The Plague of Cyprian erupted in Ethiopia around Easter of 250 CE. It reached Rome in the following year eventually spreading to Greece and further east to Syria. The plague lasted nearly 20 years and, at its height, reportedly killed as many as 5,000 people per day in Rome. Contributing to the rapid spread of sickness and death was the constant warfare confronting the empire due to a series of attacks on the frontiers: Germanic tribes invading Gaul and Parthians attacking Mesopotamia. Periods of drought, floods and famine exhausted the populations while the emperorship was rocked with turmoil. St. Cyprian (200-258 CE), bishop of Carthage, remarked that it appeared as if the world was at an end.

Naming & Interpretation

The outbreak was named after Cyprian as his first-hand observations of the illness largely form the basis for what the world would come to know about the crisis. He wrote about the incident in stark detail in his work De Mortalitate (“On Mortality”). Sufferers experienced bouts of diarrhoea, continuous vomiting, fever, deafness, blindness, paralysis of their legs and feet, swollen throats and blood filled their eyes (conjunctival bleeding) while staining their mouths. More often than not, death resulted. The source of the terrible affliction was interpreted by pagans as a punishment from the gods. This was not an unusual interpretation from a pre-Christian or early Christian culture throughout the Mediterranean world which understood disease to be supernatural in origin. Later scholars and historians sought alternative explanations.

Nature of the Disease

Identifying diseases from the ancient world is always difficult as the state of medicine and diagnosis lacked the degree of knowledge and sophistication available to modern science. Based upon the surviving accounts, the illness appeared to be highly contagious, transmitted both by direct and indirect contact (including through clothing). Throughout the centuries since the episode, scholars suggested a number of possibilities for the disease which ravaged the empire in the 3rd century CE: bubonic plague, typhus, cholera, smallpox, measles and anthrax. The lack of certain tell-tale symptoms eliminated many of these early suspects e.g. bubonic plague was eliminated as the contemporaneous accounts make no mention of swellings or buboes on the bodies of the afflicted. The variety of known symptoms suggested a combination of diseases including meningitis and acute bacillary dysentery. Kyle Harper, in his article “Pandemics and Passages to Late Antiquity,” argued that the most likely culprit was a viral hemorrhagic fever possibly Ebola.

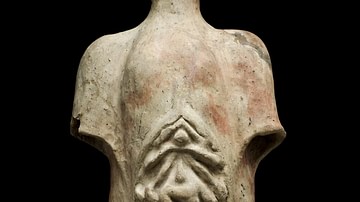

A potential breakthrough in identifying the disease occurred in 2014 CE when Italian archaeologists unearthed bodies from the Funerary Complex of Harwa at Luxor (formerly Thebes). It was discovered that attempts were made to stop the spread of the disease by covering the corpses with lime as well as burning the bodies. Attempts to extract DNA from the remains proved futile as the Egyptian climate causes the complete destruction of DNA. Without the DNA evidence, there may never be conclusive proof as to the actual disease(s) that ravaged Rome and the empire 1,800 years ago.

Consequences

The disease episode of the mid-200s CE caused political, military, economic and religious upheaval. In addition to the thousands of people dying per day in Rome and the immediate vicinity, the outbreak claimed the lives of two emperors: Hostilian in 251 CE and Claudius II Gothicus in 270 CE. The period in between the emperors witnessed political instability as rivals struggled to claim and hold the throne. The lack of leadership and the depletion of soldiers from the ranks of the Roman legions contributed to the deteriorating condition of the empire by weakening Rome's ability to fend off external attacks. The widespread onset of illness also caused populations in the countryside to flee to the cities. The abandonment of the fields along with the deaths of farmers who remained caused the collapse of agriculture production. In some areas, swamps re-emerged rendering those fields useless.

Only the nascent Christian church benefitted from the chaos. The illness claimed the lives of emperors and pagans who could offer no explanation for the cause of the plague or suggestions for how to prevent further illness much less actions for curing the sick and dying. Christians played an active role in caring for the ill as well as actively providing care in the burial of the dead. Those Christians who themselves perished from the illness claimed martyrdom while offering non-believers who would convert the possibility of rewards in the Christian afterlife. Ultimately this episode not only strengthened but helped to spread Christianity throughout the furthest reaches of the empire and Mediterranean world.