Ptolemy XV Caesar “Theos Philopator Philometor” (“the Father-loving Mother-loving God”) (c. 47-30 BCE), better known by his unofficial nickname Caesarion or “Little Caesar” in Greek, was the oldest son of Cleopatra VII (69-30 BCE) and was the last Ptolemaic king of Egypt. Caesarion is usually assumed to have been the son of Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) who had an intermittent affair with Cleopatra from their meeting in 47 BCE until his death in 44 BCE.

Caesarion reigned as Cleopatra's co-ruler from 2 September 44 BCE to 12 August 30 BCE, when Cleopatra committed suicide. Although practically an exile, Caesarion was technically sole ruler of the Ptolemaic Kingdom until he was executed by Octavian (Caesar's grand-nephew, later Augustus Caesar, r. 27 BCE-14 CE) in late August 30 BCE.

Birth & Ancestry

Ptolemy Caesar XV was born to Cleopatra VII in the summer of 47 BCE. As a member of the Macedonian Ptolemaic dynasty, Caesarion was of predominantly Greek descent on his mother's side and had little, if any, Egyptian ancestry. An Egyptian stele from the Serapeum in Memphis is usually interpreted as recording his birthdate on June 23, 47 BCE, a few months after the Roman dictator Julius Caesar had departed from the country. Caesar had fought to restore Cleopatra to the throne in the Alexandrian War (September 48-January 47 BCE), and the two were having a famously scandalous affair which caused Caesar to linger in Egypt for a few months after the war was concluded.

Finally he [Caesar] called her [Cleopatra] to Rome and did not let her leave until he had ladened her with high honours and rich gifts, and he allowed her to give his name to the child which she bore. In fact, according to certain Greek writers, this child was very like Caesar in looks and carriage. (Suetonius, translated by Rolfe, 71)

The historian Nicolaus of Damascus (c. 64 BCE - c. early 1st century CE) stated that Julius Caesar actually went so far as to repudiate Caesarion in his will. However, this detail is not repeated in any other surviving accounts and is only mentioned in order to refute rumours that Julius Caesar aspired to be a king. Additionally, there would have been no need for Julius Caesar to legally distance himself from Caesarion given the latter's illegitimacy.

After the Ides of March (Julius Caesar's assassination on March 15, 44 BCE), the issue of Caesarion's paternity was raised by Caesar's friends and associates despite the fact that the status of Octavian as Caesar's heir was clear. The politically charged question remained open as supporters of Octavian actively denied that Caesar had fathered Caesarion, and detractors of Octavian actively promoted Caesarion as Caesar's son.

Mark Antony declared to the senate that Caesar had really acknowledged the boy, and that Caius Matius, Caius Oppius, and other friends of Caesar knew this. Of these Caius Oppius, as if admitting that the situation required apology and defence, published a book, to prove that the child whom Cleopatra fathered on Caesar was not his. (Suetonius, translated by Rolfe, 71)

Given the absence of evidence to the contrary, it is generally assumed that Caesarion was Julius Caesar's biological child. However, alternate theories have been put forth regarding Caesarion's paternity and the issue remains somewhat controversial. It has been suggested that Caesar was infertile as he only acknowledged one biological child in his entire life, despite three marriages and numerous extramarital affairs. Conversely, a low birth-rate was typical of the Roman aristocracy at this time and it is plausible that Caesar may have had illegitimate children that went unrecognized such as Junia Tertia. Furthermore, Cleopatra was not reputed to have had any lovers prior to meeting Caesar which precludes any alternate candidates for Caesarion's paternity.

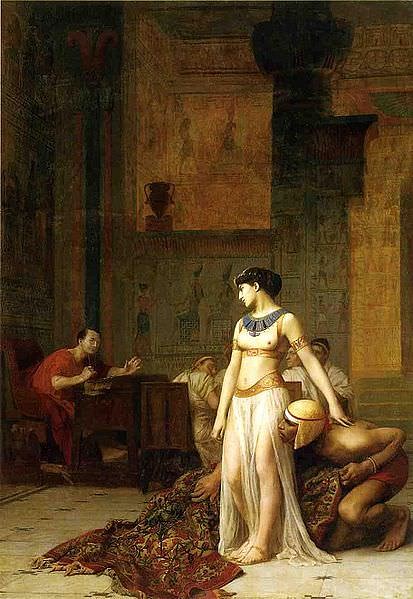

Caesarion & Cleopatra in Rome

Cleopatra visited Rome with her brother and nominal co-ruler Ptolemy XIV (c. 60/59-44 BCE) on at least two occasions. The Egyptian royal family is known to have visited Rome in 46 BCE and again in 44 BCE, residing in Julius Caesar's villa in the Horti Caesaris both times. During this time Caesar and Cleopatra maintained an affair which became the subject of scandal in Rome. Caesarion almost certainly accompanied his mother in 46 BCE although contemporary sources only take note of him in 44 BCE, following Caesar's assassination.

In 46 BCE, Caesar dedicated a temple in the Forum Julium to Venus Genetrix, the patron of maternity and marriage. Caesar was supposedly descended from Venus Genetrix through his mythological ancestor Aeneas, a demigod linked to the founding of Rome. Caesar made the controversial choice to unveil a gilded statue of Cleopatra as Isis-Venus within the temple during its dedication. The birth of Caesarion has been cited as a possible occasion to inspire the dedication of this politically charged artwork. A mosaic excavated from the House of Marcus Fabius Rufus in Pompeii is believed to depict this statue, seemingly portraying Cleopatra and Caesarion as the mother-son duo of Venus and Cupid. The placement of this statue in the Temple of Venus Genetrix drew a connection between Caesar's supposed heritage as the descendant of Venus and Cleopatra's alleged status as the reincarnation of Isis-Venus.

Julius Caesar was assassinated by a group of senatorial conspirators on March 15, 44 BCE. Cleopatra remained in Rome long enough for Caesar's will to be read. To her disappointment, Caesarion was not acknowledged by Caesar. According to this will, Caesar posthumously adopted his grand-nephew Octavian (the future Augustus). Cleopatra fled Rome within a month of Caesar's assassination, taking with her the two-year-old Caesarion. This would be Caesarion's last visit to Rome as he never returned to the to him unwelcome city in later life.

Education & Upbringing

Caesarion was raised in Alexandria, Egypt, the capital of Hellenistic culture at the time, and had few Egyptian or Roman influences in his upbringing. Most of Caesarion's childhood was quite secure due to the relative stability of his mother's reign. In spite of his illegitimacy, Caesarion's role as Cleopatra's successor seems to have gone unchallenged in Egypt.

Like most princes of the Ptolemaic Dynasty, Caesarion would have been trained in the arts of rhetoric, oration, politics and philosophy. Caesarion's personal tutor during his adolescence was a Greek scholar named Rhodon. Little is known of Rhodon's career, a sharp contrast to the illustrious careers of Philostratus, Cleopatra's childhood tutor, and Nicolaus of Damascus who tutored Caesarion's siblings before becoming one of the most influential historians of the 1st century BCE. Caesarion's own mother was yet another influence on his intellectual development and that of his siblings. A skilled politician and orator, Cleopatra was credited with speaking eight languages and authoring works on topics such as medicine and pharmacology.

King of Egypt

The death of Julius Caesar left Cleopatra in a weakened political position as she lost her strongest ally in Rome. However, Cleopatra was able to carefully maintain a conciliatory relationship with both the Liberators (led by the assassins of Caesar) and the Second Triumvirate, the two main factions which had emerged in the aftermath of Caesar's assassination. By the summer of 43 BCE, Cleopatra had begun to throw her lot in with the Second Triumvirate, and particularly with the leading triumvirs Marc Antony and Octavian. The alliance between Cleopatra and the Second Triumvirate was key to her agenda of spreading her sphere of influence over the former extent of the Ptolemaic Empire, as it was only with the support of Antony and Octavian that she was able to establish control over territories like Cyrene and Phoenicia.

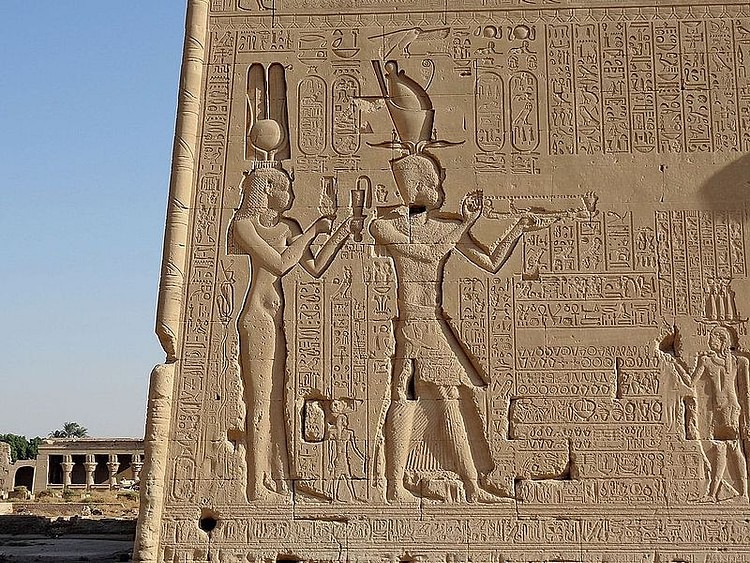

Ptolemy XIV died suddenly in 44 BCE, and it was rumoured that Cleopatra had poisoned her adolescent brother to remove any threat to her rule. Shortly after Ptolemy XIV's death, Caesarion was proclaimed king and became Cleopatra's new co-ruler. This succession was officially recognized by the Roman Senate in early 43 BCE, ensuring the legitimacy of Caesarion's official reign. Artistic representations of Cleopatra and Caesarion deliberately paralleled the relationship between the Egyptian goddess Isis and her son Horus. In Egyptian mythology, Isis was the maternal protector of her son Horus who became the rightful king of Egypt after the violent assassination of Horus' father Osiris.

Caesarion's alleged status as Julius Caesar's son brought Cleopatra into conflict with Caesar's adopted son and heir Octavian (63 BCE - 14 CE). Partly as a result of this rivalry, Cleopatra chose to ally with Octavian's rival Mark Antony (83–30 BCE) who had taken control of Rome's eastern provinces after Caesar's death. To this end, Cleopatra met with Antony in Tarsus in 41 BCE and invited the triumvir to visit her in Alexandria during the winter of 41 BCE. Antony left Egypt before the end of the year of 40 BCE and strengthened his alliance to Octavian by marrying his newly widowed sister Octavia. Antony had two daughters with Octavia, but he maintained contact with Cleopatra.

At the age of ten, Caesarion accompanied Cleopatra on a journey to Antioch where they met with Antony in late 37 BCE. With the consent of Octavian, Antony granted additional territories in Cyrene, Cilicia, Crete and the Levant to the Ptolemaic Kingdom. Antony and Cleopatra were married sometime between 37 BCE and 34 BCE, a situation that caused a scandal as the Roman triumvir remained married to Octavia until 32 BCE. Cleopatra had a total of three children with Mark Antony, including the twins Alexander Helios (40 - c. late 1st century BCE) and Cleopatra Selene (40-6 BCE), and Ptolemy Philadelphus (36 - c. late 1st century BCE).

King of Kings & the Donations of Alexandria

In 34 BCE, an elaborate coronation ceremony known as the Donations of Alexandria was performed in the Egyptian capital. With carefully staged pomp, Mark Antony celebrated a Roman triumph following his campaigns in the East and bestowed further territories on the Ptolemies. However, the tremendous ceremonial significance of the proceedings exceeded the actual transfer of territory which occurred. Out of the territory "donated" to the Ptolemaic Kingdom, most were either already under Ptolemaic rule or under the control of Rome's rival, the Parthian Empire.

Antony's cession of Libya, Egypt, Coile Syria, Phoenicia, Cilicia, and Cyprus to Cleopatra was purely symbolic as she already ruled these territories. Media and Parthia were firmly under Parthian control and Antony's bestowal of these territories was hypothetical at best, to be secured after some future conquest. This leaves the provinces of Syria, Asia and Bithynia as the only territories ceded in the Donations of Alexandria which had actually been under Roman rule. The Kingdom of Armenia can also be added to the list of Roman territory ceded to the Ptolemaic Kingdom as Antony had conquered the kingdom earlier that year, and the Donations of Alexandria doubled as a triumphal celebration of the conquest.

Caesarion, now 14 years of age, was elevated above all his siblings and declared King of Kings while his mother was named Queen of Kings. In addition to this, Antony declared Caesarion to be Julius Caesar's true son, an act which earned the ire of Octavian who was keen to reserve that title for himself. Antony formally granted Cleopatra and Caesarion dominion over an empire theoretically stretching from India to the Hellespont. Within this empire, Cleopatra's children by Mark Antony were granted their own dominions. Alexander Helios was declared king of Armenia, Media and Parthia, though the latter two kingdoms were still unconquered by Antony. Cleopatra Selene was declared queen of Cyrene, and Ptolemy Philadelphus was declared king of Phoenicia, Syria and Cilicia.

Caesarion may have been his mother's equal in name, but at least until he came of age he was still subject both to her and to Mark Antony. At the Donations, Caesarion's throne was lower than his mother's while Mark Antony, who held no royal titles, sat on an equal level with the queen. This balance of power had already been hinted at by the portrayal of Antony on coins minted by Cleopatra in the East and in Antony's role as Dionysius, consort to Cleopatra's Isis during the ceremony.

The Donations themselves were not so much a relinquishment of Roman hegemony in the East to Ptolemaic rule, but an attempt to reconcile Roman authority with the monarchical traditions of the Near East and Northeast Africa. By propping up Cleopatra's claim to the former empires of her Ptolemaic and Seleucid ancestors, Antony had intended to reinforce Roman influence over the East and weaken Parthian claims over the region. Despite the lack of significant change to the status quo following the Donations of Alexandria, the grandiose titulature and far-reaching claims of Cleopatra and Antony inadvertently ensured a harsh reaction to this event in Rome.

The Donations of Alexandria launched an intense propaganda war between Antony and Cleopatra in the East, and Octavian in Italy. Caesarion's claims as Julius Caesar's biological son were raised by Antony, prompting Octavian's supporters to deny his paternity and accuse Antony of becoming corrupted by Eastern ways. In 32 BCE, Antony formally divorced Octavia (Octavian's sister, married to Mark Antony since 40 BCE), effectively severing the last thread of his alliance with Octavian. That same year, Octavian illegally seized Antony's will from the Temple of Vesta. Octavian revealed the contents of this will which confirmed Caesarion as Caesar's son, acknowledged his children by Cleopatra and most scandalously, declared his intentions to be buried with Cleopatra in Egypt. Octavian further accused Cleopatra of corrupting and manipulating Mark Antony with an agenda to rule as queen over the Roman Republic.

The Roman Senate declared war on Cleopatra in the spring of 32 BCE, citing Cleopatra's increasing influence over Antony and her anti-Roman agenda. In truth, this declaration of war was the result of political tensions between Antony and Octavian who had both vied for the position of Caesar's successor for more than a decade. At the decisive Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, Antony and Cleopatra's naval forces were defeated by the forces of Octavian and his admiral Agrippa. Antony and Cleopatra then fled to Alexandria where they began preparing to carry on their doomed war with Octavian.

Caesarion came of age in the summer of 30 BCE, at which point he was enrolled in the lists of the gymnasium. Far from a mere athletic facility, the gymnasia of the Hellenistic world were important centres of social life where intellectual and physical talents were trained. In the Greek communities of Ptolemaic Egypt, enrolment in the gymnasium signified a young man's entry into life as an adult citizen. Most youths were enrolled in the gymnasium at the age of 14 but exceptions were sometimes made for princes like Caesarion - who was 17 at this time - given their unique life circumstances.

“[Antony] turned the city to the enjoyment of suppers and drinking-bouts and distributions of gifts, inscribing in the list of ephebi the son of Cleopatra and Caesar, and bestowing upon Antyllus the son of Fulvia the toga virilis without purple hem, in celebration of which, for many days, banquets and revels and feastings occupied Alexandria.” (Plutarch's Life of Antony, translated by Perrin, 301)

This enrolment was a landmark moment in the life of Caesarion as he entered manhood in the eyes of his peers, a time when many rulers began to truly step into their political role. As these joyous events were unfolding, Antony and Cleopatra's efforts to carry on the war with Octavian were becoming increasingly hopeless. In an effort to maintain morale, the worst news was deliberately withheld from the Alexandrians while the city was kept in a festive mood.

Death & the Conquest of Egypt

In August of 30 BCE, Octavian invaded Egypt and was engaged by Antony in multiple futile battles. Fearing that Octavian would remove his last rival by having Caesarion killed, Cleopatra made plans to send her first-born away with a large amount of wealth. Caesarion was sent to the Dodekaschoinos in Ptolemaic Nubia where he would be able to depart from one of the Red Sea port cities which conducted trade with Arabia and the Indian subcontinent. Hellenistic contact with the East had been well established for centuries and Caesarion would have been able to live comfortably there, far from the reach of Octavian.

On August 1, 30 BCE, Antony fell on his sword, on the same day that Octavian captured the city of Alexandria. Cleopatra committed suicide on August 12, 30 BCE to avoid being paraded through Rome in Octavian's triumph. Shortly afterwards, Octavian invited Caesarion to return and rule Egypt as a client-king in his mother's stead. Rhodon advised Caesarion to return to Egypt and accept the crown that Octavian offered. It is unknown whether Caesarion's tutor betrayed him or earnestly believed that Octavian's offer was genuine. Arieus Didymus, a former patron of the Alexandrian court who had joined Octavian's cause, is credited with convincing the Roman conqueror that Caesarion was too great of a potential threat to live. To this end, Plutarch reports that Arieus told Octavian “Not a good thing were a Caesar too many” (translated by Perrin, 321).

Rather than being welcomed into the country with open arms, Caesarion was intercepted on the road and slain by Roman soldiers. His death ensured that Octavian would have no rival, either as ruler of Egypt or the perceived heir of Julius Caesar.

Egyptian chronologies record the brief reign of Caesarion after the death of Cleopatra but this was really a bureaucratic fiction which bridged the gap between Cleopatra and Roman Egypt. Instead of the lofty legacy his mother intended, Caesarion would be remembered by historians as the last Pharaoh of Egypt and one whose untimely death heralded the end of the Ptolemaic Kingdom.