The metalworkers of ancient Korea were highly skilled artists and some of their finest surviving works are the large bronze bells cast for use in Buddhist temples and monasteries. Both the Unified Silla kingdom and Goryeo kingdom produced bells, but perhaps the most famous example is the 19-ton Emille Bell from Bongdeoksa which is considered one of the national treasures of Korea.

Origins & Function

Bronze bells were first made in Korea in the Bronze Age, but these were small items of uncertain use. They were not musical and may have been added to horse trappings or used in shamanist ceremonies, perhaps even carried as a symbol of authority. Musical bells were introduced from China in 1116 CE, and these were part of the aak orchestra which accompanied Confucian rites and ceremonies. The most famous bells of Korea, though, are those large cast bells (pomjong) used in Buddhist temples and monasteries. These too had been introduced from China during the Tang dynasty, but as with other arts such as papermaking and ceramics, the Koreans outdid their teachers and produced exceptionally large and finely decorated examples.

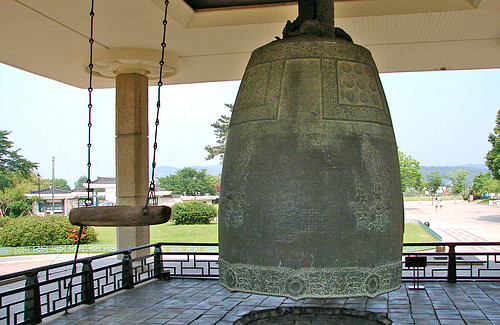

The large bronze bells of Korea did not have clappers as they were struck from the side using a horizontal wooden beam suspended by a rope. The bells themselves were suspended from the ceiling of a small purpose-built pavilion structure near the entrance to the temple. Large bells were rung to announce services at the beginning and end of each day while smaller bells heralded other services and rang out each hour.

Silla Bells

The largest and most famous bronze bells of Korea come from the Silla kingdom which had ruled south-east Korea from 57 BCE to 668 CE and then, as the Unified Silla Kingdom, the whole of the Korean peninsula until 935 CE. Metalwork had long been a fine Silla art, best seen in the gold crowns from various tombs and the gilded-bronze figurines and statues of Buddhist figures. The Unified Silla Period then saw a new art-form develop, that of making large bronze-cast bells which were hung in Buddhist temples.

Like Chinese bells, there are four square decorative panels (yugwak) near the top, each with nine knobs (ju) set in three rows of three. Silla bells differ, though, from Chinese bells of similar purpose in that they have pairs of flying apsaras carved in relief - the female heavenly beings who attend Buddha - and a much more elaborate design for the suspension of the bell, most often in the form of an intricately carved dragon and short hollow post which possibly acted as a sounding tube. The dragon and loop assembly on the crown (wu) of Korean bells is, therefore, a unique combination of Chinese hanging bells (chung) and handbells (t'o).

Added decoration typically includes bands of floral designs at the base and top of the bell (sangdae), most often using a motif of honeysuckle or the pao-hsiang-hua flower. In addition, the bells have a large lotus rosette near the base where the beam strikes the bell and one rosette on the opposite side.

The oldest surviving bell comes from the Sangwonsa temple on Mt. Odaesan near Pyeongchang and dates to 725 CE. The bell is 1.67 metres tall with a diameter of just under a metre and was funded by one Hyudori, the wife of a local aristocrat. The bell's decoration includes a flute and two harp players, and a lotus medallion surrounded by honeysuckle.

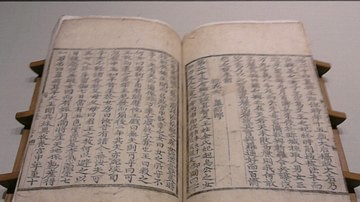

The largest Silla bell is from Bongdeoksa (Pandok-sa), also known as the Emille Bell, which was cast in 771 CE to honour King Seongdeok (r. 702-737 CE). An inscription on the bell informs us of the lengthy process needed to cast such giant bells. It states that the project was begun by Seongdeok's son King Gyeongdeok but he died in 765 CE when it was still not ready so that his son Hyegong was left to finish the job. According to a legend in the 13th-century CE Samguk yusa, the task was so overwhelming the man responsible for casting the bell that he was driven to throw his own daughter into the molten bronze in the hope that her sacrifice would allow the bell to be finally made. The sound of the bell when rung is thought to echo the girl's despairing cry of emille ('Mother') as she was thrown into the bronze, hence its popular name.

A close examination of the surface of the bell reveals that the mould was made of several different pieces and there were ten pouring holes in the crown. Around 3.5 metres tall and 2.27 metres in diameter, it is decorated with lotus flowers and heavenly beings with the classic Silla suspension loop in the form of a dragon. Weighing almost 19 tons, the bell is now on display in the Gyeongju National Museum. Even the Pandok-sa bell would have been dwarfed, though, by some of the larger bells which have, unfortunately, not survived. One, the Hwangnyong-sa bell, is recorded as having weighed a massive 500,000 kun or over 300 tons.

Goryeo Bells

The Goryeo dynasty ruled Korea from 918 CE to 1392 CE and Buddhism continued to be the most important religion of the state. 70 bells from this period survive with 17 of them carrying dates, the earliest being 963 CE. Many examples are today in Japan, given as gifts by the Yi government or looted during the 16th-century CE Hideyoshi invasion. Goryeo bells are smaller than the giant bells made by the Silla kingdom but can still be up to 1.7 metres tall. They, too, were cast in bronze and decorated with dragons and heavenly figures, but now also Buddhas and bodhisattvas too. If anything, the Goryeo bells are more decorative than their predecessors with one example from the Naesco temple in south-west Korea (1222 CE) having lotus leaf petals protruding from the upper rim of the bell, a more elaborate border around the nine-nodule squares, and four spheres added to the dragon suspension loop. Perhaps the most outstanding Goryeo example is the 1.7 metre tall bell now at the Toksu Palace Museum of Fine arts in Seoul.

Bells must not have been particularly popular with the local peasant populace as they were often compelled by monasteries and temples to 'donate' their bronze goods so that they could be melted down and recast into bells. This is probably the origin of the Bulgasari monster of Korean folklore. His name means 'Buddhist Temple Dweller' and he was thought to have lived off bronze and iron which he melted with his red-hot body. He was especially fond of needles and promised to chase away other monsters if his appetite was satisfied. Handbells and temple gongs were also produced in metal for use in Buddhist monasteries, and these smaller works were often beautifully inlaid with very fine pieces of silver or gold.