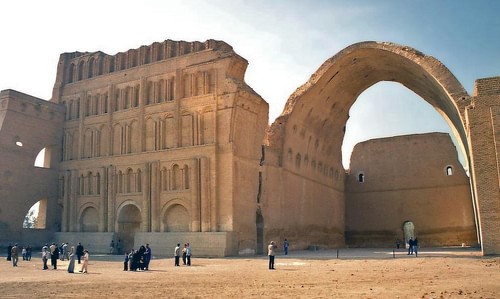

Ctesiphon was an ancient city and trade center on the east bank of the Tigris River founded during the reign of Mithridates I (the Great, 171-132 BCE). It is best known in the modern day for the single-span arch, Taq Kasra, which is the most impressive aspect of the city's ruins.

It was the capital of the Parthian Empire (247 BCE - 224 CE) before being destroyed by Rome and was then restored to become capital again of the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE). The Sassanian king Ardashir I (r. 224-240 CE) rebuilt the city and was crowned there, as his successors would be also.

The city became an important center for trade along the Silk Road. Caravans would stop at Ctesiphon with goods from China and these goods ferried across the Tigris to the city of Seleucia (founded during the Seleucid Empire, 312-63 BCE) to be traded and then go on from there further. Ctesiphon thus became known as the terminus for one of the many branches of the Silk Road.

It was conquered by the Romans three times and was the site of the Battle of Ctesiphon between Ardashir I and Alexander Severus of Rome (r. 222-235 CE) in 233 CE. The city was added to by Ardashir I's successors and remained an important cultural and economic center until it fell to the invasion of the Muslim Arabs in 637 CE who looted it. Afterwards, bricks and other materials from Ctesiphon were used to build the city of Baghdad. The ruins of Ctesiphon are presently in a state of slow deterioration in the village of Salman Pak, Iraq, a suburb of Baghdad.

Founding & Parthian Empire

The city was known as Tisfun to the Persians, Ktesiphon to the Greeks, and is best known by its Latin designation, Ctesiphon; the meaning of the name is unknown. It was founded on the eastern bank of the Tigris River, across from the city of Seleucia, as a military camp, possibly (according to Strabo's Geography 16.1.16), because the Parthian army did not wish to be garrisoned in Seleucia and have to mix with the Greek residents there. Pliny (l. 23-79 CE), however, claims the city was purposefully founded to be grander than Seleucia and attract that city's inhabitants across the river to the new site, thus making Seleucia obsolete (Natural History VI.122). It is possible there was some community there prior to this time – possibly a small trading village – which would have attracted Mithridates I's attention to the location or it could have simply been chosen for its proximity to Seleucia, if one accepts Pliny's claim for its founding.

The much earlier Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE) fell to the armies of Alexander the Great in 330 BCE, and Alexander's general Seleucus I Nicator (r. 305-281 BCE) took control of the region after Alexander's death in 323 BCE. Seleucus I ruled the western part of his empire from Antioch (on the Orontes River) and established the city of Seleucia for his son, Antiochus I Soter (co-rule 291-281, r. 281-261 BCE), to rule over the eastern regions.

No expense, therefore, was spared on Seleucia, and it is possible – if not probable – that Pliny is correct that Mithridates I would have wanted a Parthian city established nearby which would outshine the Greek's work and encourage people to abandon the old city for his new and much grander vision at Ctesiphon. The Seleucid Empire had been declining for years – and had lost most of its territory to Rome - before it finally fell to the Parthians, and it makes sense that a Parthian king would have wanted to show the might of his empire through a new city that overshadowed Seleucid efforts.

The city developed into a major political and trade center by the reign of the Parthian king Godarz I (91-80 BCE) and was made the capital of Parthia under Orodes II (r. 58-57 BCE). The city was refurbished and expanded upon during the reign of Vologases I (51-80 CE) who further encouraged trade, making Ctesiphon one of the most important trade centers in the region. There is little else known of Parthian Ctesiphon because of the lack of records which were destroyed, along with the city, by an invading Roman army.

The city was taken by the Roman emperor Trajan c. 115 CE shortly before he burned Seleucia (which was later destroyed by Avidius Cassius in 165 CE after he had conquered Ctesiphon in 164 CE). Roman advances against the city continued under Septimus Severus who sacked the city in 197 CE and sold the inhabitants into slavery as a show of force. Ctesiphon was more or less deserted afterwards and, as the Parthian Empire was crumbling, no effort was made to rebuild or repopulate the city.

Sassanian Empire & the Battle of Ctesiphon

Ardashir I had been a general in the Parthian army who led the revolt which toppled the empire. He then founded the Sassanian Empire and began a series of building projects which included the restoration of the city which he made his capital. From Ctesiphon, Ardashir I issued his famous ultimatum to Rome demanding that all the territories which had once belonged to the Achaemenid Empire which were now in Rome's possession be returned to him, their rightful owner.

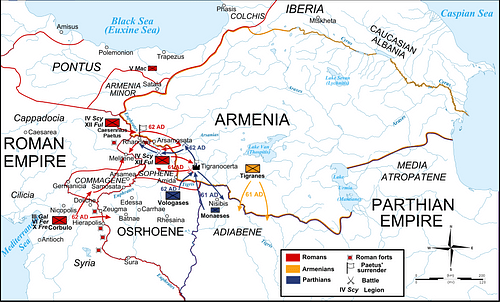

Ardashir I did not wait for an answer but marched into Mesopotamia along with his son Shapur I (r. 240-270 CE), took back Syria, and drove the Romans from the region in 229 CE. Alexander Severus demanded he withdraw and, in answer, Ardashir I took Cappadocia. Severus responded by arresting 400 delegates Ardashir I had sent to Rome and sentencing them to slave labor on farms before then launching a three-pronged assault on the Sassanians in 231 CE.

The first army came toward Ctesiphon from the north, the second from the south, and the third in a straight line between these two. The three armies encountered resistance but none they took very seriously, unaware that the main part of the Sassanian forces – including the famous heavily-armed cavalry of the Savaran Knights – was waiting for them.

The three-pronged attack seemed good in theory but, in practice, all Ardashir I had to do was monitor each advance, send a strike force where he felt it would do the most damage while not seriously alarming the Romans, and then continue this strategy until the Roman forces were fooled into thinking the Sassanians were no real threat. This is precisely what he did do so that, by the time the Romans reached Ctesiphon, they were unprepared for the size of the force arrayed against them or the tactics then used. Scholar Kaveh Farrokh cites the historian Herodian's description of the battle:

The Persian king attacked the [Roman] army with his entire force [of heavily armored cavalry and horse archers], catching them by surprise and surrounding them in a trap. Under fire from all sides, the Roman soldiers were destroyed…in the end they were all driven into a mass…bombarded from every direction…the Persians trapped the Romans like fish in a net; firing their arrows from all sides at the encircled soldiers, the Persians massacred the whole army…they were all destroyed…this terrible disaster, which no one cares to recall, was a set-back for the Romans, since a vast army had been destroyed. (185)

Severus, obviously, was least inclined to recall the defeat and so rewrote the event in his victory speech to the Roman Senate in September 233 CE claiming he had completely defeated the Sassanian king and “had destroyed 218 elephants, 1,800 scythed chariots, and 120,000 of their [Sassanian] cavalry” (Farrokh, 186). Farrokh – and many scholars before him – have noted the inflated numbers Severus cites which could not possibly be accurate but his entire “victory speech” was a fabrication so exaggerated numbers should hardly come as a surprise.

After the battle, Ardashir I retired from Persian warfare and encouraged his son to assume greater responsibility and control. At some point, whether before the battle or after, Ardashir I initiated the policy of bringing Zoroastrian priests to the capital to recite the verses of the Avesta (scripture of Zoroastrianism) and have them written down. This practice would continue under Shapur I but only be completed under Shapur II (r. 309-379 CE) and Kosrau I (r. 531-579 CE). Ctesiphon, therefore, was instrumental in the preservation and development of Zoroastrian theology. Although there was a fire temple (Zoroastrian place of worship) in the city, it was not one of the Great Fires of Zoroastrian worship which people would make pilgrimage to.

Further Developments & Taq Kasra

The city flourished under Shapur I to become a major cultural center and the heart of the Sassanian Empire. The decree for the founding of the Academy of Gundeshapur, the leading intellectual center of the region and the first teaching hospital, would have been issued from Ctesiphon. Building projects and plans initiated by Ardashir I, and greatly expanded under Shapur I and his successors, enlarged the city in every direction creating lesser cities and suburbs in the surrounding area and even along the opposite shore of the Tigris.

Ardashir I had set the model for this expansion with his city of Weh-Ardashir (called New Seleucia by the Greeks) where he built his palace and introduced elements of ancient Persian art and architecture such as the minaret and dome. Later Sassanian monarchs would follow suit with elaborate buildings ornamented with decorative friezes, marble floors, mosaics, and courtyards surrounding lush gardens. Farrokh comments:

The city merged with Seleucia and other nearby settlements into one vast, sprawling, urban metropolis, which the Arabs called al-Mada'in (literally, “the cities”). Many of the architectural styles and arts of “Greater Ctesiphon” influenced (and were influenced by) the Byzantine west. After its fall to the Arabs in the 7th century CE, Ctesiphon was to exert a powerful legacy on the arts and architecture of the Islamic world. (125)

Among the most impressive structures in the city was the great arch known as Taq Kasra (or the Arch of Ctesiphon) built either by Shapur I or Kosrau I. Taq Kasra is the largest single-span vaulted arch of unreinforced brickwork in the world, even in the present day, and was constructed as the entrance to the imperial palace and throne room. In this, as in all aspects of Sassanian architecture, the builders drew on the models of the Achaemenid and Parthian empires but also borrowed liberally from Roman engineering, design, and technique.

A defining characteristic of Sassanian culture – whether in architecture or anything else – is their talent for drawing on the past, and others' achievements in a given area, and improving upon them. Taq Kasra is among the best examples of this practice as it was unequaled by any other culture at the time and remains so.

The imperial palace the archway led to was the home of the king but, surrounding it, were the administrative offices. The Sassanian routinely modeled their empire on that of the Achaemenids and centralized the Persian government at Ctesiphon. In keeping with Achaemenid practice, however (and simply as a matter of pragmatism), they used Ctesiphon only as their winter residence, moving to summer quarters in the highlands in warmer months. The government continued to operate from Ctesiphon at these times, however, as described by the scholar Homa Katouzian:

The administration of the state was centralized along Achaemenid lines. A few vassal states remained, the remaining provinces being run not by satraps but by governors-general or marzbans, who played an important role, especially in the frontier provinces, in keeping the peace and managing their regions. Secretaries, administrators, or scribes made up the heads of the bureaucracy [at Ctesiphon] and ran the divans, or ministries, including matters regarding finance, justice, and war. (47)

From Ctesiphon, these bureaucratic administrators would levy and collect taxes, issue calls for conscription, and otherwise maintain the Sassanian Empire. They also regulated trade and, as noted, Ctesiphon became a terminus for goods coming from China and heading to the west, growing increasingly wealthy from trade. Ctesiphon would continue as the greatest and most important city of the empire until its fall to the Muslim Arabs in the 7th century CE.

Fall of Ctesiphon

Although Roman forces approached or even attacked the city at various times during the Sassanian Period, it held against any attempts to take it until the Muslim Arab invasion of 636/637 CE. The Arabs had been making incursions into Persian lands prior to the reign of the last Sassanian king, Yazdegerd III (632-651 CE) and he intended to stop them. He sent his general Rostam Farrokhzad (d. 636 CE) against them, commanding a large force, and he met them outside the small town of al-Qadisiyyah in 636 CE.

Rostam demanded their surrender but the response came back that the Sassanians had only two choices: to submit to the Arab Muslims and become their slaves or die by the sword; Farrokhzad chose battle-to-the-death. The Battle of al-Qadisiyya (636 CE) began with a Sassanian advance. Rostam's forces outnumbered the Arab armies but the Arabs' superior tactics, and their use of camels in cavalry units which were more effective on sandy terrain, broke the Sassanian lines. Rostam was killed and his army scattered.

Afterwards, the Arab commander, Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas (l. 595-674 CE), advanced his forces on the metropolis of Ctesiphon. The surrounding cities surrendered and made peace while the people of Ctesiphon, including the noble family, bureaucrats, and garrison, abandoned the city and fled. When the Arabs arrived, the city was empty, and they looted it without opposition, emptying the treasury and taking what valuables could be carried. The imperial palace was afterwards turned into a mosque for a time but, with the rise of nearby Baghdad – built largely from materials taken from Ctesiphon – the city was deserted and fell into ruin.

Conclusion

Ctesiphon was forgotten for centuries afterwards until European explorers rediscovered it in the 19th century CE. No attempts at excavation or restoration were made, however, and in 1888 CE the banks of the Tigris overflowed during a flood and washed away large parts of the remaining structure (the imperial palace and throne room adjoining Taq Kasra). 19th-century CE drawings of the site show the central building and arch largely intact before the flood while significantly damaged afterwards.

The Iraqi government under Saddam Hussein began restoration efforts in the 1980's CE as part of their policy to rebuild ancient sites (such as Babylon) in honor of the past and to attract tourism to the country but these efforts were stopped by the Persian Gulf War of 1991 CE. Restoration efforts were not continued until c. 2004 CE which resulted in the reconstruction and stabilization of the northern section of the palace and Taq Kasra. A Czech company by the name of Avers was contracted to restore the site and completed their work in 2017 CE but, two years later, their work collapsed, damaging Taq Kasra further.

Presently, the ruins of Ctesiphon rise from a small oasis in the village of Salman Pak, 22 miles (35 km) southeast of Baghdad. There has been no security or any kind of authoritative agency regularly on site since the early 1990's CE so vandalism, as well as visitors climbing on Taq Kasra to take “selfies”, have damaged the site further. Taq Kasra now rises over the empty shell of the formerly opulent throne room of marble floors, carpets, and friezes and the entire ruin continues to deteriorate with no plans presently implemented to reverse this course.