The pottery of ancient Korea stretches back to prehistory when simple brown wares were made and decorated with geometrical incisions and ends with the production of the superb celadons and white porcelain of the Goryeo dynasty but between these periods the Silla kingdom produced distinctive stoneware and pottery of its own. Whilst it is true that the majority of pottery from this period is strictly functional and was largely placed in tombs as mere containers for goods the deceased would require in the afterlife, there are also purely artistic creations, especially anthropomorphic spouted vessels which represent animals and people. These latter pieces employ a wide range of potter's techniques, and besides their aesthetic value, they have also provided historians with valuable insights into facets of daily life in ancient Silla from armour to architecture.

Korean ceramics produced after the Silla kingdom would become much sought-after in contemporary east Asia and subsequently the wider world, but it may be said that, splendid though these later pieces may be, they reflect a significant influence from Chinese ceramics. The pottery of the Silla period, in contrast, is markedly more 'Korean,' as the art historian Chewon Kim states,

Silla pottery may well be the most genuinely indigenous of all Korean art forms, in spite of the formal influences from outside which were brought to bear upon it. It varies from the near-primitive to the sophisticated, but it invariably has about it a natural quality which bespeaks its specifically Korean origin. (53)

Silla Kingdom (57 BCE - 668 CE)

Kilns

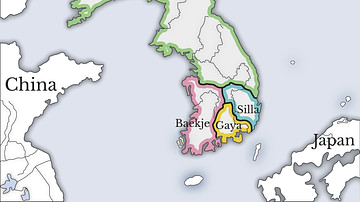

High-fired grey stoneware was produced by the Silla kingdom and the contemporary Baekje and Gaya states, too. Stoneware requires a high firing temperature (800°-1000° C), and this technology was, no doubt, connected to the furnaces required to produce iron in the Gaya confederation which was rich in that metal. Gaya potters likely received the technology from China via the northern commanderies such as Lelang and then passed on this innovation to their Korean neighbours and even Japan. The most common kiln type in Silla was the 'tunnel' or 'climbing' kiln, so-called because they were built into hillsides. They could be 20 metres long and 5 metres wide with shelving cut into the interior of the slope to stand pottery on and a chimney shaft dug to rise up the inside of the slope. There is no evidence of deliberate glazing in this period, although there are examples where accidental ash dropping from the kiln roof onto the pot did create a primitive glaze.

Forms

Typical Silla stoneware forms are the stemmed cup, short-necked bulbous jars, long-necked jars (changgyong ho) and kobae bowls with wide stands. Kobae were probably influenced by the Chinese dou and are typically between 25 and 35 cm tall. The lid with a small pedestal handle could be set upside down and serve as an extra dish. They were used on special occasions for food, not liquids. Examples of foodstuffs they contained when found in tombs include soybean paste, red pepper paste, kimchi (a seasoned vegetable dish), and fermented fish sauce. The long-necked jars were used to carry water, and their high neck reduced spillage. The base is either slightly rounded or indented, which aided their transport, traditionally on a small cushion placed on the carrier's head. Some jars have a foot attached, while those without would have been supported by a stand when not in use.

Other pottery shapes include horned cups, cups with wheels attached, one-handled cups, large bulbous jars with short necks (sometimes with pierced stands too), and bell cups which have small pieces of clay inside a hollow lower section so that they rattle when lifted. Miniature ceramic animal figures include rabbits, dogs, cows, pigs, tigers, tortoise, snakes, ducks, and one elephant (the latter is poorly rendered suggesting the potter had no model or personal experience to draw on). Most such figures come from the tombs at Hwangnamni, Gyeongju. Perhaps the most impressive pottery objects are the figurine ewers (tou) in the form of armoured horse riders, boats with a single oarsman, a two-wheeled chariot, and even temples and houses with thatched roofs. They were meant to pour rice wine or water during religious ceremonies and were placed in tombs to accompany the deceased into the next life.

Two of the finest examples of such figures were discovered in the Golden Bell Tomb at Gyeongju in 1924 CE. Both are horsemen (with the rider and horse being independent pieces), but one is a servant and the other is a warrior with details of costume and horse trappings rendered in applied clay pieces. The warrior or master figure is slightly larger at 25 cm tall and 29.5 cm long, no doubt also indicating his superior rank to his fellow. He wears an aristocratic peaked hat and short sword while his horse has a decorated saddle and bridle. The figures were so placed in the tomb that the servant was leading his master, as it were, into the next life. On both figures, the spout is on the chest of the horse and the funnel for filling the vessel is behind the rider. More rudimentary human figures have also been found in tombs. Male figures often have a simple cylindrical body, phallus, open or folded arms and appear to be singing suggesting they were fertility symbols.

Pottery stands (kurut pachim) were produced in the Baekje kingdom and the Gaya confederation, but they became something of a speciality in the Silla kingdom of the 5th and 6th century CE. Two varieties were manufactured: the first is a mere stand topped by a concave rim in which a bowl could be placed, while the second type has a bowl integrated into its top. Both types are more angular in profile than other Korean versions. Decoration takes the form of horizontal bands or cut-out rows of triangle and rectangle holes. Besides being used for serving food during meals, the large size of some of the stands suggests they might have been used in religious ceremonies.

Finally, ceramic lamps of the period most often take the form of a series of cups arranged around a larger central cup. Imitating metal lamps, the oil could pass through a channel connecting the base of each cup. Some examples have suspended leaf shapes as an extra decoration.

Decoration

Ceramics were decorated with incisions of geometric forms, especially circles, semi-circles, parallel and wavy lines, and V-shapes. Sometimes additional clay pieces, including three-dimensional figures, were added or portions of the clay were cut away to create a latticework effect. Added figures often reveal the daily life of the Silla kingdom and include copulating couples, musicians playing the zither (kayagum), and one with an A-frame (chige) to support carried goods on his back. Amongst other added three-dimensional decorations are leaves and snakes illustrating the importance of Shamanism in ancient Korea's religious practices. The suspended leaf decoration is reminiscent of Silla metalwork, especially gold crowns and earrings. Drawings of figures are rare, but there are some examples of simple human and animal forms incised onto vessels.

Unified Silla Kingdom (668-935 CE)

As the Three Kingdoms period gave way to the Unified Silla period where Silla gained control of the Korean peninsula, pottery began to display a marked influence from Buddhism. Cremation necessitated the manufacture of urns for ashes, and Buddhist motifs prevail as stamped decoration such as lotus buds for lid handles, lotus flowers, and clouds. Another Unified Silla use of ceramics was floor and roof tiles. The former have floral designs, especially honeysuckle and lotus flowers, while the latter can have fierce mask designs to ward off evil spirits. Roof tiles have been found in great numbers and are of two types: a semicircular form closed by a decorative disk at one end or a flatter version with a decorated edge. Both types were made using moulds, typically of clay and more rarely of wood.

As in the previous period, human and animal figures were produced, but these are now more sophisticated and attempt to capture details such as clothing – notably baggy trousers and long-sleeved tunics. Dancers, officials, soldiers, servants, and even bearded individuals were made which suggests contact with western Asians, probably via Tang dynasty China.

Everyday pottery was generally left undecorated, but special pieces, when they are decorated, show a greater density of designs than previously, now achieved by the use of stamps rather than by hand. There is, too, the first appearance of a deliberate ash glaze in the 8th century CE which, although rudimentary, would develop into the later celadon ceramics of the subsequent Goryeo period which would match the finest wares produced in China or anywhere else.

This content was made possible with generous support from the British Korean Society.