Croesus (r. 560-546 BCE) was the King of Lydia, a region in western Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey) and was so wealthy that the expression "as rich as Croesus" originates in reference to him. Best known for his wealth, he is also famous for misinterpreting the message from the Oracle at Delphi, leading to his downfall.

His wealth, it is said, came from the sands of the River Pactolus in which the legendary King Midas washed his hands to rid himself of the Midas Touch (which turned everything he touched into gold) and in so doing, the legend says, made the sands of the river rich with gold. The Lydians, during the reign of Croesus’ father Alyattes (r.c. 635-585 BCE), were the first people to mint coins in the world (the Lydian stater, initially made of electrum) while Croesus later minted coins of gold and also funded construction of the great Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world, further associating him with money and seemingly unlimited wealth.

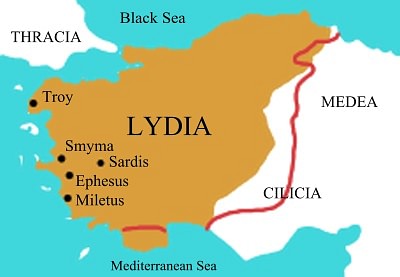

After conquering the cities of Aeolis, Doris, and Ionia, Croesus would not have needed a magical gold river to enrich himself as he received tribute from all of them as well as from Phrygia. Much of the information on his reign comes from the historian Herodotus (l. c. 484-425/413 BCE) who claims he consulted with the sage Solon (l. c. 640 - c. 560 BCE) who warned him against the sin of pride in thinking too highly of himself, advice he ignored, and that his fall was due to a misinterpretation of the message from the Oracle at Delphi concerning making war against the Persian Achaemenid Empire. He is also said to have had the Pre-Socratic Philosopher Thales of Miletus (l. c. 585 BCE) as an engineer in his army who helped divert the Halys River during the military campaign against the Persians, though his association with the philosopher seems to have done Croesus no more good than his consultation with Solon.

Although some historians have claimed that Croesus was largely a legendary figure, his signature at the base of one of the columns of the Temple of Artemis (now on display at the British Museum) is evidence that he was an actual historical king who ruled from the city of Sardis. He is frequently referenced in the present day in regard to vast wealth but his story also serves as a cautionary tale (as it did in antiquity) regarding pride and the risks inherent in the interpretation of signs, omens, and messages from the Divine.

Ancestry & Rise to Power

Croesus (pronounced KREE-sus) was the last king of Mermnad Dynasty (c. 700-546 BCE) which began with King Gyges (r. c. 680-645 BCE) who took the throne after assassinating King Candaules (last of the Heracliade Dynasty) at the request of Candaules’ wife. Gyges had been Candalules’ bodyguard and close confidant and the king, wanting confirmation that his wife was the most beautiful woman in the world, had Gyges hide behind their bedroom door to watch her disrobe. The queen noticed Gyges slipping out the door after watching her and, shamed at having been seen naked, offered him the choice of either killing her husband for orchestrating the plot or being killed himself; so Gyges killed Candaules, took his wife, and became king of Lydia.

Plato, in his Republic, Book II, 359d-360c, gives a more colorful version than the above from Herodotus in his tale of the Ring of Gyges where Gyges, a humble shepherd, finds a magic ring that makes him invisible and uses it to assassinate Candaules and take the throne of Lydia. However he came to power, the people were far from happy that he had unseated the Heracliade monarch as the dynasty claimed legitimacy from the great hero Heracles (Hercules) and so Gyges sent to the Oracle at Delphi to ask whether he should be king. The Oracle replied that he should and that his dynasty would last five generations before vengeance was demanded for Candaules' murder. Gyges ignored that last part, mobilized his army, and then conquered Miletus and Colophon before dying in battle fighting off Cimmerian raiders.

He was succeeded by his son Ardys (r. 644-637 BCE) who spent most of his reign battling the Cimmerians and was also most likely killed in battle. His son and successor, Sadyattes (r. 637-c. 635 BCE), was also probably killed by Cimmerian raiders. Sadyattes was succeeded by his son Alyattes who, allied with the Scythians, defeated the Cimmerians and stabilized his kingdom. He was the first king in history to issue coins and these were made from electrum (a mixture of gold, silver, copper, and other metals). He continued his father’s policy of aggression against the city-states of Ionia and lavish gifts given to the Oracle at Delphi in hopes of the god’s blessings. He died in 585 BCE after a battle with the Medes and Croesus became the fourth – and final – king of the Mermnad Dynasty.

After a struggle for power with his stepbrother Pantaleon, King Croesus continued the same aggressive policies toward the Ionian Greeks as his predecessors. Herodotus writes:

The Ephesians were the first Greeks Croesus attacked, but afterwards he attacked all the Ionian and Aeolian cities one by one. He always gave different reasons for doing so; against some he was able to come up with more serious charges by accusing them of more serious matters, but in other cases he even brought trivial charges. (I.26)

Having subdued Ionia, he then set his sights on the outlying islands of the Aegean and began building a navy to subdue them but, warned by a counselor that this was the very course the islanders hoped for – to defeat Lydia by sea – he abandoned his plans and forged treaties with the islands instead.

Reign

With the assistance of his new allies, Croesus then continued his policy of conquest. According to Herodotus:

After a while, almost all the people living west of the Halys River had been subdued. Except for the Cilicians and the Lycians, Croesus had overpowered and made all the rest his subjects – the Lydians, Phrygians, Mysians, Mariandynians, Chalybes, Paphlagonians, the Thynian and Bithynian Thracians, the Carians, Ionians, Dorians, Aeolians, and Pamphylians. (I. 28)

Croesus had learned administrative and political – as well as military – skills as a young man when his father had appointed him governor of Adramyttium, and he put these to use once he was king of Lydia. Recognizing the importance of alliances, he made peace with the Medes, honoring the marriage arranged by his father of his sister, Aryenis, to the Median king Astyages (r. 585-550 BCE). He also maintained trade relations with Egypt and the Neo-Babylonian Empire, further enriching his kingdom and himself.

Croesus standardized the monetary system of Lydia by issuing the first gold coins, improving on the coinage of his father. Scholar Jean Hatzfeld comments:

The half-Hellenized kingdom of Lydia first coined electrum since this natural alloy of gold and silver was obtainable from certain alluvial deposits, notably the sands of the river Pactolus. Later, the minting of silver coins of warranted value spread in Greece itself, where the metal was not too scarce. Finally, the Lydian King Croesus was the first to issue gold coins. At the same time and progressively, minting became a state prerogative. The governments of the Greek cities took away the right of coinage from private individuals and eventually reserved this valuable privilege for themselves. (44)

Croesus was now the most powerful monarch in Asia Minor, having expanded his territory all the way to the coast and from Pergamon in the north down the coast to the south. According to Herodotus, he considered himself the happiest man in the world but that would soon change through personal misfortune and the rise of Cyrus II (also known as Cyrus the Great, r. c. 550-530 BCE) who overthrew his grandfather, Astyages of Media, to establish the Achaemenid Empire.

Croesus’ Fall

Although Croesus’ troubles are mentioned by the writers Xenophon (l. 430 - c. 354 BCE) and Ctesias (l. 5th century BCE), among others, the two most famous stories regarding his fall come from the Histories of Herodotus (1.29-46 and 1.85-91). The first has to do with the great Athenian sage and lawgiver Solon the Wise. Solon travelled throughout Egypt and Asia Minor (also known as Anatolia) and came, at last, to the palace of Croesus at Sardis. Croesus was overjoyed to have so illustrious a visitor and was anxious to show off his treasuries and, after Solon had inspected them, asked him who, of all the men he had met in his travels, he would call the happiest.

Solon answered, “Tellus of Athens.” Croesus, upset that he himself had not been named, asked why Tellus. Solon answered that Tellus had lived well and happily, had a beautiful family, and had died gloriously for Athens in battle. Croesus, conceding this was a good life, and hoping he would at least be named second, then asked Solon who else he would consider the happiest of men. Solon answered:

"The brothers Cleobis and Bito of the Argive race” and explained why, noting again a life well lived and a good death. Croesus, angered now, shouted: "Man of Athens, am I not the happiest man in the world? Dost thou count my happiness as nothing?" Solon replied calmly:

In truth, I count no man happy until his death, for no man can know what the gods may have in store for him. He who unites the greatest number of advantages, and retaining them to the day of his death, then dies peaceably, that man alone, sire, is in my judgment entitled to bear the name of 'happy.' But in every matter, it behooves us to mark well the end: for oftentimes the gods give men a gleam of happiness, and then plunges them into ruin. (Herodotus, I.32)

Croesus sent Solon away, thinking his reputation for wisdom overrated, but he would soon learn the truth of what Solon had said through the events narrated by Herodotus' second story. The first misfortune to come upon Croesus was the death of his son Atys, killed while hunting a boar in Olympus (and, ironically, killed by the man whom Croesus had sent on the hunt for the express purpose of keeping Atys safe). Croesus grieved for his son for two years until he was alerted that the Persians under Cyrus were gaining power and decided he should check their progress sooner rather than later.

He sent to the Oracle at Delphi to know whether he should go to war against the powerful Persian Empire Cyrus had managed to establish so quickly and the oracle replied: "If Croesus goes to war he will destroy a great kingdom." Pleased by this answer, Croesus made his necessary alliances and preparations and went out to meet the Persian army at the Halys River. Herodotus notes how this is when Thales of Miletus, an engineer in Croesus’ corps, made the army’s passage across the river possible:

When he came to the Halys River, Croesus then, as I say, put his army across by the existing bridges; but according to the common account of the Greeks, Thales the Milesian transferred the army for him. For it is said that Croesus was at a loss how his army should cross the river since these bridges did not yet exist at this period; and that Thales, who was present in the army, made the river, which flowed on the left hand of the army, flow on the right hand also. He did so in this way: beginning upstream of the army, he dug a channel, giving it a crescent shape, so that it should flow round the back of where the army was encamped, being diverted in this way from its old course by the channel, and passing the camp should flow into its old course once more. The result was that, as soon as the river was divided, it became fordable in both its parts. (I.75)

The Battle of Pteria (c. 547 BCE) was a draw and Croesus retreated back to Sardis where the army began demobilizing for the winter. Croesus expected Cyrus to do the same, as this was customary, but Cyrus instead followed and pressed the attack. He defeated Croesus at the Battle of Thymbra (late 547 BCE) after neutralizing Croesus' cavalry by mounting his own cavalry on camels (whose scent frightened the Lydian horses) and, after a 14-day siege, captured Sardis and its king. After the fall of Sardis, Croesus' wife committed suicide and Croesus was dragged before Cyrus in chains.

For daring to raise an army against the Persian Empire, Cyrus ordered Croesus to be burned alive along with 14 noble Lydian youths. When Croesus saw the flames of the pyre lapping toward him, he called out for Apollo to rescue him and, according to Herodotus, a sudden rain shower broke overhead and put out the fire. Croesus was saved from burning to death but was still the captive of the Persian King and, remembering the words of Solon the Wise, cried out, "O Solon! Solon! Solon!" Cyrus asked a translator what this word meant, and Croesus told the story of Solon's visit, how no man can be counted happy until after his death, and further, of how he was misled by the Oracle at Delphi who had told him that if he went to war against Cyrus, a great kingdom would fall, and here the “great kingdom” destroyed had been his own.

Cyrus was so moved by this story that he ordered Croesus to be released and had him send to Delphi for an answer from the god as to why he was betrayed. The answer came back that the Oracle had spoken only truth - a great kingdom had, in fact, been destroyed by Croesus – and it was not the fault of the gods if humans misinterpreted divine messages. If Croesus had not been so confident in his own wisdom, the Oracle said, he would have asked a second question as to whether it would be Cyrus’ kingdom or his own that would fall.

Conclusion

Herodotus further relates, in the response of the Oracle, that the fall of Croesus was due to the sin of Gyges in assassinating Candaules at the request of the queen and usurping power from the Heracliade Dynasty to establish his own:

Not even a god can escape his ordained fate. Croesus has paid for the crime of his ancestor four generations ago, who, though a member of the personal guard of the Heracliade, gave in to a woman’s guile, killed his master, and assumed a station which was not rightfully his at all. In fact, [the gods] wanted the fall of Sardis to happen in the time of Croesus’ sons rather than Croesus himself, but it was not possible to divert the Fates. (I. 91)

Croesus, upon hearing the Oracle’s response, recognized he and his ancestor had brought about his misfortune and placed himself at Cyrus’ mercy. Cyrus felt sorry for Croesus and, according to Herodotus, kept him on as a wise counsellor. This positive account of Croesus' end has been disputed by many scholars, both ancient and modern, as well as other tales in which the god Apollo carried Croesus and his family away after the fall of Sardis and they all lived happily ever after.

There is no record of Croesus’ death and so later writers seem to have felt free to provide a positive conclusion to his life story. Most modern-day scholars and historians believe that Croesus died on the pyre (or took his own life) but that the people did not care for that ending to the story of so wealthy and powerful a king. Still, the story of Croesus’ fall served as a cautionary tale among the Greeks on hubris and a warning on not tempting the gods' wrath by thinking of oneself as the happiest person in the world.