Baal (also given as Ba'al) is a Canaanite-Phoenician god of fertility and weather, specifically rainstorms. The name was also used as a title, however, meaning "Lord" and was applied to a number of different deities throughout the ancient Near East. Baal is best known today from the Bible as the antagonist of the Israelite cult of Yahweh.

Tales concerning Baal date back to the mid-14th and late 13th centuries BCE in written form but are understood to be much older, preserved by oral tradition until committed to writing. Excavations of the ancient city of Ugarit (modern-day Ras Shamra, Syria) beginning in 1929 CE revealed thousands of cuneiform tablets, many of them relating the tales of the gods and, specifically, Baal, who became king of the gods, replacing El.

Baal's popularity is attested by the many copies found of the stories that make up the so-called Baal Cycle which relates how Baal conquers death and assumes the kingship of the gods. The story of Baal's descent to the underworld and return has often been cited as an early example of the dying and reviving god motif but this has been challenged as Baal does not actually die and return to life.

The personal name Baal is also a theophoric name which could apply to many male deities throughout the Levant and Mesopotamia but is most frequently used to refer to Baal Hadad (also Ba'al Adad), the god of storms and rain in Canaanite and Mesopotamian religion who eventually became a war god as well. Baal Hadad is the central character of the Baal Cycle and also the god who appears in the biblical books of Exodus and I and II Kings where he is portrayed negatively. By the time of the Protestant Reformation (1517-1648 CE) he was regularly referenced as Beelzebub ("Lord of the Flies") and thought synonymous with the Christian devil. In the present day, interest in Baal has been revived by Neo-Pagan and Wiccan groups who often choose him as their personal deity in ritual worship.

Mesopotamian Origins

Baal Hadad originated in Mesopotamia under the names Adad in the north and Iskur in the south. He is attested as early as the time of the Akkadian Empire (2334-2218 BCE) but became more popular after the fall of the Third Dynasty of Ur (2047-1750 BCE) during the First Babylonian Empire (c. 1894 to c. 1595 BCE). Even so, at this time, he was not a major deity and was often associated with the storm god Ninurta as a subordinate or with the great god Enlil as a kind of personal secretary. It was during this time, however, that he came to be associated with the bull as his sacred animal, which would become a prominent aspect of his iconography later.

Baal was also linked with Shamash (as an arbiter of justice), with the moon goddess Nanna regarding fertility and harvests, and with Shala, a grain goddess. In time, he also became associated with Dagan (also given as Dagon), the Phoenician lord of the gods, owing to his earlier link with Enlil who had a similar role in Mesopotamia. At some point, he became central in divination rituals along with Shamash, most likely because both were associated with the concept of divine justice and so would ensure a fair response to one's supplications.

By the time Baal Hadad's worship reached Ugarit, he was a major deity understood as a sky god who brought rain and was a friend of the life-giving sun. He is referenced as the son of El, the king of the gods, in Ugarit and is said to live in a palace on Mount Zaphon. A stele from the site shows him with a club in one hand and a lightning bolt in the other, identifying him as a god of storms and war. He would be primarily associated with storms and rains throughout his worship in Ugarit and later after c. 1200 BCE when Ugarit was destroyed.

Baal in the Levant

While still a thriving city, however, Ugarit participated in trade with others including the major urban centers of the Levant. Baal Hadad seems to have traveled there via trade, though precisely when is unknown. He became a central deity of the Canaanite pantheon which would inform, first, Canaanite beliefs and, later, Phoenician religion. The Phoenician city of Baalbek (in modern-day Lebanon) was his cult center where he was worshipped with his consort Astarte, goddess of love, sexuality, and war (associated with the goddess Inanna/Ishtar, among others). Even so, Astarte was the most popular deity at Sidon, even eclipsing Baal in the number of temples dedicated to her, and is equally well represented at Baalbek.

The interpretation of the pairing of Baal and Astarte has been challenged for various reasons, among them the possibility that the goddess associated with Baal is his sister, Anat, who is thought to have informed the development of Astarte. This argument, however, seems to ignore her depiction in the Baal Cycle and other tales like El's Drinking Party (in which she is clearly differentiated from Anat) as well as her temples at Baalbek.

Phoenician religion developed the earlier Canaanite pantheon, possibly at Byblos, where the god El and goddess Baalat Gebel were most prominent along with the Greek deity Adonis who was associated with the Babylonian god Tammuz. Baal had a place among the other gods but was never as popular in cities outside of Sidon as other deities such as Melqart of Tyre (also a consort of Astarte), Dagon, Reshef (god of lightning and fire), Chusor (god of metallurgy) or the god of crafts, Kothar-wa-Khasis, who would feature prominently in the Baal Cycle. Even in Sidon, Baal was not the most prominent god as their patron deity was Eshmun. Still, he was popular enough to have inspired the Baal Cycle in which many of the gods appear. Yamm, god of the seas, and Mot, the god of death, were also closely associated with Baal through the stories about him which feature Astarte and other goddesses as well. Scholars Michael D. Coogan and Mark S. Smith comment:

Three goddesses appear regularly in the stories [about Baal] – Astarte, mentioned only in passing, Asherah, and Anat. The latter two have significant though not dominant roles in the myths, for Ugaritic theology, like Ugaritic society, was patriarchal. Asherah is El's consort and the mother of the gods. The only goddess with a vivid character is Anat. She is Baal's sister and is closely identified with him as a successful opponent of [Yamm, Mot] and other destructive powers. (7)

All three goddesses would come to be associated closely with Baal in the biblical narratives as Asherah is referenced as a sacred fertility pole (or possibly tree) in Deuteronomy 16:21, II Kings 21:7, II Kings 23:4, 6-7, and elsewhere. Prior to these works, however, she appears as El's consort and a central figure in the Baal Cycle.

The Baal Cycle

The Baal Cycle begins with Baal, son of Dagon, confident that he will be chosen as king by El, lord of the gods. El disappoints his expectations, however, by choosing Yamm, who almost instantly subjugates the other gods and forces them to work for him. The gods complain to Asherah who agrees to intercede for them with Yamm. She offers him all kinds of treasures, but he is only interested in possessing her. She agrees but must first return to El and the divine court to inform them of their contract.

Every god in attendance supports Asherah's decision to give herself to Yamm except Baal who swears revenge on Yamm for insulting Asherah in this way and promises to kill him. His reaction is interpreted as treason by some of the other gods who are quick to inform Yamm of it, and Yamm then sends emissaries to the court demanding Baal's surrender. The other gods show the emissaries the utmost respect, but Baal refuses to bow and is disgusted by the behavior of his fellow deities.

No decision is given by the gods and so Yamm sends a second delegation who are arrogant and neglect the proper rituals due to El and the court. Baal wants to kill them for this affrontery, but he is held back by Anat and Astarte, who warn him against the sin of killing a messenger who is only acting on orders and is therefore innocent. El does not move against the messengers either but, instead, promises them that Baal will not only appear before Yamm but will bring lavish gifts.

Baal is enraged but understands he is not powerful enough to defeat Yamm in single combat. Kothar-wa-Khasis suggests a way, however, and tells Baal he can create two clubs for him, Yagrush and Aymur, which will destroy Yamm if used as instructed. Kothar-wa-Khasis makes the weapons and tells Baal how to use them, and Baal goes to meet Yamm, bearing no gifts. He strikes Yamm on the shoulders with Yagrush, but Yamm is unhurt. Baal retreats and returns to strike Yamm with Aymur between the eyes, and Yamm falls. Baal then hauls him back to the court, announces his victory, and casts Yamm back into the sea.

Baal is now king of the gods, but Mot objects to this usurpation and sends the sea monster Lotan (possibly a form of Yamm) to attack Baal, but Baal defeats and kills him. Mot is now enraged further and swears he will devour Baal. Mot is unstoppable, and Baal understands that there are no magical weapons that can defeat death. He goes into hiding, sending a double in his place to be eaten by Mot, and all the gods mourn his death. As he was the god of rain and fertility, the earth becomes barren in his absence, and Anat, swearing revenge, attacks and kills Mot.

As Mot is immortal, he returns to life, but Baal then emerges from hiding and subdues him, forcing him to return to his underworld home and recognize Baal as the legitimate king. He then asks for and receives permission from El and the other gods for Kothar-wa-Khasis to build him a grand palace on a mountain top (initially with no windows since it was thought Mot-as-Death entered a dwelling through a window) and begins his reign.

The story is understood as illustrating a transition in power from the elder gods to a younger set, a familiar pattern in religious works of many different cultures as noted by Coogan and Smith:

The transfer of power from an older sky god to a younger storm god is attested in other contemporaneous eastern Mediterranean cultures. Cronus was imprisoned and succeeded by his son Zeus, Yahweh succeeded El as the god of Israel, the Hurrian god Teshub assumed kingship in heaven after having defeated his father Kumarbi, and Baal replaced El as the effective head of the Ugaritic pantheon. (104)

The story also touches on the theme of order vs. chaos explored in famous myths like the Enuma Elish from Mesopotamia and the Osiris-Set cycle from Egyptian mythology. In both, order is threatened, and it is only by conquering the forces of chaos that it can be restored. The definition of 'order' and 'chaos', however, depends on who is using those terms, and in ancient Israel, Baal would be cast in the role of the chaotic threat and Yahweh as the hero of a just and ordered world.

Baal in the Bible

Although Baal is mentioned almost 100 times in the Bible, he is best known from the narratives of I and II Kings which include the story of the Phoenician princess Jezebel (d. c. 842 BCE), who encouraged his worship, and her struggle with the prophet Elijah, champion of the cult of Yahweh. Jezebel marries the Israelite King Ahab, who, according to I Kings 16:30-33, is seduced by her into turning away from Yahweh to worship Baal. As Phoenician royalty and the daughter of a priest of Baal, Jezebel would have naturally brought her own gods to her new home, but according to the narrative, these were rejected by the adherents of the Yahweh cult.

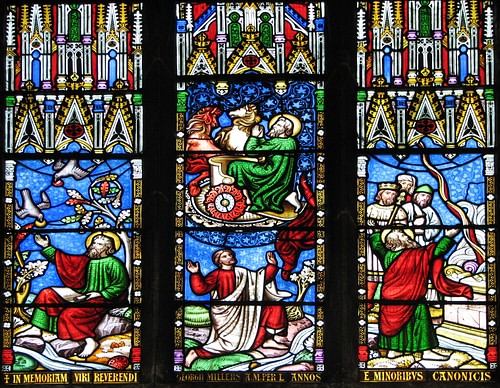

Jezebel and Elijah spar with each other for the supremacy of their respective faiths until they agree the matter will be settled by a duel between the gods themselves at the top of Mount Carmel. Jezebel's priests will call on Baal and Elijah on Yahweh, and whichever god responds by lighting the fire under a sacrificial bull will be recognized as the one true god. The factions gather at Mount Carmel, and 850 priests of Baal call on him all day as they dance around the altar (I Kings 18:26) while Elijah mocks them by asking where their god is and why he is not answering. When it is Elijah's turn, he calls out to Yahweh, and fire comes down from heaven instantly, lighting the altar and consuming the offering (I Kings 18: 38-39). Elijah proclaims Yahweh the winner and orders the priests of Baal to be executed.

Jezebel refuses to acknowledge this victory, however, and continues to encourage the worship of Baal, as well as swearing revenge on Elijah, until she is killed on the orders of General Jehu. Afterwards, the cult of Yahweh proclaims him the only god, and the temples and shrines to Baal, Astarte, and the other Canaanite gods are destroyed. Baal worship in Israel continues, however, in later narratives which illustrate the struggle between traditional polytheism and emerging monotheism in the region in the 9th century BCE.

Conclusion

Baal's cult was eventually replaced by the cult of Yahweh and his name became synonymous with the enemies of the one true god. In II Kings 1, Ba'al Zebub is associated with Ekron, god of the Philistines, the people famously cast as the enemies of Israel in the Bible. Ba'al Zebub would eventually be known as Beelzebub to the New Testament scribes and linked with the Christian devil, an association that would last up through the time of the Protestant Reformation.

By that time, Baal had also come to be associated with the figure of Iblis, the devil in Islam, through passages in the Quran. Allah, in Islam, and Yahweh, in Judaism and Christianity, were recognized by their respective adherents as the only god and Baal as an aspect of chaos, darkness, and evil who threatened world order.

Initially, however, Yahweh was part of the same pantheon that embraced Baal, and the two would have been regarded as co-workers in the cause of order against the forces of chaos. Scholars J. Maxwell Miller and John H. Hayes comment:

Archaeological evidence indicates an essentially continuous religious and cultic scene throughout Palestine during the Early Iron Age. Nothing has been discovered, in other words, that suggests any notable distinctiveness in temple layout or cultic furniture for the time and territory of the early tribes. Continuity between early Israelite religion and that of the other inhabitants of Syria-Palestine is confirmed further by parallels between the religious and cultic terminology of the biblical materials and the corresponding terminology of extrabiblical documents. Elements of Syro-Palestinian mythology, such as a divine struggle with the cosmic dragon of chaos, also appear here and there in biblical poetry. Occasional biblical passages suggest, in fact, that Yahweh was once viewed as a member of the large pantheon ruled over by El. (111)

In order for Yahweh to be recognized as the supreme god, however, his predecessors had to be eliminated, and Baal was demonized in accomplishing this end. In the present day, the god's reputation as a powerful protector and life-affirming agency has been revived through the Neo-Pagan and Wiccan movements who reject the biblical narratives and rely on older constructs like the Baal Cycle. Although hardly widespread, the worship of Baal continues in the present day alongside the more popular Yahweh, mirroring the similar relationship the two gods had in the ancient world.