 to 155 ships (410 BCE). ![Greek Trireme [Illustration]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/154.jpg?v=1739953088)

In spite of unprecedented Spartan efforts at sea, and belated but ultimately reliable and consistent support from Persia, as well as two back to back revolutions in Athens in addition to the Athenians lacking immediate funds, the Peloponnesian League experienced nothing but a string of losses and setbacks in the Aegean. Moreover, even though the Spartans still controlled Decelea on the Greek mainland, and Rhodes, Miletus, Ephesus, Chios, Thasos, and Euboea, as well as a handful of poleis on the Thracian coast and in the Hellespont, the Athenians again controlled the Aegean Sea and, with it, the bulk of the Delian League. The Peloponnesian League, furthermore, suffered the loss of important support when Carthage invaded Sicily, and the Syracusans withdrew. Sparta thus made overtures to secure a peace and stabilize the positions reached. Athens' now restored democracy, however, refused.

DELIAN LEAGUE LOSSES & ATHENS RECOVERS THE AEGEAN

The Delian League soon lost its important ally Corcyra after a civil war erupted in 410 BCE. They then lost Pylos in 409 BCE, an important base for operations against the Peloponnese. The League also lost Nisaea in Megara to a rebellion. In addition, a small Spartan fleet of 25 ships captured Chios. Although these represented irritations, the Athenians still maintained overall control of the sea. More ominously, however, Pharnabazus provided Sparta with the money to build a fleet as great as the one destroyed at Cyzicus. The Athenians, in the meantime, dispatched reinforcements to Samos, and, from there, they sought to recapture Pygela but failed. The League fleet then ravaged the countryside for some time, but the Persians eventually drove the Athenians back to the coast.

The Delian League began to gain the advantage, however, when Alcibiades recaptured Selymbria in 408 BCE. The Athenians installed a garrison and extracted tribute. Thrasybulus then recovered Thasos in 407 BCE. Despite the initial setbacks, the Delian League soon recovered the Hellespont, and the Athenian fleet could sail and raid at will by 407 BCE. Alcibiades thus sailed about the Ceramic Gulf and collected 100 talents throughout Caria. This good fortune Athens experienced, however, would not last.

DEMISE OF THE DELIAN LEAGUE

The Athenians welcomed Alcibiades home and elected him to full command by land and sea. At the same time, the Spartans had embraced their ablest leaders to date: Lysander and Callicrates. Even though these two Spartans had become rivals, they both proved to possess what previous Spartans commanders since Brasidas had lacked: initiative, daring, shrewdness, and inventive thinking.

After an embarrassing minor loss at Notium against Lysander (406 BCE), and even though the League suffered few casualties and still commanded an impressive fleet of 108 triremes, Alcibiades' rival demagogues in Athens discredited him, and he fled Athens for the last time. It appears Lysander made use of the opportunity Notium presented to offer more pay and a not insignificant number of League rowers deserted the fleet at Samos. The new Athenian leader, Conon, arrived to find he had crews to fill only 70 ships.

BATTLE OF ARGINUSAE & THE EXECUTION OF THE GENERALS

While Conon continued to sail, collect tribute, and suppress rebellions where he could, Callicrates launched a campaign with 140 triremes, which soon grew to a force of 170. He attacked those poleis under Athenian control and put an end to Conon's "adulterous affair with the sea." He then successfully blockaded the League fleet at Mytilene. The Athenians managed to equip 110 additional triremes: 60 Athenian and 50 from the islands (Xen. Hell. 1.6.24; cf. Diod. 13.97.1). Then, after collecting 10 warships from Samos and 35 more from additional League members, this relief fleet sailed for Mytilene. When Callicrates received word of the reinforcements, now numbering 145 triremes, he dispatched 110 of his triremes to intercept.

The Battle of Arginusae proved the largest battle ever fought between Greek navies, and the Peloponnesian fleet once again suffered a decisive defeat, losing just under 80 ships. The Athenians, however, fatally squandered the victory by collectively executing their ablest commanders for failing to recover bodies from 12 wrecked triremes of the 25 they lost during the battle. Never before in Athens' history had the Athenians executed a military leader, let alone six in a single act. The trial and deaths divided the Athenians, and the death sentences made finding good leadership extremely difficult at a time when such leadership became paramount for the survival of the Delian League.

BATTLE OF AEGOSPOTAMI & THE SIEGE OF ATHENS

Even though the Peloponnesian League still deployed over 90 ships, they again sued for peace, but the Athenians again rejected the offer. They commanded a force of up to 180 triremes in the Aegean, and it stood free to raid and plunder island and mainland poleis friendly to Sparta. Sparta thus dispatched Lysander with 35 triremes. He promptly assembled the entire Peloponnesian fleet at Ephesus and, from there, sailed to Miletus and on to Caria, leveling and subjugating poleis as he went (406/5 BCE). He eventually made his way back to the Hellespont. Lysander's arrival again threatened the Euxine lifeline, compelling the Delian League fleet to follow. The Athenians and their allies lost 168 of their 180 triremes in the decisive and final engagement at Aegospotami.

With the Delian League fleet destroyed, Athens became utterly defenseless and prepared for the inevitable siege to follow. The Peloponnesians surrounded the polis, and the Delian League had no more money. Refugees jammed inside polis, soon began to starve, and Athens neared revolution again. Finally, the Athenians surrendered. The remaining poleis resisting the Peloponnesian League opened their gates, and the Spartans purged Delos of all Athenian influence. Sparta demanded Athens pull down its long walls, which for half a century had provided the polis protection against the Peloponnese and Boeotia. The Spartans also forced the Athenians to surrender the remainder of their fleet, except for 12 ships to serve as a police force, and to relinquish all overseas possessions – including the cleruchies. The Delian League ceased to exist.

JUDGEMENTS & CONCLUSIONS

The Delian League represents the largest and most successful Ancient Greek Confederation devised. It survived often surprising and numerous setbacks and calamities. The Confederacy of Delos also followed what became a predictable pattern with multi-poleis alliances: contributions from members first came freely but later needed to be collected by the hegemon under coercion, and, when decent spread, it resorted to interference, suppression, and repression. Calls for early Athenian hegemony resulted from the discrediting and indifference of the Spartans, but Greek moods often changed suddenly and quickly. Athenian leadership alone could not end rivalries or factions. Athens soon found it necessary to install garrisons and magistrates and eventually to impose Athenian laws upon its allies. At the Delian League's height, the Athenians deployed 700 overseas officials.

The Delian League indeed morphed from τὸ ξυμμαχικόν (a body of allies) to an Athenian ἀρχή (command or rule). All the independent member poleis first joined in common council (συνέδριον) but later simply took instructions from the Athenians. The allies thus went from αὐτόνομοι (independents) to ὑπήκοοι (subjects). A new word would enter the oaths of allegiance: πείσομαι (obedience). Despite the inherent differences between each of the poleis, all Ancient Greeks worshiped the same gods and spoke the same language. They farmed and fought in the same manner, and, while individual poleis adamantly protected their independence, they still thought of themselves as a single people.

Ancient Greek may not have a word for 'empire,' but the Greeks could express the idea of imperialism using paraphrases like ἀρχή + πολυπραγμοσύνη + πλεονεξία (a rule + much meddlesomeness and officious interference + an insatiable desire to have what rightfully belonged to others). The Athenians engaged all three practices. There perhaps exists no better commentary on the Athenian's rule of the Delian League and the imperialism it produced than Aristophanes' Birds, where a series of Athenians appear to protect then guide and finally to suppress the constitution-makers of Cloudcuckoobury.

The history of the Delian League shows the Athenian practiced their form of imperialism gradually. Athenian imperialism emerged from the League's successes, as a kind of economic and political subjection, a necessary coercive power over the other poleis of the alliance to ensure continuance. Athens' exploitation of the League's members, however, did not entail direct control of either the means or labor of production within those poleis. Whether or not this constituted an actual 'empire' lies beyond the scope of this article. While the allies could rightfully assert the Athenian democracy first looked to its own interests, they also could not deny it remained loyal to its friends. Samos, for example, had become independent during the Decelean War, and, when Alcibiades took Byzantium, he also found help from within the polis. When Lysander subsequently took Byzantium after Aegospotami, those men fled to Euxine but later went to Athens and became Athenian citizens.

By the start of the Ten Years War, nevertheless, Athens had indeed become a tyrant. Its rule of the Delian League had continued neither from the official acceptance of other members nor from any type of formal agreement. Nevertheless, most of the allies remained loyal until the end. Thucydides certainly never suggests that Athenian rule of the Confederacy rested on the allies' free consent, but the 4th-century orators never suggest that it did not. Regardless, the Athenians argued their rule existed as more moderate than others had in the past or would in the future: an interesting claim, since the 27-year strife that led to Athens' eventual surrender, and, with it, the Confederacy of Delos' demise, represents perhaps one of the most horrific civil wars in early recorded history.

The second and final nine-year clash between the Delian and Peloponnesian Leagues boasted, like the Ten Years War that preceded it, not only conventional land and naval battles but also terrorism, revolutions, assassinations, mass evacuations, and mass murders. Thousands died from combat, sieges, ethnic cleansing, droughts, famine, and plague. All of this calamity, moreover, unfolded alongside a baffling array of shifting alliances on the Greek mainland.

The professed aim of the Delian League began as a fight for freedom from the Mede, but that goal would change to advancing Athenian desires and fostering Ionian culture. Athens attempted to rule by Athenian Law, by promoting Panhellenism, and ultimately the Athenians sought to craft a monumental metropolis, which often meant cramming democracy down the throats of resistant poleis. The resulting civil war encompassed everyone in the Greek-speaking world. By the time it ended, 80,000 Athenians and countless other Hellenes had died and 500 ships had sunk throughout the Aegean and suffered destruction in Sicily.

The three greatest motive forces behind Athens' failure to lessen Delian League obligations became fear, pride, and profit. Fear caused the Athenians to rule the Aegean and fear further drove them to seek out Sicily and expand the League even further – not to reduce or subjugate those Greeks, they argued, but rather to save them from subjugation. Athens professed to fight for the 'Greek cause.' Without Athens, the Athenians held, the Aegean would fall to the Mede and Sicily to the Carthaginians.

Athens exploited the allies to achieve these goals to some extent, but it did not do so in any systematic or extensive way. The total tribute collected became quite large, but few individual poleis paid significant sums. Before the great wartime reassessment of 425 BCE, only 14 poleis paid more than 10 talents, and only 5 of those paid more than 15 talents. Fully understanding the actual burden these allies experienced goes beyond the extant evidence on their resources, but scholars doubt Athens required them to pay more than they could comfortably afford (at least until well into the Peloponnesian War). Some of them certainly came to see tribute as a symbol of subjection, but that remains another matter.

All Athenians profited in some way from ruling the Delian League. The poor gained land through the growth of colonies and cleruchies, while also receiving pay for naval and jury service. The rich gained land and achieved prominence through various public offices, which governing not only Athens but also the League required. All Greeks, but especially the Athenians, benefited as well from the increased maritime trade, and, while Athens increased its share of this trade, the volume of trade had also become considerably larger – but such advantages came at the loss of polis autonomy and at the cost of land confiscation as well as the general infringement of liberties.

The Delian League's achievements against the Persian Empire remained uncontested throughout Greece, but Athens also used Delian League resources to suppress and repress. These meddlesome acts directly assaulted the Hellenic sense of independent civic corporatism, which the very nature of the polis demanded. The Athenians came to overthrew oligarchies everywhere; the Spartans overthrew democracies.

An opportunity to revive another Athenian-led league would soon emerge when the Aegean grew disillusioned with Spartan hegemony. Sparta's championing the eastern Greeks against Athens and the Mede would prove desultory. The Spartans held that all Hellenic poleis, great and small, would remain autonomous but only if ruled by pro-Spartan oligarchies – and the Spartans spectacularly failed. Spartan leaders soon found they too needed to impose governors and boards to rule and, to finance expeditions, exact tribute as harshly as the Athenians. "The Lacedaemonians put more men to death arbitrarily in three months than [the Athenians] brought to trial in the whole course of [their] rule" (Isoc. 4.113). The Peloponnesians also left many poleis unaligned, confused, and ambivalent. Many suffered invasions, sacks, or fell impoverished.

The fall of Athens and the dissolution of the Delian League did not lead, as hoped, to a general liberation of the Hellenes but simply left many Greeks abandoned. Other Greeks came to believe they had simply replaced one Greek tyrant with another, one that seemed far more incompetent and indifferent to the 'Greek cause.' The masses of more and more poleis began to call for a new Athenian Hegemony. Within ten years of Athens' surrender, Boeotia and Corinth prepared to ally with Athens and Argos against Sparta. Whether or not Athens learned from the mistakes it committed ruling the Delian League would become evident with the founding of the Second Athenian League.

This article is part of a series on the Delian League:

- The Delian League, Part 1: Origins Down to the Battle of Eurymedon (480/79-465/4 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 2: From Eurymedon to the Thirty Years Peace (465/4-445/4 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 3: From the Thirty Years Peace to the Start of the Ten Years War (445/4–431/0 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 4: The Ten Years War (431/0-421/0 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 5: The Peace of Nicias, Quadruple Alliance, and Sicilian Expedition (421/0-413/2 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 6: The Decelean War and the Fall of Athens (413/2-404/3 BCE)