Babylon is the most famous city from ancient Mesopotamia whose ruins lie in modern-day Iraq 59 miles (94 km) southwest of Baghdad. The name is derived from bav-il or bav-ilim, which in Akkadian meant "Gate of God" (or "Gate of the Gods"), given as Babylon in Greek. In its time, it was a great cultural and religious center.

The city was referenced with awe by ancient Greek writers and was reportedly the site of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Its reputation has been tarnished by the many unfavorable references to it in the Bible beginning with Genesis 11:1-9 and the story of the Tower of Babel associated with the ziggurat of Babylon.

The city also appears unfavorably in the books of Daniel, Jeremiah, Isaiah, and, most famously, the Book of Revelation. Scholar Paul Kriwaczek notes that Babylon "can blame her evil repute squarely on the Bible" (167). Although none of these narratives speak well of the city, they were ultimately responsible for its fame (or infamy) in the modern age, which led to its rediscovery by the German archaeologist Robert Koldewey in 1899.

Babylon was founded at some point prior to the reign of Sargon of Akkad (the Great, 2334-2279 BCE) and seems to have been a minor port city on the Euphrates River until the rise of Hammurabi (r. 1792-1750 BCE), who made it the capital of his Babylonian Empire. After Hammurabi's death, his empire quickly fell apart. The city was sacked by the Hittites in 1595 BCE and then taken by the Kassites who renamed it Karanduniash.

It was briefly ruled by the Chaldeans (9th century BCE), whose name became synonymous with Babylonians to later Greek writers (notably Herodotus) and biblical scribes, and then was controlled by the Neo-Assyrian Empire (912-612 BCE) before being taken by Nabopolassar (r. 626-605 BCE), who established the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Babylon fell to the Persians under Cyrus II (the Great, r. c. 550-530 BCE) and was a capital of the Achaemenid Empire (550-330 BCE) until it fell to Alexander the Great in 331 BCE.

It continued as a trade center under the later Seleucid Empire (312-63 BCE), Parthian Empire (247 BCE to 224 CE), and Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE) but never attained the heights it had known under Hammurabi or the Neo-Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 605/604-562 BCE). The city declined after the Muslim Arab conquest in the 7th century CE and was finally abandoned.

It was known only through biblical narratives and classical writers until its discovery in the 19th century. In the 1980s, restoration attempts were made under then-president Saddam Hussein including a reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate (the actual gate presently in the Pergamon Museum of Berlin, Germany). In 2019, the ruins of the great city were declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Port City & Hammurabi

The earliest mention of the city comes from an inscription from the time of Sargon of Akkad. It seems to have been a small, but profitable, port city on the river by this time. Under the later Akkadian king Shar-Kali-Sharri (r. 2223-2198), it is recorded that two temples were built at Babylon, and it later fell under the control of the city of Kazallu until liberated by the Amorite chieftain Sumu-abum (r. c. 1895 BCE) whose successor, Sumu-la-ilu (also given as Suma-la-El, r. 1880-1845 BCE), was founder of the first dynasty of kings in Babylon. The city was still a small port at this time, overshadowed by neighboring city-states.

King Sin-Muballit (r. 1812-1793 BCE) beautified the city but could not elevate it above the others and finally led a military campaign against the most powerful of the neighboring city-states, Larsa, but was defeated. He was forced to abdicate in favor of his son, Hammurabi, who quietly submitted to the king of Larsa and busied himself with strengthening Babylon's walls and beautifying the city while, secretly, building and training an army.

When Larsa called on him to supply troops to repel the invading Elamites, Hammurabi complied but, as soon as the region was secured, he took the cities of Isin and Uruk from Larsa, formed alliances with Lagash and Nippur, and conquered Larsa completely. He then continued his campaigns, issuing his law codes, conquering Mesopotamia, and establishing his empire.

The Code of Hammurabi is well known but is only one example of the policies he implemented to maintain peace and encourage prosperity. He enlarged and heightened the walls of the city, engaged in great public works, which included opulent temples and canals, and made diplomacy an integral part of his administration.

So successful was he in both diplomacy and war that, by 1755 BCE, he had united all of Mesopotamia under the rule of Babylon which, by this time, was a major city and the largest in the world with a population at well over 100,000. The city was so powerful and famous after Hammurabi's conquests that all of southern Mesopotamia came to be called Babylonia.

The Assyrians & Nebuchadnezzar II

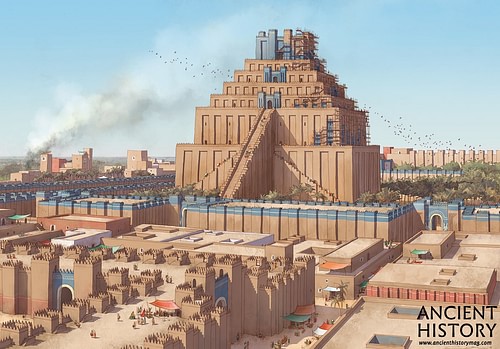

Following Hammurabi's death, his empire fell apart and Babylonia dwindled in size and scope until Babylon was easily sacked by the Hittites in 1595 BCE. The Kassites followed the Hittites and renamed the city Karanduniash. At some point between the 14th and 9th centuries BCE, the great ziggurat of Babylon was built which would later become associated with the Tower of Babel. This connection is thought to have been made owing to a misinterpretation of the Akkadian bav-il (Gate of the Gods) for the Hebrew bavel (confusion).

In the Genesis story, the people hope to make a name for themselves to be remembered after death and so begin to build a great tower to reach the heavens. God is angered by this as he worries that, if the people are allowed to reach their goal, they will then be empowered to attempt others and so disrupt the natural order. He therefore decrees they shall no longer speak the same language, confuses their tongues, and since they cannot understand each other anymore, the tower is left unfinished. Scholar Samuel Noah Kramer explains the story as an attempt to account for the many ziggurats, including Babylon's, found in ruin and seen by or described to Hebrew scribes (Sumerians, 293-294).

The Assyrians followed the Kassites in dominating the region, and under the reign of the king Sennacherib (r. 705-681 BCE), Babylon continually revolted. Sennacherib finally lost patience in 689 BCE and had the city sacked, razed, and the ruins scattered as a lesson to others. His extreme measures were considered impious by the people generally and Sennacherib's court specifically, and he was soon after assassinated by his sons, who justified the act as revenge for the desolation of Babylon.

His successor, Esarhaddon (r. 681-669 BCE), initiated the efforts to return Babylon to its former glory, personally overseeing the work. The city later rose in revolt against his successor, Ashurbanipal (r. 668-627 BCE), who put down the rebellion but did not damage Babylon to any great extent and, in fact, personally purified the city of the evil spirits which were thought to have led to the trouble. The reputation of the city as a center of learning and culture was already well-established by this time.

After the fall of the Assyrian Empire, the Chaldean king Nabopolassar took the throne of Babylon and, through careful alliances, created the Neo-Babylonian Empire. His son, Nebuchadnezzar II, renovated the city so that it covered 900 hectares (2,200 acres) of land and boasted some of the most beautiful and impressive structures in all of Mesopotamia.

Every ancient writer to make mention of the city of Babylon, save for the biblical scribes, references it with awe in describing the great ziggurat Etemenanki – "the foundation of heaven and earth" – the immense walls, the Ishtar Gate, and the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Herodotus comments on the city's size:

The city stands on a broad plain, and is an exact square, a hundred and twenty stadia in length each way, so that the entire circuit is four hundred and eighty stadia. While such is its size, in magnificence there is no other city that approaches to it. It is surrounded, in the first place, by a broad and deep moat, full of water, behind which rises a wall fifty royal cubits in width and two hundred in height. (I.178)

Although it is generally believed that Herodotus greatly exaggerated the dimensions of the city (and may never have actually visited the place himself), his description echoes the admiration of other writers of the time who recorded the magnificence of Babylon, and especially the great walls, as a wonder of the world. It was in the Neo-Babylonian Period, under Nebuchadnezzar II's reign (which also saw the beginning of the Babylonian Captivity of the Jews), that the Hanging Gardens of Babylon are said to have been constructed and the famous Ishtar Gate built. The Hanging Gardens are most explicitly described in a passage from Diodorus Siculus (l. 90-30 BCE) in his work Bibliotheca Historica Book II.10:

There was also, because the acropolis, the Hanging Garden, as it is called, which was built, not by Semiramis, but by a later Syrian king to please one of his concubines; for she, they say, being a Persian by race and longing for the meadows of her mountains, asked the king to imitate, through the artifice of a planted garden, the distinctive landscape of Persia. The park extended four plethra on each side, and since the approach to the garden sloped like a hillside and the several parts of the structure rose from one another tier on tier, the appearance of the whole resembled that of a theatre. When the ascending terraces had been built, there had been constructed beneath them galleries which carried the entire weight of the planted garden and rose little by little one above the other along the approach; and the uppermost gallery, which was fifty cubits high, bore the highest surface of the park, which was made level with the circuit wall of the battlements of the city. Furthermore, the walls, which had been constructed at great expense, were twenty-two feet thick, while the passage-way between each two walls was ten feet wide. The roofs of the galleries were covered over with beams of stone sixteen feet long, inclusive of the overlap, and four feet wide. The roof above these beams had first a layer of reeds laid in great quantities of bitumen, over this two courses of baked brick bonded by cement, and as a third layer a covering of lead, to the end that the moisture from the soil might not penetrate beneath. On all this again earth had been piled to a depth sufficient for the roots of the largest trees; and the ground, which was levelled off, was thickly planted with trees of every kind that, by their great size or any other charm, could give pleasure to beholder. And since the galleries, each projecting beyond another, all received the light, they contained many royal lodgings of every description; and there was one gallery which contained openings leading from the topmost surface and machines for supplying the garden with water, the machines raising the water in great abundance from the river, although no one outside could see it being done. Now this park, as I have said, was a later construction.

This part of Diodorus' work concerns the semi-mythical queen Semiramis (probably based on the actual Assyrian queen Sammu-Ramat, r. 811-806 BCE). His reference to "a later Syrian king" follows Herodotus' tendency of referring to Mesopotamia as 'Assyria'. Recent scholarship on the subject argues that the Hanging Gardens were never located at Babylon but were instead the creation of Sennacherib at his capital of Nineveh. Scholar Christopher Scarre writes:

Sennacherib's palace [at Nineveh] had all the usual accoutrements of a major Assyrian residence: colossal guardian figures and impressively carved stone reliefs (over 2,000 sculptured slabs in 71 rooms). Its gardens, too, were exceptional. Recent research by British Assyriologist Stephanie Dalley has suggested that these were the famous Hanging Gardens, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Later writers placed the Hanging Gardens at Babylon, but extensive research has failed to find any trace of them. Sennacherib's proud account of the palace gardens he created at Nineveh fits that of the Hanging Gardens in several significant details. (231)

If the gardens were in Babylon, they would have been part of the central complex of the city. The Euphrates River divided the city in two between an old and new city, with the Temple of Marduk and the great towering ziggurat in the new, where, most likely, the gardens would have also been located. Streets and avenues had been widened under Esarhaddon to better accommodate the yearly processional of the statue of the great god Marduk in the journey from his home temple in the city to the New Year Festival Temple outside the Ishtar Gate, and these were further improved upon by Nebuchadnezzar II.

The Persian Conquest

The Neo-Babylonian Empire continued after the death of Nebuchadnezzar II, and Babylon remained a significant city under Nabonidus (r. 556-539 BCE), known as "the first archaeologist" for his restoration efforts of older sites (such as the ziggurat of Ur). In 539 BCE, the empire fell to the Persians under Cyrus the Great at the Battle of Opis. Babylon's walls were impregnable and so the Persians cleverly devised a plan whereby they diverted the course of the Euphrates River so that it fell to a manageable depth.

While the residents of the city were distracted by one of their great religious feast days, the Persian army waded the river and marched under the walls of Babylon unnoticed. It was claimed the city was taken without a fight, although documents of the time indicate that repairs had to be made to the walls and some sections of the city and so perhaps the action was not as effortless as the Persian account claimed.

Under Persian rule, Babylon flourished as a center of art and education. Cyrus and his successors held the city in great regard and made it one of the administrative capitals of their empire. Babylonian mathematics, cosmology, and astronomy were highly respected, and it is thought that Thales of Miletus (l. c. 585 BCE) studied there and that Pythagoras (l. c. 571 to c. 497 BCE) developed his famous mathematical theorem based upon a Babylonian model.

Conclusion

After the Achaemenid Empire fell to Alexander the Great in 331 BCE, he continued a respectful treatment of the city, ordering his men not to damage the buildings or molest the inhabitants. He hoped to beautify and restore the city but died before his plans could be implemented. Scholar Stephen Bertman notes:

Before his death, Alexander the Great ordered the superstructure of Babylon's ziggurat pulled down in order that it might be rebuilt with greater splendor. But he never lived to bring his project to completion. Over the centuries, its scattered bricks have been cannibalized by peasants to fulfill humbler dreams. All that is left of the fabled Tower of Babel is the bed of a swampy pond. (14)

After Alexander's death at Babylon in 323 BCE, in the Wars of the Diadochi, his successors fought over his empire generally and the city specifically to the point where the residents fled for their safety (or, according to one ancient report, were relocated). By the time the Parthian Empire ruled the region, Babylon was a poor version of its former self. The city steadily fell into ruin and, even during a brief revival under the Sassanian Empire, never approached its former greatness.

In the Muslim conquest of the land, in 651 CE, whatever remained of Babylon was swept away and, in time, was buried beneath the sands. In the 17th and 18th centuries, European travelers began to explore the area and returned home with various artifacts of interest. In the 19th century, European museums, and institutes of higher learning, hoping to find archaeological evidence for biblical narratives, sponsored several expeditions to the region which unearthed many of the greatest Mesopotamian cities; among them was Babylon, the once-mighty Gate of the Gods.