Contact between Korea and China goes back to mythology and prehistory. Trade developed from the Bronze and Iron Ages with raw materials and manufactured goods going in both directions for centuries thereafter. In addition to traders, migrants came, beginning with those escaping from the 4th-century BCE conflicts of the Warring States period, and a regular stream of diplomats, monks, and scholars travelled in both directions, too, so that Chinese culture spread to the whole of the Korean peninsula. Writing, religion, ceramics, coinage, agricultural practices, sculpture, and architecture were just some of the elements ancient Korea absorbed from its powerful neighbour, frequently adding their own unique cultural stamp and sometimes even outdoing their teachers.

The complex and sometimes subtle relationship between ancient China and Korea over the centuries is ably summarised by the historian M.J. Seth as follows:

China provided the model for literature, art, music, architecture, dress, and etiquette. From China Koreans imported most of their ideas about government and politics. They accepted the Chinese worldview in which China was the centre of the universe and home of all civilization, and its emperor the mediator between heaven and earth. Koreans took pride in the adherence to Chinese cultural norms...they accepted their country's role as a subordinate member of the international hierarchy in which China stood at the apex, loyal adherents of Chinese culture such as Korea ranked next, and the barbarians outside Chinese civilization stood at the bottom. Close adherence to civilized standards was a source of pride. But this did not result in a loss of separate identity...Nor did Korea's membership in the “tributary system” in which the Korean king became a vassal of the Chinese emperor mean that Korea was less than fully independent...In fact, Koreans were fiercely independent...Korea's position as a tributary state was usually ceremonial, and for Koreans it did not imply a loss of autonomy. Chinese attempts to interfere in domestic affairs were met with opposition. (4-5)

To better understand this three-stranded relationship of politics, commerce, and culture, it is necessary to examine each of the historical periods of ancient Korea in turn as political developments in the peninsula and China would both strengthen and strain the relationship in equal measure over more than a millennium of international relations.

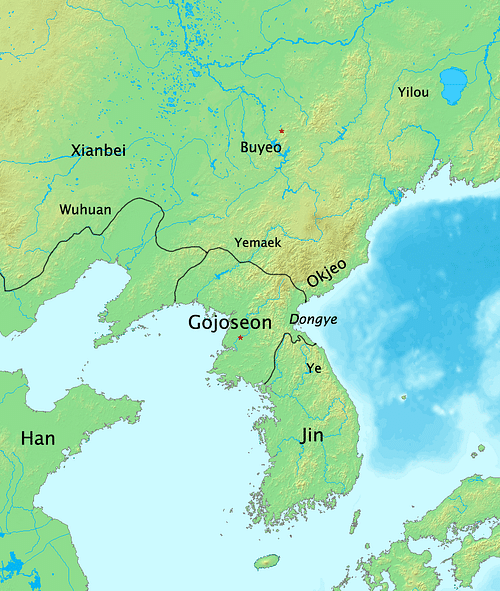

First Relations - Gojoseon

Archaeology has revealed that the Korean peninsula received material culture – notably metalworking skills and rice cultivation – from migrating tribes from Manchuria, Siberia, and China in the Neolithic period. Korean mythology describes the earliest contact with China as when the sage Gija (Jizi to the Chinese) and 5,000 followers left China and settled in Dangun's kingdom of Gojoseon, Korea's first state. When Dangun decided to retreat to a life of meditation on a mountaintop, Gija was made king in 1122 BCE. The myth may represent the arrival of Iron Age culture to Korea. The historical rulers of Gojoseon did adopt the Chinese title wang (king) illustrating an early influence from neighbouring Yan China, probably a trade partner, perhaps with Gojoseon acting as middleman between China and the southern states of Korea. Another indicator of trade relations is the discovery of Chinese crescent knife coins (mingdaoqian) at various Korean sites.

Archaeological evidence of Chinese cultural influence is perhaps best seen in the use of pit burial tombs in the Daedong River area and the frequent presence of horse trappings and luxury goods therein. The tombs are also of interest as several contain over 100 slaves buried with and presumably belonging to the occupant. With better iron tools introduced from China, agricultural production increased and so the general prosperity of Gojoseon.

Chinese culture was brought directly to Korea by refugees fleeing the 4th-century BCE conflicts of the Warring States period. The Chinese Han dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE) established four military colonies, referred to as commanderies, in Manchuria and northern Korea. These prospered on trade and brought Korea into the wider political sphere of Han-dominated East Asia. Lasting until the 4th century CE, the most important in terms of population and resources was Lelang (aka Nangnang, 108 BCE - 313 CE). Their presence greatly increased material contact between China and Korea, populated as they were by expatriate Chinese (huachiao or huaqiao) supplied with all the goods they were used to enjoying back home.

Three Kingdoms Period

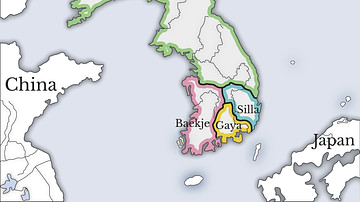

The Three Kingdoms period (1st century BCE to 7th century CE) sees the beginning of recorded history in ancient Korea. These centuries saw the kingdoms of Baekje (Paekche), Goguryeo (Koguryo), and Silla, and the Gaya (Kaya) confederation, in a continuously shifting political landscape of mutual alliances and conflict between each other and China with the aim of territorial expansion. Despite these conflicts, trade and cultural exchange between the peninsula and China continued and increased. The Three kingdoms period, then, was a time when the Korean states were able to take advantage of the four centuries of political fragmentation that China suffered between the fall of the Han in the early 3rd century CE and the rise of the Sui dynasty from 581 CE and push forwards to achieve their own cultural development by absorbing and adapting the best cultural and political practices of ancient China.

Baekje & Gaya

Early relations between the Gaya confederation and Han China is evidenced by 1st-century CE Chinese coin finds at Bon-Gaya and by the presence of the sloping kiln used by Gaya potters. Iron, gold, and horses went to China, and silk, tea, and writing materials came in the other direction. There were close cultural ties too, with the Koreans adopting the Chinese writing system and the Chinese kingly title of wang being adopted by Baekje monarchs from the 3rd century CE. Literature, burial practices, and elements of art were passed on, too.

The Korean states, traditionally practitioners of shamanism, adopted first Confucianism, then Taoism and Buddhism from China making the latter the official state religion. The Baekje kingdom officially adopted Buddhism (which had originated in India but acquired distinctly Chinese elements) in 384 CE after its introduction there by the Indian/Serindian monk Marananta. Confucianism would greatly influence Korean society, politics, ethical thought, and family relationships, while Buddhism, besides becoming the most widely practised religion, would have a tremendous impact on art, architecture, literature and ceramics.

Goguryeo

The northern Goguryeo kingdom was a frequent trading partner of China's, with the former exporting gold, silver, pearls, and textiles while China sent weapons, silk, writing materials in return. There were also close cultural ties between the two, with Goguryeo adopting the Chinese writing system, wuzhu coins (known locally as oshuchon), Chinese poetry style, architectural elements (especially regarding tombs), art motifs (again seen in tombs such as constellations painted on ceilings and images of the Chinese animals of the four directions), and belief systems. In 372 CE a National Confucian Academy was created and Buddhism was adopted as the official state religion (replacing the predominant Shamanism) when it was introduced by the monk Shundao (Sundo to the Koreans).

Goguryeo, situated as it was in the north, bore the brunt of the political ambitions of China's new dynasty, the Sui (581-618 CE). A Chinese combined navy and army of 300,000 attacked in 598 CE, actually in response to a Goguryeo pre-emptive strike, but was defeated largely by weather conditions. Another attempt was made in 612 CE but was again unsuccessful following the Battle of Salsu River where the Koreans were ably led by the famous general Eulji Mundeok. According to legend, of the 300,000-strong Sui army only 2,700 returned to China. The capital Pyongyang withstood a lengthy siege and Goguryeo stood firm. Two more attacks we rebuffed in 613 and 614 CE and Goguryeo built a 480 km (300 miles) long defensive wall in 628 CE so as to deter any further Chinese ambitions. The defeats would contribute to the fall of the Sui dynasty, but their successors, the Tangs, proved just as ambitious for territorial expansion and rather more effective in achieving it.

Silla

In the 4th century CE, the Silla kingdom maintained diplomatic relations with China, paying regular tribute to the regional powerhouse. From the 6th century CE, Silla rulers also adopted the Chinese wang title, the Chinese writing system, Confucianism, and Buddhism. The latter became the official state religion in 535 CE, even if traditional shamanistic practices continued too, as in the other states. When Taoism became more popular during the Tang period (618-907 CE), so too it became more widespread in the Silla kingdom.

The two states were long-time trading partners with China exporting silk, tea, books, and silver goods while Silla sent in return gold, horses, ginseng, hides, ornamental manufactured goods such as tables and slaves. The reigns of Queen Seondeok and king Taejong Muyeol in the mid-7th century CE saw an even closer relationship with Tang China with Tang court customs followed at Kumsong, students sent to China for study, and most significantly of all, massive military aid being sent to help Silla quash their rival kingdoms. Emperor Gaozong sent a navy of 130,000 men in the hope that Silla would defeat the other states and then could itself be destroyed. The Koreans, though, had other plans. While the Tangs were preoccupied with a rising Tibet, the Silla armies battled the Chinese forces remaining in Korea. Battles at Maesosong (675 CE) and Kibolpo (676 CE) brought victory and finally, Silla was the sole master of Korea.

Unified Silla Kingdom & Balhae

Despite the Silla kingdom's refusal to become just another Chinese province, relations with China were not soured, in fact, the young Korean state became a loyal ally. The influence of Chinese culture continued to be significant and both Confucianism and Buddhism remained an important part of the Silla education system. Buddhism was still the official state religion, practised by all levels of society. The most famous of all Buddhist scholar-monks belongs to this period – Wonyho, who popularised the faith in the 7th century CE. If anything, Confucianism became stronger in the Unified Silla with a National Confucian Academy established in 682 CE and an examination for state administrators introduced in 788 CE.

There was a healthy trade between the two states too with Chinese luxury goods such as silk, books, tea, and art being imported while Korea exported metals (especially gold and silver), ginseng, hemp goods, manufactured goods, horses, and sent students and scholars to China. There were even Silla controlled trading areas in Chinese territory, such was the volume of trade.

Contemporary with the Unified Silla Kingdom, but occupying territory in the north of the Korean peninsula and Manchuria, was the state of Balhae (aka Parhae, 698-926 CE). Balhae, although at times trading with its neighbours, unwisely attacked both Silla and Tang China in the first half of the 8th century CE, which compelled the two to once more form an alliance to quash a common enemy. This time, however, the northern mountains proved too hostile an environment and the joint Silla-Tang expedition failed spectacularly with Silla losing half of its army amongst the snowy peaks. The Balhae kingdom continued to prosper thanks to its close relations with Japan, but in the early 10th century CE the end swiftly came when it was attacked and conquered by the Mongolian Khitan tribes. Its territories and those of the declining Silla kingdom would be taken over by Korea's new rising power, the Goryeo dynasty.

Goryeo Dynasty

The Goryeo (Koryo) dynasty, after another round of inter-state fighting known as the Later Three Kingdoms period (889-935 CE), conquered the whole of the Korean peninsula. As in previous times, a respect for Chinese culture and ability to practise its ideals continued to be a mark of gentility amongst the Korean elite. As Goryeo's founder Taejo declared, "We in the East have long admired Tang ways. In culture, ritual, and music, we are entirely following its model" (Portal, 79).

Goryeo subsequently established even stronger ties with China's Song dynasty (960-1279 CE). The Song took advantage of these friendly relations and requested that Goryeo help them deal with the Khitan and Jin, but the Koreans were not keen to be embroiled in a wider regional conflict. Tribute was paid to China, but both state-sponsored and private trade included all manner of goods moving in both directions. China exported silk, books, spices, tea, medicine, and ceramics while Goryeo sent gold, silver, copper, ginseng, porcelain, pine nuts, and hanji paper. Such were the number of goods available that in the 13th century CE Songdo, the Goryeo capital, boasted over 1,000 shops.

Cultural ties were also strong with Chinese literature being very popular, and the state administration modelled on the Chinese approach with a civil service examination introduced in 958 CE and Confucian principles followed. Buddhism remained the state religion with many more temples and monasteries being built. In this period Korea began to mint its own coinage which imitated those of the earlier Tang dynasty. Even the 'heavy coin of the Qianyuan period' inscription was translated from the Chinese (Qianyuan zhongbao) to the Korean Konwonchungbo. The Goryeo mint did add an identifying mark such as 'Eastern kingdom' (Tongkuk) on the reverse side of their coins but, as with Chinese coins, the Korea coins had a square central hole.

Later History

A new threat to Korea emerged in the early 13th century CE when the Mongol tribes, united by Genghis Khan (Chinggis), swept through China and conquered Beijing in 1215 CE. Then in 1231 CE, the Mongols, now led by Ogedei Khan, turned their attention to Korea, forcing Goryeo to move its capital. There would be six more Mongol invasions over the next three decades, but by 1258 CE peace was made. The price was an obligation for Goryeo to provide ships and materials for the (failed) Mongol invasions of Japan in 1274 and 1281 CE. Korea then became increasingly influenced by Mongol culture, princes were required to live as hostages in Beijing and several kings married Mongolian princesses. Korea would have to wait another century to re-establish its independence when, in 1392 CE, the new state of Joseon was formed.

This content was made possible with generous support from the British Korean Society.