Ancient Britain was a landmass on the northwest of the continent of Europe first occupied by humans c. 800,000 years ago prior to it becoming an island c. 6000 BCE due to flooding which separated it from the mainland. Agriculture began to develop in the region c. 4200 BCE encouraging the development of civilization.

The earliest evidence of humans in the area is dated to between 800,000-700,000 years ago with Neanderthals appearing c. 400,000 years ago and Homo sapiens c. 12,000 years ago. The early hunter-gatherer societies became sedentary by c. 4,200 BCE during the Neolithic Period, but the daily lives of these people are known only through archaeological evidence as they left no written record. Migrations such as those of the people of the Bell Beaker Culture (c. 2500 BCE) influenced a change in the cultural norms, as evidenced by ceramics, as the later Celtic migration would do also.

The region was known to the Mediterranean world through reports by Phoenician traders who regularly traveled there, and the first written mention of 'Britain' appears in 325 BCE in the work On the Ocean: the famous voyage of Pytheas of Massalia (modern-day Marseille, France), a Greek explorer. Nothing was known of the interior of Britain until its conquest by the Romans beginning in 43 CE. After the Romans left in 410 CE, other peoples arrived such as the Anglo-Saxons, who further impacted the social structure, religion, and culture of the Britons.

This paradigm continued with the arrival of the Vikings in 793, the rise of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in response to the invaders, and the Norman conquest of England in 1066. By this time, 'Ancient Britain' had already passed through the stage historians refer to as 'Late Antiquity' and was approaching the Early Modern Period, usually dated as beginning c. 1500.

Prehistoric Britain

The region that would become known as 'Britain' is the southern area of the modern-day United Kingdom of Scotland, Wales, and Britain (excluding Northern Ireland) and was attached to the continent of Europe during the Paleolithic Period when the first hominids arrived. Homo erectus appeared in the region c. 600,000 years ago and Neanderthals by c. 400,000 years ago. Fire had already been discovered by the time of Homo erectus who created hearths to light and warm their cave dwellings. Neanderthals seem to have built on earlier developments of rudimentary tools and also used fire for heat, warmth, and cooking. Neanderthal culture included many aspects of later civilization including local and long-distance trade, grave goods, textile production, and art.

Homo sapiens appear in Europe c. 50,000 years ago and in Britain c. 12,000 years ago. The regions later known as Britain and Albion (Scotland) became an island c. 6000 BCE when landslides in Norway launched a huge tsunami which turned the south-eastern low-lying area into what is now known as the English Channel. The submerged area (referred to by modern scholars as Doggerland), according to recent studies (2020), may have at first been turned into several islands before rising sea levels sank them as well, separating those who had migrated to Britain from the rest of Europe.

These hunter-gatherer communities lived a nomadic or semi-nomadic existence until c. 4200 BCE when the paradigm shifted toward agriculture and permanent settlements during the Neolithic Period. This era saw the creation of megalithic monuments, tombs, and sites which have been interpreted as temples, with Stonehenge as the best known, dated to between c. 3000-2400 BCE. The Bronze Age began in Britain c. 2500-2100 BCE when bronze items begin to appear in the archaeological record and, at about this same time, the people of the Bell Beaker Culture appear.

The Bell Beaker people (so named for the type of ceramics they created) migrated to Britain from Europe by sea, but no one knows why. They seem to have placed greater emphasis on the individual as evidenced by the ornamentation on their ceramics and the kinds of items used as grave goods which included the deceased's weapons. The Celts arrived in the region c. 900 BCE and, by 600 BCE, had perfected the architecture known as the hillfort. Hillforts suggest tribal, or at least communal/regional, identity and conflict between different settlements, most likely over natural resources.

Mediterranean Contact

The Phoenicians of Carthage were in contact with the people of Britain from as early as c. 450 BCE when an expedition led by Himilco arrived there to trade for tin needed in making bronze. The Phoenicians traded with the coastal peoples and were the first to bring news of Britain to the Greeks, with whom they also traded. In 325 BCE, Pytheas explored the coastline of Britain and was the first to name the island 'Britain' (Bretannike) meaning 'painted' and referring to the people's custom of painting (or tattooing) themselves. His name for the people collectively (Pritani, which became Britanni) gave them the name Britons.

Pytheas' work, On the Ocean, is no longer extant but was referenced repeatedly by later writers. Scholar Barry Cunliffe notes:

The scraps that survive of Pytheas' account are the earliest descriptions we have of Brittany, the British Isles, and the eastern coasts of the North Sea – they represent the beginnings of northwest European history and the first glimpse the British have of their ancestors. (viii)

These ancestors were the over 20 different tribes of Britain and included the Atrebates and the Catuvellauni, who would both play significant roles in Britain's future, as would the Iceni and many others through their interactions and relations with Rome.

Roman Britain

The Romans had known of Britain since at least the 4th century BCE via Phoenician and Greek traders but had no direct contact with the Britons until Julius Caesar crossed the Channel from Gaul in 55 BCE. Caesar had no siege engines, and his ships had been damaged in the crossing, so he was not prepared for any major engagements and withdrew. He returned in 54 BCE and established diplomatic relations with some of the tribes, notably the Atrebates and Catuvellauni.

Rome supported these tribes in their conflicts with others in return for trading rights, but the Roman government had no real interest in their welfare, only in maintaining the balance of power necessary for trade. Roman emperor Augustus (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE) considered expeditions to conquer Britain and seize the resources but never acted on his plans. In the early 40s CE, Verica, the king of the Atrebates, was defeated by Caratacus, king of the Catuvellauni, and fled Britain, asking for assistance from Rome. Caligula (r. 37-41 CE) mobilized a force to send against the Atrebates but failed to launch it, and so the emperor Claudius (r. 41-54 CE), recognizing the value of Augustus' earlier plans and using Verica as an excuse, sent a large invasion force against Britain in 43 CE under the general Aulus Plautius.

The Catuvellauni met the invasion force in southern Britain, probably near modern-day Kent, at the Battle of Medway and were defeated. The Roman forces then divided in different directions under separate commanders to subdue the other tribes and bring Britain under the control of the Roman Empire. Cities including Camulodunum (Colchester), Eboracum (York), Lindum Colonia (Lincoln), Verulamium (St. Albans), and Londinium (London) were established relatively quickly with Colchester as the first to be given the status of a Roman colonia in 49 CE.

The path to conquest was not smooth, however, as Caratacus rallied the tribes against the Roman invaders repeatedly until his defeat and capture in 51 CE. Other tribes continued resistance against Rome, but the most famous was the revolt of Boudicca, queen of the Iceni, in 60/61 CE during the reign of Nero (54-68 CE). Boudicca was the wife of the Iceni king Prasutagus, an ally of Rome, who divided his estate between his daughters and Nero. When he died, Rome refused to honor his will, and when Boudicca objected, she was flogged, and her two daughters were raped.

Boudicca rallied the Iceni and other tribes against Rome, destroying the cities of Colchester, St. Albans, and Londinium before she was defeated by the Roman governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus at the Battle of Watling Street in 61 CE. This victory for the Romans did not end resistance, however, and the general Agricola continued the conquest, bringing the fight to the Picts of the north and defeating them at the Battle of Mons Graupius in 83 CE. Agricola was recalled to Rome after the battle and no other general had any lasting success in extending the northern border of Roman Britain, which was defined in 122 CE by Hadrian's Wall.

The Britons, especially those who wished to benefit from bureaucratic positions in Roman trade and government, adopted Roman dress, culture, and language in cities like Londinium – which became an administrative capital – and supported Roman initiatives such as roads, aqueducts, public parks and buildings, temples, forums, arenas, and Roman baths.

The province of Britain developed into a vital resource for the Roman Empire even though, as an island with ports along the coast, it was vulnerable to raids by Saxon pirates as well as the ships of the Franks launched from Gaul across the Channel. Saxon and Frankish raids by sea and incursions by the Picts of the north weakened Rome's resolve to hold Britain, and, after the sack of Rome 410 CE by Alaric of the Visigoths, Rome began to marshal its resources closer to home. Emperor Valentinian I (r. 364-375 CE) had already decreased Roman military presence in Britain but in 410 CE, the emperor Honorius withdrew the Roman army from the island completely, telling the British administrators that they should now fend for themselves.

Anglo-Saxon Britain

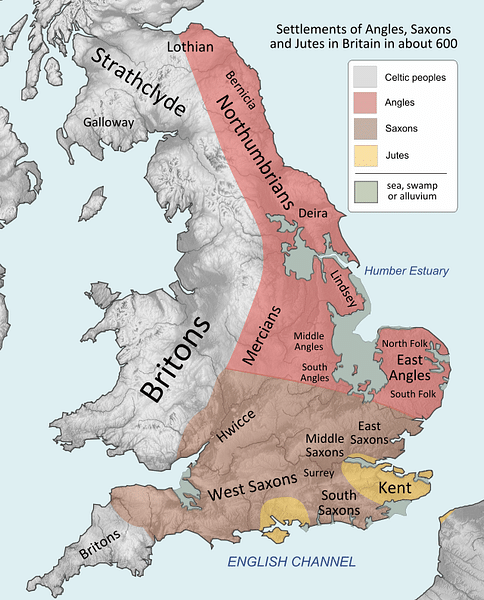

The void left by the Romans was filled by the migration of the Saxons who had established permanent settlements in Britain by 429. These people came to be referred to as Anglo-Saxons to differentiate from those who remained on the continent and were actually a diverse group of Saxons, Angles, and Jutes. Their appearance in Britain was characterized as a large-scale invasion by the historian Gildas (l. 500-570), and this narrative was continued by Bede (l. 672-735) and Nennius (l. 9th century) and then repeated by later historians.

According to the most famous version of this story (as told by Gildas), the Britons appealed to Rome for military assistance against invasions by the Picts, and when they were told no help was coming, they invited the Saxons – with their allies of the Angles and Jutes – to come as mercenaries. The Anglo-Saxon warriors dispensed with the Picts and then turned on their hosts, establishing themselves as overlords until they were defeated by the British champion Ambrosius Aurelianus at the Battle of Badon Hill c. 460. Bede and Nennius further embroidered this tale (with Nennius adding the detail of the war chief Arthur as the hero of Badon Hill, who would then be developed by others as King Arthur of the Britons), and this was regarded as authentic history for centuries.

Modern scholarship has rejected this version of events, however, and it has now been established that the Anglo-Saxons migrated to Britain peacefully and lived among the Britons. The invasion narrative may have been inspired by the raids of Saxon pirates who continued to prey on coastal towns even after the Anglo-Saxons had established themselves, most likely from an initial foothold at Kent. From Kent, the new arrivals spread in different directions, joining previously established communities and participating in trade, as well as founding their own settlements which came to be known as Essex (East Saxons), East Anglia, Sussex (South Saxons), Mercia (with Middlesex – Middle Saxons – emerging later as part of Essex), and Wessex (West Saxons).

Wessex was founded by the Saxon chief Cerdic who arrived in Britain in 495 with his son Cynric at the head of an expeditionary force and defeated the Welsh and Britons in battle. Although Cerdic is still referenced as a Saxon, modern scholarship suggests he may have been a British earl who had lost his kingdom, fled to the Saxons and learned their language, and then returned with a sizeable Saxon army to reclaim what had been taken from him. Who Cerdic was is still debated by scholars (some even claiming he was the basis for the figure of King Arthur) and the historical works of the period, including the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, are of little help as they either provide scanty information or narratives informed by legend. Scholar Roger Collins notes:

There is an unbridgeable chronological gulf between the supposed founding period of the notional Kingdom of Wessex in the late fifth century and the next period in which those who are said to be members of its ruling house appear, in the second half of the sixth century. Much of the information relating to the early phase is of a distinctly 'folkloric' or rationalizing character. (178)

Whoever he may have been, Cerdic's reputation as a great warrior-king was so impressive that later genealogies of the English monarchy claimed him as their ancestor, and only his descendants could legitimately claim kingship of Wessex up through and after the reign of Alfred the Great (871-899), the first Anglo-Saxon king to unite the land against the threat of the Viking raids in Britain. His grandson, Aethelstan (r. 927-939), became the first King of England which, by that time, had become more or less united under a central government and religion. Britain became Christianized beginning in 597, after the arrival of St. Augustine of Canterbury who converted the royal court at Kent. The Christian communities along the coast were the first to experience the sudden attacks of the Viking raiders.

Conclusion

Although Christianity played a major role in unifying the people culturally, the catalyst for political unity was the Viking raids which began in 793 striking first at the abbey of Lindisfarne. The Vikings chose religious centers on the coast initially because of their riches and the fact they were simply easy prey as the clergy were unarmed. In time, they would mount full-scale invasions, however, such as the arrival of the Great Army in 865 under Halfdane (c. 865-877) and Ivar the Boneless (c. 870) in East Anglia. From this base, they marched on other communities, defeating every army sent against them until they were defeated by Alfred the Great, who had marshalled an army against them, at the Battle of Eddington in 878.

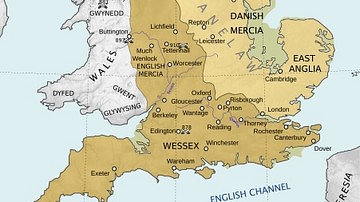

This victory led to the partitioning of Britain into the region of the Danelaw in East Mercia under Halfdane and the Kingdom of East Anglia under another Viking leader, Guthrum, with the Kingdom of Wessex under Alfred. Peace was uneasy, however, and in 1013, Britain was invaded by Sven Forkbeard (l. 986-1014) in retaliation for the massacre of Danes in British territory. After his death, his son Cnut the Great (l. 1016-1035) became king of Denmark and united it with Britain, then with Norway and Sweden, introducing diverse cultural influences to each of these regions through increased trade.

The last Viking king, Harald Hardrada (l. 1046-1066), invaded Britain in 1066 and so significantly weakened the Anglo-Saxons under their king Harold Godwinson that, when the Norman conquest of Britain was launched that same year, the Battle of Hastings was a decisive Norman victory. It is probable that the Normans under William the Conqueror would have won at Hastings anyway, but the Viking incursion under Hardrada almost assured it.

The Norman conquest exerted enormous influence on the development of the culture of Britain, setting the course for further expansion of the arts, language, literature, religion, military and civilian technologies, and architecture going forward. The Normans, like each of the peoples who arrived in Britain as immigrants or invaders introduced the varied influences which eventually resulted in the rich and diverse culture of Britain in the modern era.