Dolmens (in Korean: koindol or chisongmyo) are simple structures made of monolithic stones erected during the late Neolithic period or Korean Bronze Age (1st millennium BCE). In ancient Korea they appear most often near villages and the archaeological finds buried within them imply that they were constructed as tombs for elite members of the community. Over 200,000 megalithic structures have been recorded in Korea with 90% of them in South Korea where they have the status of protected monuments. Most of the stones used are massive with the largest example found being 5.5 metres wide and 7.1 metres tall, and many weigh over 70 tons.

Geographical Spread

Archaeological evidence illustrates that Bronze Age culture spread down into the Korean peninsula from Manchuria, especially the Sungari and Liao River basins. Mixing with the indigenous Neolithic population, this new culture likely created a societal elite which was responsible for and was honoured by the erection of dolmen tombs. The presence on the Korean islands of Jeju and Ganghwa and areas of Japan of similar dolmens suggests that the cultural wave did not stop at the Korean mainland but also crossed the relatively narrow straits to the Japanese islands.

Design

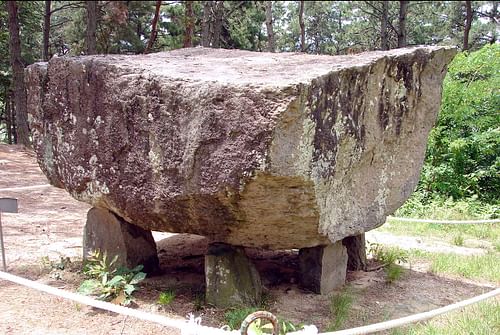

The dolmen structures can take three different forms and precise configurations differ depending on the region. The first type, more common in the north of the peninsula (across the Han River), is the 'table' or takcha form where one large stone rests horizontally on two or more upright stones often arranged in a square. The second type, known as paduk, has one large flat stone set on top of a mound of smaller stones. The third type, seen more often in the south, has a single large stone laid flat above a small rectangular buried tomb which is lined with stone slabs and usually measuring 2000 x 30 cm. Alternatively, the tomb may consist of a simpler jar burial, perhaps for a child. The first type of dolmen most often occurs in isolation while the others are sometimes found set in rows or groups.

An explanation for the design of dolmens is suggested by the historian Jinwung Kim as follows:

The appearance of dolmen tombs is unique. The round, flat capstone presumably symbolised heaven and the square upright stones represented the earth; people at the time believed that the souls of their chieftains reposed where heaven and earth met. (8)

Outstanding examples of ancient Korean dolmens are the table-type structures on Ganghwa Island which date to c. 1000 BCE in the Korean Bronze Age. Single standing stones (menhirs), unrelated to a burial context and perhaps used as marker stones, are also found across Korea.

Excavation

While dolmens usually occur as a single isolated monument, there are 'cemeteries' in the south which consist of 30-100 examples placed in close proximity, sometimes in a straight line. This would suggest that the individuals interred therein were part of the same elite class, perhaps too, the same dynasty of rulers. Dolmen tombs typically contain the remains of a single individual whose status is revealed by the precious bronze goods within and by the very fact they had a tomb constructed which involved the intense labour of moving the dolmen stones over many kilometres from their source. The enormous size of the stones involved would also suggest that the communities that built them were more than just villages, such was the manpower needed in moving the stones.

Excavations of the tombs under dolmens have revealed bronze goods such as daggers, swords, bells, and mirrors, but also polished stone daggers and burnished pottery. Several tombs also contained jade or amazonite beads, some in the crescent shape known as a gogok which possibly originated in Siberia and represents new life. Gogok (aka kogok) would reappear in later ornamentation, notably on the golden crowns of the Silla kingdom (57 BCE - 935 CE). One of the richest tombs is at Namsong-ri, containing more than 100 bronze artefacts which besides mirrors and daggers include an axe, chisel, a lacquered birch-bark scabbard, and tubular-shaped jade beads. It may be that some objects were those of a shaman, and there is evidence that shamans were also tribal chiefs in early Korea.

Unanswered Questions

One curiosity which historians and archaeologists have yet to solve is why the finds in tombs vary and those with more precious bronze goods are actually the least impressive dolmens. The significance of the size of the capstone has also been debated amongst scholars and whether that signifies the status of the buried individual within. Exactly how the stones were erected is an additional source of disagreement, and another issue is the great similarity between Korean and European dolmens (e.g. at Carnac and Locmariaquer in France) without any evidence of contact between the two areas at the time of construction. It is clear that these impressive but mysterious monuments will continue to pose puzzling questions, just as they, no doubt, have to the successive ancient cultures of Korea who left them intact for posterity.

This content was made possible with generous support from the British Korean Society.