Brennus (c. 390 BCE) was the Gallic war chief of the Senones who sacked and occupied Rome in 390 BCE. Nothing is known of him outside of the accounts given of this event which immortalized him as coining the phrase, “Woe to the Vanquished” when the conquered Romans complained he acted unjustly at their surrender.

The story of Brennus and his invasion is told by a number of Roman historians (Livy, Polybius, and Plutarch) writing centuries later who drew on earlier, original sources no longer extant. According to these historians, the Senones were first engaged in a siege of the nearby city of Clusium, to the north of Rome by about 75 miles (c. 120 km), and the citizens appealed to Rome for help. A delegation of Romans arrived but insulted the honor of the Senones who then left Clusium to attack Rome. They encountered the Roman army at the River Allia and defeated them, forcing the Roman citizens to flee the city en masse.

Brennus took Rome without resistance, but a small band of defenders had fortified themselves on the Capitoline Hill and Brennus was forced to lay siege to dislodge them. He was finally defeated by Marcus Furius Camillus (d. 365 BCE) who arrived with a force gathered from nearby cities. Brennus is assumed to have been killed in the battle which followed his exit from Rome as there is no further record of him.

Senone Activity in Italy

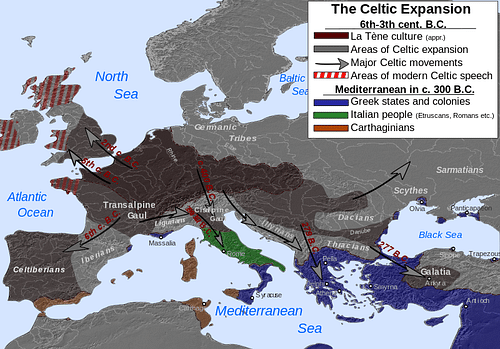

The Senones arrived in Italy at some point in the early 4th century BCE and settled on the east coast. Nothing is known concerning their motivation for crossing the Alps into Italy, but Plutarch claims they were driven by their love of Italian wine and came “in quest of the land which produced such fruit, considering the rest of the world barren and wild” (Life of Camillus, 15.2). Plutarch also records the story of an Italian man whose wife was unfaithful to him who sought out and led the Senones into Italy in revenge as well as the theory that they left Gaul simply because it was overpopulated.

Once arrived, the Senones founded the city of Sena Gallica on the coast (modern-day Senigallia) after driving the Umbrians from the region. They engaged in trade with settlements such as Massilia and Etruria and founded further settlements, with Sena Gallica as their capital. Their obvious success in battle against the Umbrians gained them a reputation among the cities and towns of Italy as fierce fighters, and they were frequently hired as mercenaries in different armies.

As they moved up and down the country, fighting for one settlement against another and returning to Sena Gallica, they brought back reports of rich and fertile lands further down the coast and this encouraged some groups to migrate south and some raiding parties to seize the lands of others.

In time, one such group of Senones, led by the war-chief Brennus, came to the city of Clusium. There seems some discrepancy in the original sources Livy and the others drew from regarding their motivation. It is possible they were originally invited to come as mercenaries to fight for one political party in Clusium against a rival or were asked to fight for Clusium against another city and then turned on Clusium itself, but this is unclear.

Plutarch claims that they were seeking land and, seeing there was plenty around the city which seemed unclaimed, asked the Clusians if they could obtain rights to farm and live there. The Clusians were not inclined to share and asked the Senones to move on. The Senones then lay siege to the city, and the Clusians appealed to Rome for help.

Rome & Clusium

Rome was not an ally of Clusium and had no interest in becoming one. The Romans had only recently won a long, drawn-out, ten-year war with the neighboring city of Veii, which had been conquered by the general Camillus, and they were tired of conflict. Camillus had also put down a number of other threats in the region and, although he had won every engagement, had naturally incurred losses, and Rome was not interested in risking more men for a city of strangers.

Further, there was no military leader in Rome at the time who would take on the command of such an expedition. Camillus, after winning the war with Veii and bringing the spoils back to Rome, as well as defeating other cities and tribes in the region, was banished by the Senate for alleged misconduct after the war. Camillus had proven himself a brilliant strategist and charismatic leader, and there seemed no others who could take his place after he left the city for exile in the town of Ardea.

Rome, therefore, had neither the interest nor anyone they could send who could relieve the siege of Clusium but, feeling they should do something, they sent three brothers of the patrician Fabii family as ambassadors to negotiate a peace. The Fabii spoke with the Senone leadership, asking them to lift the siege and move on and cautioned them that, if they did not, Rome might become involved. They asked the Senones what wrong the Clusians had done them to warrant this attack on the city and, according to Plutarch, Brennus answered:

The Clusians wrong us in that, being able to till only a small parcel of earth, they yet are bent on holding a large one, and will not share it with us, who are strangers, many in number and poor. This is the wrong which ye too suffered, O Romans, formerly at the hands of the Albans, Fidenates, and Ardeates, and now lately at the hands of the Veientines, Capenates, and many of the Faliscans and Volscians. Ye march against these peoples, and if they will not share their goods with you, ye enslave them, despoil them, and raze their cities to the ground; not that in so doing ye are in any wise cruel or unjust, nay, ye are but obeying that most ancient of laws which gives to the stronger the goods of his weaker neighbours, the world over, beginning with God himself and ending with the beasts that perish. For these too are so endowed by nature that the stronger seeks to have more than the weaker. Cease ye, therefore, to pity the Clusians when we besiege them, that ye may not teach the Gauls to be kind and full of pity towards those who are wronged by the Romans. (Life of Camillus, 17.2-4)

The Fabii brothers recognized that further talks were useless and so left the Senones and went into Clusium where they encouraged the Clusians to take up arms and drive the Senones off by force. The Clusians launched an attack, and the Fabii brothers joined them. One of the brothers, Quintus, killed a Gallic chief, and when he stopped to strip off the man's armor, he was recognized by Brennus who accused him, rightly, of breaking the laws of nations at war because he had come as an ambassador of peace but had taken up arms instead. Brennus called a halt to the siege and sent a delegation to Rome demanding that the brothers be arrested and turned over to them.

The Battle of the Allia

There were many Romans, according to multiple sources, who were sympathetic to the Senone claim and wanted Quintus handed over; but there were others, with greater power, who could not support this decision. Not only was Quintus not arrested but he and one of his brothers were appointed as military tribunes. The Senone ambassadors were outraged and declared that their battle was no longer with Clusium but only with Rome.

The Senones marched the distance from Clusium through a number of highly populated areas but never touched a single town or city. Brennus assured the people that his fight was not with them and his men would not harm them in any way; he was only intent on Rome. The Romans were warned by the Clusians that the Senones were on their way to Rome but had so little regard for their opponents that, according to Livy, they did not bother to make the proper offerings to the gods for victory nor consult the oracles; they were confident they would make short work of the marauding barbarian tribe.

The army was mobilized and marched out to meet the enemy at the Allia River. They did not bother to position their camp with any security, erected no defenses, dug no trenches, and, as Livy writes, “had shown as much disregard of the gods as of the enemy, for they formed their order of battle without having obtained favorable auspices” (5.38). They extended their line fully on either wing, leaving the center thin, and placed their reserves – who were new recruits with no experience – in back of the line on the right. Their forces numbered around 15,000 facing a Senone force of over 30,000.

When Brennus gave his war cry, the Senones advanced, and the Romans closed in a phalanx position, but Brennus was concerned that the Roman reserves might move to outflank him and so directed his cavalry charge not at the center but to the right targeting the reserves. The new recruits broke formation under the onslaught and fled, and the line crumbled. Panic swept through the Roman army as the Senones charged through their lines, and as Livy observes, “none were slain while actually fighting; they were cut down from behind whilst hindering one another's flight in a confused, struggling mass” (5.38). Survivors fled to Veii or any other place of safety from which they could make their way back to Rome, but only a third or less of the Roman army survived the Battle of Allia.

The Siege of Rome

Brennus must have been surprised by his incredible good fortune and gave his men free rein to strip the corpses for weapons and celebrate their victory. Had he given the order to instantly pursue survivors and march on Rome the final outcome of his war would probably have gone differently, but, as it was, he allowed those who had escaped to bring word of the defeat to the city.

Many of the citizens fled but a group of soldiers took up position on the Capitoline Hill, and the treasures of the city, especially the eternal flame, was hurriedly carried out by the Vestal Virgins along with a number of sacred artifacts. The senators, refusing to leave or take refuge on the hill, dressed in their finest robes and awaited the Senones in the forum.

When Brennus and his army arrived, the gates of Rome were hanging open and there was no defense in sight. Fearing a trap, he entered cautiously but found no one but the senators who were quickly killed. He ordered a sack of the city and set his warriors loose before he discovered the defenders on the hill. Although he tried to dislodge them, he failed and so settled in for a siege.

Camillus & Brennus

The Roman defenders were well entrenched and so the siege dragged on and food became scarce for the Senones. While a force remained in Rome to keep the siege, raiding parties were sent out to sack the nearby towns and cities for supplies, and one of these came to Ardea where Camillus was living in exile. He appealed to the town elders to allow him to lead a defense of the city and, this granted, armed the men and led them toward the nearby Senone camp by night. His surprise attack was a success and few Senones survived; those who did were found wandering the fields the next morning and were killed.

News of Camillus' victory reached the Roman survivors of Allia at Veii and they asked Camillus to lead them in battle against the force besieging Rome. Camillus, however, refused, as he did not have the consent of the men of Rome and it would be illegal for him to lead an armed force into the city without their authorization. There seemed no way to get this, however, since the city was occupied.

A young man named Pontius Cominius volunteered to sneak into Rome, deliver their plea to the Romans on the hill, and return. He snuck through the enemy lines by night, scaled the outer part of the Capitoline Hill and, after identifying himself to the sentries, was pulled over the wall. He received approval for the plan and departed the same way he had come, returning safely to give Camillus the news.

On his climb up and down the hill, however, Cominius had dislodged some rocks and torn up some bits of turf which the Senones noticed and reported to Brennus. He recognized that his enemies had just shown him a way to end the siege and so ordered a night raid whereby his men would scale the cliff just as Cominius had and come upon the defenders from behind.

The Senone warriors climbed the hill quietly while the defenders, and even the watchdogs, were sleeping and their plan would have succeeded but the sacred geese of Juno, kept on the hill, were awake and began crying out as the Senones reached the top. Their cries alerted the defenders and one of them, Manlius, quickly took up his arms and attacked. The Senones were driven back, many of them falling from the cliff as they were struck by those dropping from above, and so Brennus' plan was foiled.

Although the Romans celebrated their victory, they realized they were still in a dire position as they were running out of food. The Senones were also becoming desperate because, ever since Camillus' victory over the raiders at Ardea, they were afraid to send out more parties to forage for food. The Roman tribune Sulpicius, therefore, asked for a parley with Brennus to end the siege and it was agreed that the Romans would pay the Senones 1,000 pounds of gold to leave the city.

When the money was to be paid, however, the Senones brought their own weights which the Romans claimed were unfairly balanced, meaning the Romans would be paying more than what was agreed to. When they complained, Brennus is said to have thrown his sword and belt onto the scales and, when Sulpicius asked him what that meant, he replied, “Woe to the vanquished.”

According to Plutarch's account, it was at this point that Camillus entered the city with his army (other historians vary on this) and made his way to the negotiations. He took the gold off the scales and gave it to his attendants, telling Brennus that Rome would be delivered by iron and not by gold. Brennus was enraged, complaining that he had already concluded a deal with the Romans, but Camillus told him that the deal was not binding because he was the only legal authority who could have authorized it and, clearly, had not.

Fighting broke out between the Senones and the Romans in the streets but, realizing he could not form his soldiers efficiently for battle, Brennus led his men out of the city for better ground. Camillus followed him with his forces, and the Senones were defeated. Brennus is assumed to have been killed in this battle, and the survivors were scattered.

Conclusion

Camillus was hailed as the “second founder of Rome” and a “second Romulus” for his victory and would continue to serve Rome as statesman and soldier, chosen as dictator five times in his life until he died of the plague in 365 BCE. He is the first great general in Roman history who is historically attested, but even so, it is commonly understood that the Roman writers embellished on his story as found in the original sources to make them more interesting.

Even so, no modern historian doubts that Brennus sacked Rome in c. 390 BCE and that Camillus was instrumental in driving him from the city; scholars do, however, disagree on the accuracy of some details of the accounts. Some scholars, such as Stephen A. Stertz, contend that Camillus never engaged in battle with Brennus and actually paid the 1,000 pounds in gold for him to leave Rome, but this opinion is in the minority. The devastation of the city as described has been challenged by modern-day archaeology which has found no evidence of the kind of destruction these writers detail dating to c. 390 BCE.

Even though the actual event may not have been as devastating as described, however, there is no doubt it was remembered that way. The sack of Rome in 390 BCE, as well as the Battle of the Allia River, marked the anniversary dates as unlucky days in the Roman calendar (sometime in mid-July, possibly the 18th). To the Romans, the event was an unthinkable tragedy of extraordinary proportions: the first time in their history that the city was taken and occupied by an enemy army.

Whether the actual event corresponds closely to the later accounts ceased to matter centuries ago. Whatever Brennus' final fate actually was, and whether Camillus defeated him or paid him to leave, the story as told by Livy and Plutarch records what the people of Rome claimed to have happened, and such claims, repeated through time, became history.