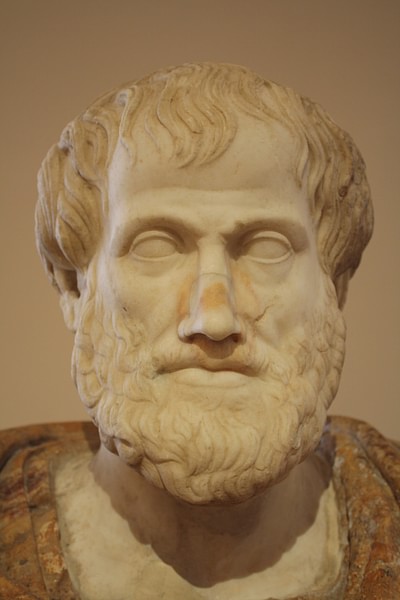

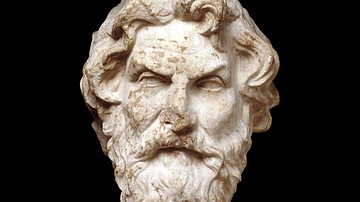

One of Aristotle's more famous quotes was, "All men naturally desire knowledge" ("πάντες ἄνθρωποι τοὺ εἰδέναι ὀρὲγονται φύσει") (Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1.980a.22). As a classical Greek philosopher, an ideology like this is required for producing many outstanding achievements. He was known as a philosopher, artist, and scientist. Greek-born, he started with humble beginnings by attending Plato's academy; becoming one of the most widely known philosophers in human history. Aristotle wrote many books, one of them was On the Heavens (ΠΕΡΙ ΟΥΡΑΝΟΥ). We are still not sure when the book was officially written, but it was around 350 BCE. His ideas included the four common elements on Earth (earth, air, fire, water), and also a fifth element which we will discuss later. The book revolves around his observations regarding the universe. The theories of Aristotle were groundbreaking for his time and were used until roughly the 1500s CE until the writings of Copernicus.

Nature of the Universe

The first main component to Aristotle's discussion is the nature of the universe. Aristotle concluded that three things make up a physically constituted entity: bodies and magnitudes, beings possessed of body and magnitude, and the principles of causes of these beings. Magnitude divided in one direction is a line, in two directions is a surface, and in three directions, a body. His view was much like our understanding today. We know a line (length) is one dimensional, a shape is two-dimensional (length & width), and most objects in our everyday life, including us, are three-dimensional (length, width, depth). This concept is over 2,000 years old.

He described the four elements of the world and nature - earth (heaviest), water, air, and fire (lightest) - and believed a fifth element existed (aether). To determine whether the body is light or heavy, Aristotle believed 'lightness' was the nature of moving away from the centre and 'heaviness' was the nature of moving toward the centre. The same goes for vertices; the lightest rises to the top, and heaviest moves downward. Aristotle was not the first person to propose the four elements. In the 5th century BCE, Anaximenes recorded the first proposal regarding the four elements making up everything. The elements, when combined, created qualities. Fire and Earth would make Dry; Water and Earth would create Cold; Water combined with Air would result in Wet; and finally, Air and Fire would be Hot.

Motion

Aristotle took it one step further with his observations of motion. Aristotle postulated that all bodies have a natural way of moving, which could be regular or irregular. He believed that everything that moved was moved by something. The latter is only possible when the irregularity of the movement proceeds from either the mover or from the object moved or both. Basically, this is saying bodies could naturally move in a straight line or not all. This idea is actually a rudimentary form of Newton's first law of motion (an object will remain at rest or in uniform motion in a straight line unless acted upon). He also introduced a third option which was circular motion.

Aristotle noted that the motion of the body moving upward would be fire or air, and downward would be water or earth. This would mean the objects that could be effected by circular motion must be of an exalted substance. Circular motion is connected with more 'heavenly bodies' such as planets. The planets that were allowed to be in circular motion were spheres. These planets revolve around an Earth. He believed the initial motion of the objects was from a 'prime body' who acted on the outermost sphere. Since these spheres are moving in a circular motion, they could neither have weight or lightness as they cannot move naturally or unnaturally towards or away from the centre. The prime body was seen as always running and eternal, going past any other element. This element was known as aether or quintessence. Essentially, this was the fifth element which made up the Sun, planets and stars. Aether or αἰθήρ was described as a pure, perfect substance, which is unlike anything else on Earth.

Geocentric Model

The model created by Aristotle was a part of multiple examples described as the geocentric model. His model had a total of 55 objects in his idea of the universe. At the centre of the universe laid Earth. From the centre to the farthest exterior, the objects were as follows: Earth, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Past Saturn, stars were in a fixed position. The interesting part is if we change the position of the Earth and the Sun, then bring the moon to Earth, it would be pretty similar to our current model. This model and many like it lasted until the 16th century CE. Aristotle's universe gradually ended near the stars. The stars were the line between the universe seen by man. Past the stars laid spiritual space where mankind could never go.

Aristotle also created a theory on how the Earth was created and how the universe is laid out. He believed the Earth had always existed and was in an almost eternal state. The Earth, to his understanding, was unchanged and always provided a perfect circular motion for the revolving bodies. Aristotle argued for a spherical Earth. Around this time, the idea of a flat earth was coming into question. The proof provided by Aristotle was a moon's eclipse. When the moon eclipses, the boundary is always convex. So if the eclipses are due to the interposition of the earth, the shape must be caused by its circumference. Also, he mentioned that the stars provide evidence of Earth also being of no great size. His explanation was if an individual stood in Egypt, while another stood in Cyprus, they would see different sets of stars due to how small the Earth is. A vast change over a small amount of space. Since the Earth was in the centre and always existed, the next question Aristotle had was whether or not the Earth was unique.

Is Earth Unique?

Since the Earth is in the centre of the universe, and we live at the centre, does this mean the world is unique? Aristotle believed the Earth was unique and that mankind was alone in the universe. His hypothesis behind this was that if there were more than one world and the universe had more than one object at the centre, then elements like earth would have more than one natural place to fall to. The idea is that if multiple centres existed, the planets would be unable to revolve around Earth and have trouble understanding how to move. Remember, his idea of Earth, was that it was also the centre of motion. So by these standards, it makes sense for him to believe the Earth was unique.

The concepts put forth by Aristotle were incredible given the time. In roughly 350 BCE, he was able to identify rudimentary laws of motion prior to Newton's famous three laws. The ability to create a hypothesis of objects being heavier or lighter depending on the distance to the centre is also no small feat. His universe model consisted of 55 objects that aided in his observations and predictions regarding the motion of the planetary objects. The insight put forth by Aristotle was scientific theory at a rudimentary level, based on our model today, and his research shows the use of a scientific process. Though Aristotle's views were not all correct by today's current research, he did lay the fundamental framework for those like Galileo, Copernicus, and Newton. On the Heavens is just one of his many books that attempt to understand life, the universe, and everything. The examples used in this discussion are just the tip of the iceberg, and if anyone wants to read more on similar topics, please consider Physics and Meteorologica.