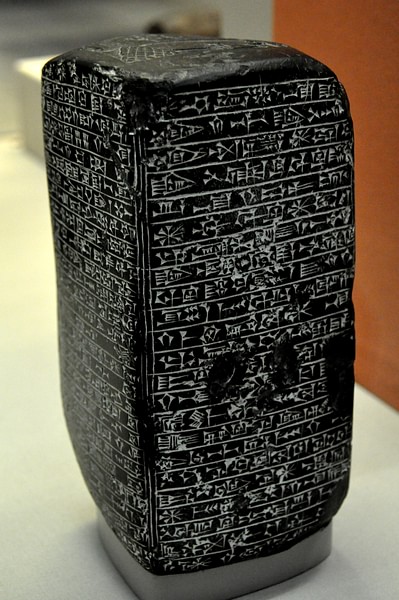

The Marduk Prophecy is an Assyrian document dating to between 713-612 BCE found in a building known as The House of the Exorcist adjacent to a temple in the city of Ashur. It relates the travels of the statue of the Babylonian god Marduk from his home city to the lands of the Hittites, Assyrians, and Elamites and prophesies its return at the hands of a strong Babylonian king. The original work was almost certainly written during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar I (1125-1104 BCE) as a propaganda piece. Nebuchadnezzar I defeated the Elamites and brought the statue back to Babylon, and the work was most likely commissioned to celebrate his victory.

The author would have constructed the narrative to place the events in the past in order to allow for a 'prophetic vision' in which the present king would come to restore peace and order to the city by bringing home the statue of the god. This form of narrative was commonplace in the genre now known as Mesopotamian Naru Literature where historical events or individuals were treated with poetic license in order to make a point. In a work such as The Curse of Akkad, for example, the historical king Naram-Sin (2261-2224 BCE), known for his piety, is presented as impious in an effort to illustrate the proper relationship between a monarch and the gods. The point made would be that if a king as great as Naram-Sin of Akkad could fail in piety and be punished, how much more would a person of lesser stature fare. In The Marduk Prophecy, the events are placed far in the past in order for the writer to be able to 'predict' the moment when a Babylonian king would return Marduk to his rightful home. This piece, then, also deals with the responsibility a monarch has to his god.

In reading the text, one easily recognizes the mythical qualities and political themes - such as Marduk's statue expressing satisfaction with the lands of the Hatti and Assyrians - both considered allies or even closer - but distaste for the land of Elam - a traditional enemy of Babylon - but is also aware the work is drawing on actual historical events. The removal of a god's statue from a conquered city was common practice and was considered a devastating loss to the conquered. This was true of any god in any city but more so with Marduk and Babylon owing to their respective lofty reputations.

Marduk King of the Gods

In Mesopotamian mythology, Marduk was the son of Enki (also known as Ea), the god of wisdom, who became elevated to the position of king during a great battle between the forces of the older gods and those of their children. According to the Enuma Elish, the universe was originally a watery chaos until it divided into sweet water (known as Apsu, the male principle) and salt water (known as Tiamat, the female principle). Apsu and Tiamat then gave birth to the other gods who, with little to do, occupied themselves as best as they could.

In time, the antics of his children began to annoy Apsu who decided, on the advice of his vizier, to kill them. Tiamat, hearing of this, revealed the plot to Enki, who then moved first, put his father into a deep sleep, and killed him. Tiamat was horrified at this and raised an army to destroy her children. Led by her consort Quingu, the forces of Tiamat were victorious in every engagement. The younger gods were beaten back until Marduk stepped forth at a council meeting and announced he would lead them to victory if they would make him their king. Once they agreed, he defeated Quingu (who would later be executed) and killed Tiamat with a great arrow which split her in two.

Having defeated the forces of chaos, Marduk set about the creation of the world, the ordering of the heavens, and the formation of a new creature called a human being. Humans would be co-workers with the gods to hold back the forces of chaos and maintain order in the world. In this way, all humans were children of Marduk who worked to do his will. Marduk's story became so popular that he became recognized as the supreme god. Scholar Jeremy Black notes that "the worship of Marduk in its most extreme form has been compared with monotheism though it never led to a denial of the existence of other gods" (129). Marduk, then, was extremely important to the people of Mesopotamia but especially to those of the city of Babylon.

Marduk's Importance to Babylon

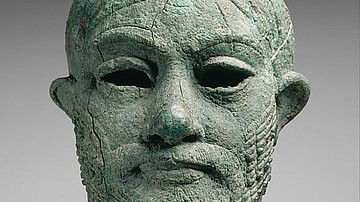

Marduk rose to prominence as the patron deity of Babylon during the reign of Hammurabi (1792-1750 BCE) and continued to be venerated in the city up through the time of Persian rule until Babylon was destroyed in c. 485 BCE by Xerxes the Great. The New Year's festival (known as the Akitu Festival) could not be celebrated when the god's statue was absent from the city as this was thought to symbolize the departure of the actual god's presence. Marduk was thought to live in his temple in the center of the city just as the gods of other cities lived in theirs. When a god's statue was removed, the protection that deity afforded was lost as well. The Marduk Prophecy relates the kinds of conditions which followed when a god left or was taken from a city:

People's corpses block the gates. Brother eats brother. Friend strikes friend with a mace. Free citizens stretch out their hands to the poor to beg. The sceptre grows short. Evil lies across the land. Usurpers weaken the country. Lions block the road. Dogs go mad and bite people. Whoever they bite does not live, he dies. (Van de Mieroop, 48)

Scholar Marc van de Mieroop comments on this situation, writing:

The absence of the patron deity from his or her city caused great disruption in the cult [of that deity and city in general]. The absence of the divinity was not always metaphorical but often the result of the theft of the cult statue by raiding enemies. Divine statues were commonly carried off in wars by the victors in order to weaken the power of the defeated cities. The consequences were so dire that the loss of the statue merited recording in the historiographic texts. When Marduk's statue was not present in Babylon, the New Year's festival, crucial to the entire cultic year, could not be celebrated. (48)

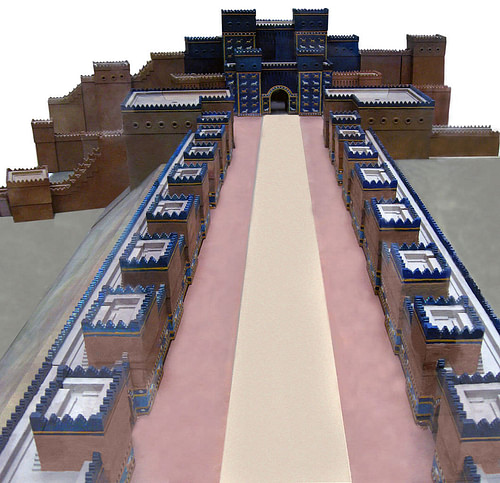

Babylon was sacked by the Assyrian ruler Sennacherib (705-681 BCE) in 689 BCE after Sennacherib had earlier snubbed Marduk as god of the city as well as the ritual of 'taking the hand' of the god when he proclaimed himself king of Babylon. When he was assassinated by his sons in 681 BCE, it was considered Marduk's retribution for the insult to himself and his city. Sennacherib's successor Esarhaddon (681-669 BCE) went to great pains to distance himself from his father in rebuilding the city and honoring Marduk with an even grander temple, the great ziggurat of Babylon (model for the biblical Tower of Babel) where, according to Herodotus, the people believed the god himself came down from the heavens to mate with specially chosen virgins who lived at the top level.

Herodotus' claims aside, however, Marduk was understood to reside in his temple, not the heavens, among the people of his city. At the New Year's festival, his statue was paraded through the streets and out to a small house beyond the walls where he could enjoy a different view and some fresh air. Marduk was not a far off deity on some higher plane but instantly accessible and always available to the people. It was especially difficult for the Babylonians, therefore, when their protector and friend was taken from them.

Marduk's Travels

The Marduk Prophecy gives no clear timetable of events, but it is now known, from other sources, when certain invasions took place and when the statue of the god was carried off. Further, the work does not follow the fate of the statue after it is returned to Babylon from Elam. A timetable of the travels of Marduk would run from the first time the statue was taken by the Hittites until its final destruction by the Persians under Xerxes, and this later history is supplied by Greek writers. The journey of the statue of Marduk would follow along these approximate dates:

c. 1595 BCE - Mursilli I of the Hittites carries the statue off to the Land of the Hatti after sacking Babylon.

c. 1344 BCE - Hittite King Suppiluliuma I possibly returns the statue to Babylon as a gesture of goodwill in trade (this is speculative).

1225 BCE - Tukulti Ninurta I of Assyria sacks Babylon and carries statue back to Ashur.

Although there have been some suggestions that the city of Ashur was sacked after Tukulti Ninurta I's death in 1208 BCE, this does not seem probable. The next time the statue is mentioned it is in the possession of Shutruk Nakhunte of Elam who most likely took it from the city of Sippar where it had been moved at some point.

c. 1150 BCE - Shutruk Nakhunte, King of Elam, acquires the statue in his sack of Sippar. Shutruk Nakhunte's inscription boasts of him destroying Sippar, a city near to Babylon, and carrying off many goods of religious and cultural value - including the stele of the great Naram-Sin - so it is probable that the statue had made its way to Sippar.

1125-1104 BCE - Reign of Nebuchadnezzar I who defeats the Elamites and brings the statue back to Babylon.

705-689 BCE - The statue remains in Babylon during Sennacherib of Assyria's reign until he sacks the city in 689 BCE and removes the statue, most likely to Nineveh.

681-669 BCE - Esarhaddon, Sennacherib's son, rebuilds Babylon, returns the statue, and honors Marduk with a new temple.

668-627 BCE - Reign of Esarhaddon's son Ashurbanipal during which the statue remains in Babylon.

c. 634 - c. 562 BCE - Reign of Nebuchadnezzar II during which the streets were widened so that the statue of Marduk could be more easily paraded on festival days and especially at the New Year when it would be carried out through the Ishtar Gate to the special house.

c. 539 - Babylon is conquered by Cyrus the Great of Persia. Cyrus had great respect for the city and its god. An inscription on a clay barrel in Cyrus' tomb justifies his assault on Babylon and relates how Marduk was on his side and is due praise for his victory. The conquest of Babylon is justified in that Cyrus claims the king had forgotten due praise to Marduk and was unfit to rule.

c. 485 BCE - Babylon revolts against Persian rule and Xerxes I the Great destroys the city in retaliation, melting down the gold statue of Marduk.

The Reliability of the Sources

As noted, The Marduk Prophecy is historical fiction created to celebrate the victory over the Elamites of Nebuchadnezzar I. The sources which trace the fate of the statue following its return to Babylon are historical in nature, but the two central writers - Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus - have both been criticized for inaccuracies and outright fables in their respective works. Herodotus' accounts of Babylon have seemed suspect to readers since his own age, and Diodorus is responsible for the elaborate description of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, which scholars now believe, if they existed at all, were at Nineveh. Both of these writers were vehemently anti-Persian, and a story of a Persian king destroying the statue of a god to teach a lesson to the people of a city he had just razed would have neatly furthered their respective agendas in portraying the Persians as insensitive, brutal, and impious.

The final fate of the statue of Marduk, then, according to the Greek writers, might well be suspect but for the fact that there is no more mention of the statue in any sources after Xerxes' assault on Babylon and no ancient writers contradict Herodotus' account. Babylon was taken by Alexander the Great when he conquered the Persian Empire in 331 BCE, and no mention is made of the statue nor is it ever mentioned in later accounts. It would seem, then, that Herodotus and Diodorus are correct in their conclusions unless some as-yet undiscovered source appears to present a different story.

The Marduk Prophecy is not so much relevant as history as it is in understanding the great value the people of a city placed on their patron deity. Marduk was not just some invisible, ethereal being one prayed to in time of need or praised in time of plenty, but a close friend and neighbor who lived just down the road. In the same way one would be distressed today to find one had lost a close friend, so was it to the ancient Babylonians when the statue of their god was taken from them.