Ancient East Asia was dominated by the three states known today as China, Japan, and Korea. These kingdoms traded raw materials and high-quality manufactured goods, exchanged cultural ideas and practices, and fought each other in equal measure throughout the centuries. The complex chain of successive kingdoms in all three states has created a rich web of events that historians have sometimes found difficult to disentangle; a situation not helped by modern nationalist claims and ideals superimposed on antiquity from all three parties. As the historian Kim Won-Yong put it, "Korea acted as a cultural bridge between China and Japan" (Portal, 20). Historians continue to discuss whether that bridge was one-way or two-way traffic and, if the former, which direction, but suffice to say that there was such a bridge, and its consequences in art, politics, and history in both countries still resonate today.

First Trade Relations

It is likely that there was contact between the Japanese islands and the Korean peninsula in the Neolithic period (6,000-1,000 BCE), especially considering the lower sea-level at that time and so closer geographical proximity of the two land masses. However, the first recorded ties between Japan, specifically the island of Kyushu, which the Koreans called Wae (and the Chinese Wa), occurred in the period known as the Proto-Three Kingdoms period between the 1st and 3rd centuries CE. The fragmented territories in the south of the peninsula were not yet centralised states, but international relations were developed by the Chinese commanderies which occupied the north of Korea at this time, especially Lelang. Envoys and tribute were sent by the Wa, now a confederation of small states in southern and western Japan, the most important of which was Yamato. These missions are recorded in 57, 107, 238, and 248 CE.

Three Kingdoms Period

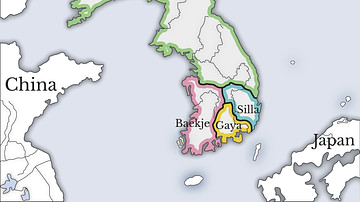

From the 4th century CE onwards Korea came to be dominated by the three kingdoms of Baekje (Paekche), Goguryeo (Koguryo) and Silla, with a fourth entity, less centralised, the Gaya (Kaya) confederation. Of these, relations were particularly close between Gaya and Japan. Scholars continue to debate which more influenced the other, and the issue is often coloured by nationalistic bias so that some historians claim that Gaya was a Japanese colony while others propose that horse-riders from the Eurasian steppe came to Japan via Gaya and introduced the burial tumulus to that culture. Evidence is lacking either way, although most scholars agree that the Gaya was the more advanced culture, and recent finds of iron horse armour, notably from the 5th-century CE tomb at Pokchon-dong, suggest that the Gaya did master the use of that animal.

From the Japanese side, the occupation of Korea in the 20th century CE sought historical justification from an interpretation of the Nihon shogi. Here in this text, dating to the 8th century CE, it is stated that between 369 and 562 CE parts of southern Korea were Japanese colonies. However, many historians discount the source as unreliable on such early history and, in any case, believe it to have been misinterpreted in order to suit nationalistic bias as Japan at this time did not have the technology, resources, or centralised government necessary to conquer foreign territories. Perhaps the complex relationship between the two states in this murky period of history is best summarised as follows by the historian M.J. Seth:

The Wa of western Japan may have lived on both sides of the Korean straits, and they appeared to have close links with the Kaya. It is even possible that the Wa and Kaya were the same ethnic group. The fact that the Japanese and Korean political evolution followed similar patterns is too striking to be coincidental. (32)

More certain than the precise political history is that iron was the most important Gaya export to Japan. Gaya potters likely passed on the innovation of high-fired grey stoneware (dojil) to Japan too, where the famous sueki (or sue) stoneware would be produced as a result. Gaya also exported manufactured iron goods such as agricultural tools, swords, riveted body armour, helmets, and arrowheads. Another successful export was the gayageum (kayagum), a zither with 12 silk strings thought to have been invented by King Gasil in the 6th century CE, which would be taken up by musicians in Japan and which remains a potent symbol of Korean culture even today.

The kingdom of Baekje also established trade and cultural ties with Japan during the Asuka Period (538-710 CE). Baekje culture was exported, especially via teachers, scholars, and artists, who also spread there elements of Chinese culture. Thus with traders and settlers from Baekje and Gaya came rice cultivation, wheel-thrown pottery, systems of social ranking, law codes and government, the classic texts of Confucius and the Altaic language of northeast Asia. Baekje monks may have spread Chinese writing to Japan in 405 CE and Buddhism in 538 CE. In addition, elements of Baekje architectural design can be seen in many surviving wooden buildings (e.g. the Horyuji temple in Nara) and in horizontal tomb chambers in Japan as a great number of Baekje craftsmen went there when Wa Japan was an ally.

That relations went beyond mere trade is evidenced by the joint Baekje-Gaya-Wa attack on Silla in 400 CE which was rebuffed by an army sent by the Goguryeo king Gwanggaeto the Great. In 660 CE, once again Baekje appealed (albeit unsuccessfully) for Wa military assistance in meeting a combined Silla and Tang dynasty army. Baekje was conquered, but rebel forces held out and managed to persuade their Japanese ally to send over a 30,000 man army. This was wiped out by a joint Silla-Tang naval force on the Baecheon (modern Kum) River, though, and Baekje's fate was sealed.

The Goguryeo kingdom likewise traded with ancient Japan and artists and scholars are known to have resided for a time at Yamato. Evidence of cultural exchange is most obviously seen in the tomb paintings for which the kingdom is celebrated today and the similar works in the c. 700 CE Fujinoki tomb in Ikaruga. It is probable that emigrants fleeing the collapsed Goguryeo kingdom following its demise at the hands of Silla took this and other cultural practices to Japan, just as their counterparts from Baekje did.

Unified Silla Kingdom

When the Unified Silla kingdom took control of the whole of the Korean peninsula from 668 CE relations were maintained with southern Japan, especially in the Nara and Heian periods. Trade relations and peaceful terms were in Japan's interest if they were to access the lucrative Chinese market unimpeded. Once again, though, open hostilities were never far away, as in 733 CE when Japan sent a fleet to attack Silla territory and again in 746 CE, this time with a 300-ship fleet. The following decades saw more regional stability and embassies were exchanged between the two governments. Trade was increased by the great Silla warlord Jang Bogo (d. 846 CE) and the kingdom even had a permanent administrative presence at Dazaifu in Kyushu, western Japan, where the Japanese employed a team of Silla translators. This was despite the fact that Silla pirates continued to harass Japanese coastal traders throughout the 9th century CE.

Goryeo Dynasty

When the Goryeo (Koryo) kingdom replaced Silla as the overlord of Korea from the early 10th century CE, trade relations continued and Japanese goods were imported, especially swords, mercury, tangerines, pearls, and paper folding fans. Goryeo exported in return grain, paper, ink, ginseng, straw mats, and books. Goryeo Buddhist monks travelled to Japan and left there evidence of their artistic and architectural skills. In 1231 CE the Mongols led by Ogedei Khan invaded Korea in the first of six attacks over the following decades. Finally, when peace was made in 1258 CE, the price for the Koreans was an obligation to provide ships and materials for the (failed) Mongol invasions of Japan in 1274 and 1281 CE.

Later History

Relations between Korea and Japan alternated between friendly trade partnerships and outright hostilities over the following centuries. Piracy became a major problem with large fleets transporting invading parties who pillaged deep into Korean territory. This led to King Taejong of the Joseon (Choson) kingdom attacking the Japanese pirate base on Tsushima Island in 1419 CE. Although this action did not eradicate the pirates (waegu) completely, it did allow for a trade deal to be agreed upon with Japan, the Treaty of Gyehae, drawn up in 1443 CE.

In the late 16th century CE many Korean potters and artists were forcibly taken to Japan following Toyotomi Hideyoshi's invasion of the Korean peninsula in a conflict sometimes referred to as the 'Pottery Wars' but more commonly as the Imjin Wars (1592-8 CE). These artists, already admired for the white porcelain they had been producing in great quantities, would have a significant influence on Japanese Satsuma ware. Korea was ravaged by the invasion, and many cultural sites and artworks were either destroyed or spirited away to Japan. Worse was to follow with the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-5 CE, fought on Korean soil, and full Japanese occupation of the peninsula until the end of World War II.

This content was made possible with generous support from the British Korean Society.