The Magical Lullaby (popularly known as Charm for the Protection of a Child) is an inscription from the 16th or 17th century BCE. The poem exemplifies the ancient Egyptian's personal religious and spiritual practices as it is a spell which was sung to ward ghosts away from sleeping children.

Magic (known as heka by the Egyptians after their god of the same name) was a common aspect of daily life and religious and medical practices in ancient Egypt. The Magical Lullaby is one example of the kind of spell which everyday people would use for protection. According to historian Margaret Bunson:

Three basic elements were always involved in the practice of heka: the spell, the ritual, and the magician. Spells were traditional but also changed with the times and contained words which were viewed as powerful weapons in the hands of the learned. (154)

Most people, however, were not 'magicians' and could not even read, and so certain spells were memorized by hearing and passed down generation to generation. The Magical Lullaby seems to be one such spell which could be sung by lay people for protection regularly without them having to consult with a priest, seer, or doctor.

MAGIC IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Magic was an integral part of the lives of ancient Egyptians. Magic, in fact, created and sustained the world. In the Coffin Texts (written c. 2134-2040 BCE) the god Heka states that he existed before the gods. He was the god of magic and the magic itself, the creative energy which enabled the creative act. Heka had always existed, would always exist, and informed every aspect of the Egyptians' lives. What one would consider 'supernatural forces' in the modern day were completely natural to them.

The gods and goddesses made regular and expected appearances daily, evil spirits and the angry dead needed to be guarded against, and even the most commonplace aspects of one's life, such as trees, brooks, rocks, and hills were imbued with a spiritual element. The rising and setting of the sun were events the ancient Egyptians believed they played a significant part in as they performed ceremonies to keep the serpent Apophis from destroying the boat of the sun god Ra and plunging the universe into chaos. Bunson notes how, "magic was the binding force between the earth and other worlds, the link between mortals and the divine" (154). Spells and rituals were used routinely for the most serious or mundane situations one encountered. Egyptologist James Henry Breasted comments on this, writing:

The belief in magic penetrated the whole substance of [ancient Egyptian] life, dominating popular custom and constantly appearing in the simplest acts of the daily household routine, as much a matter of course as sleep or the preparation of food. (200)

A priest, magician, physician, or seer who had acquired a certain amount of power and knowledge, was usually called upon in cases of illness, to interpret dreams, to mediate a dispute between the living and an angry spirit, or as mediator between human beings and the gods. Magic was evident in all the stories concerning the gods, and since human beings were considered co-workers with the deities, it made sense that the magical element was available to the people as it was to their gods. Egyptologist Rosalie David writes:

It was believed that society consisted of four groups - gods, the king, the blessed dead, and humanity - who shared certain moral obligations and a duty to interact in order to maintain world order. (271)

Part of the maintenance of the world, naturally, was one's health and well-being. Although the gods were always watching over one, it was clear their responsibilities were great and humans needed to do their own part to help protect themselves by regularly calling attention to themselves and their needs; and so magical charms, amulets, household statues, and incantations were regularly employed to drive away evil spirits or ghosts and keep the home safe. Egyptologist W.M. Flinders Petrie writes:

Children especially wore figures of Bes, and less commonly Taweret, the protecting genii of childhood...The household amulets in the prehistoric days were the great serpent stones with figures of the coiled serpent...in later times the image of Horus subduing the powers of evil seems to have been the protective figure of the house. (23)

Although Bes, Taweret, Horus, and many other deities offered protection, all of the gods and goddesses had their own special sphere of expertise. When one wished for help in love one called upon Hathor, for wisdom one would consult Neith, Thoth would assist one in writing, Ptah would dispense justice, and likewise, there was a god who specialized in protection through healing.

DOCTORS AS MAGICIANS

Heka was not only the god of magic but also of medicine. He is depicted as a man carrying a staff and knife and ancient Egyptian doctors were called Priests of Heka. Magic was as integral a part of medical practice in ancient Egypt as any other aspect of life, and so Heka became an important deity for doctors. He was said to have killed two serpents and entwined them on a staff as a symbol of his power; this symbol of the medical arts passed to the Greeks and on to the present day. One sees the symbol of Heka in modified form, now known as the caduceus, regularly in doctor's offices as the symbol of Hippocrates, father of medicine.

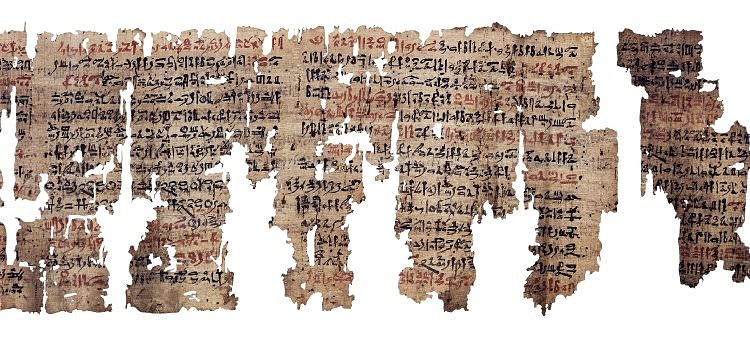

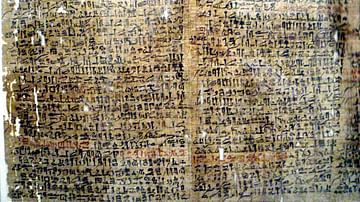

A papyrus dated to the reign of Amenhotep I (c. 1541-1520 BCE), now known as the Ebers Papyrus, is among the oldest medical texts in the world. It lists over 700 diagnoses and prescriptions with chapters on skin ailments, fractures, burns, digestive problems, as well as more serious conditions such as cancer and heart disease. This work demonstrates a high degree of medical knowledge and skill, and with another, the so-called London Medical Papyrus (c. 1629 BCE), also shows how magic and medicine were considered the same art. Another medical text, the Edwin Smith Papyrus (c. 1600 BCE), although offering primarily practical medical advice, also contains spells for healing.

Doctors could be expensive, however, or were simply unavailable and the gods, as noted, were very busy so the common people of Egypt became their own magicians and doctors when they had to. Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley writes:

The high levels of infant mortality meant that childhood illnesses were always worrying times for the mother. Very few parents could afford to take their sick children to consult doctors [and so] not surprisingly, mothers turned again to folk wisdom and magic to protect their darlings, placing their trust in a variety of charms, amulets, and spells. (79)

Illness in ancient Egypt, no matter one's age, was attributed either to the gods (who were punishing one for sins or teaching one a lesson), the dead (who were upset over some wrong done them in life or improper burial rites), or evil spirits who preyed on the unsuspecting and, especially, the innocent children. The Magical Lullaby is generally interpreted to address ghosts, rather than only evil spirits, as understood through the reference to them appearing in disguise (the lines, "who enterest in stealth, his nose behind him...who enterest in stealth, her nose behind her..."). This interpretation is challenged, however, and the lines are also interpreted to apply to evil spirits in general, not only disembodied ghosts of those who were once mortal.

THE TEXT

The poem is a short verse which speaks directly to the spirits who meant the child harm and warn of the weapons the speaker has for defense. The lines themselves, the spell, would be the 'weapon' in that it would scare the ghost away from the child but the variety of foods and spices mentioned were also potent defenses. Bunson comments on the work:

The Magical Lullaby is a charming song from ancient Egypt crooned by mothers over their children's beds. The lullaby was intended to warn evil spirits and ghosts from tarrying or planning harm. The mother sang about the items that she possessed in order to harm the spirits of the dead. She carried lettuce to 'prick' the ghosts, garlic to 'bring them harm', and honey which was considered 'poison to the dead.' (154)

The following translation comes from Development of Religion and Thought in Ancient Egypt by James Henry Breasted. The 'Efet-herb' mentioned is understood to be lettuce:

Run out, thou who comest in darkness, who enterest in stealth, his nose behind him, his face turned backward, who loses that for which he came.

Run out, thou who comest in darkness, who enterest in stealth, her nose behind her, her face turned backward, who loses that for which she came.

Comest thou to kiss this child? I will not let thee kiss him.

Comest thou to soothe him? I will not let thee soothe him.

Comest thou to harm him? I will not let thee harm him.

Comest thou to take him away? I will not let thee take him away from me.

I have made his protection against thee out of Efet-herb, it makes pain; out of onions, which harm thee; out of honey which is sweet to living men and bitter to those who are yonder (i.e. the dead); out of the evil parts of the Ebdu-fish out of the jaw of the meret; out of the backbone of the perch. (201)

COMMENTARY

The song is thought to have been sung fairly regularly by mothers, older sisters, and nurses throughout Egypt. Although it was obviously eventually written down, it may predate the 16th-17th century BCE and passed down through oral transmission, although this is speculation. Throughout the piece the speaker directly addresses the spirit who could be invisibly entering the home and, it was thought, drives it away.

According to scholar Andre Dollinger, the speaker would need to address both male and female spirits in the opening line because "magic spells are in some way akin to legal writings: they are effective only against those against whom they are specifically applied. Using only the male form in a curse would leave the child open to attacks from female demons" (1).

Dollinger further clarifies the lines, "Comest thou to kiss this child...Comest thou to soothe this child" as referring to ghosts which might appear friendly, even helpful, but are only really coming to harm the child. After making clear that the spirit will not get what he or she came for, the speaker threatens the ghost with the weapons at hand: lettuce, onions, honey, and the guts of fish.

The edibles mentioned suggest to some scholars (Breasted among the first) that the child may have been fed lettuce, onions, and honey with some fish as a preventative against possession. The reference to honey as sweet to the living but bitter to the dead is one of the lines scholars point to in interpreting the song as defense against ghosts, not evil spirits. Honey was considered bitter after death during some periods in Egyptian history. The line regarding the fish is interpreted in the same way. The Egyptians, especially of the lower classes, ate fish regularly but discarded the insides (the 'evil parts') as distasteful; the dead were thought to feel the same way.

Breasted's conclusion that the song actually relates a recipe which the child would eat makes sense, but it has also been suggested that these ingredients may have been mixed in a paste and applied to doorways and windows. Whether one actually made this mixture may not have mattered, however; perhaps just singing the song was enough to drive the ghosts away and keep one's child safe. Tyldesley writes:

These spells were known to be so effective that they were frequently written on a small scrap of papyrus packed into a specially carved wooden or gold bead and carefully suspended around the neck of the beloved child to ensure maximum protection. (80)

The popularity of such spells attests to the belief in their importance and the vital relationship the people had with the unseen world. The ancient Egyptians believed in a universe alive with supernatural possibilities. From tomb inscriptions to letters to stele to literature to the more obvious examples of charms and spells, it is clear that they saw the world imbued with spiritual forces of enormous power.

Although there were authority figures such as priests and seers who could advise them on how to navigate this world, they understood they also had to take personal responsibility for their lives, those of the larger community, and the maintenance of order and balance in the universe. The Magical Lullaby, sung by a caregiver to a child or tucked into an amulet one would wear, is an intimate glimpse into this grand vision of one of the greatest civilizations of the ancient world.