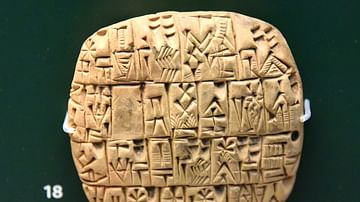

Cuneiform is a system of writing first developed by the ancient Sumerians of Mesopotamia c. 3500 BCE. It is considered the most significant among the many cultural contributions of the Sumerians and the greatest among those of the Sumerian city of Uruk, which advanced the writing of cuneiform c. 3200 BCE and allowed for the creation of literature.

The name comes from the Latin word cuneus for wedge owing to the wedge-shaped style of writing. In cuneiform, a carefully cut writing implement known as a stylus is pressed into soft clay to produce wedge-like imprints that represent word-signs (pictographs) and, later, phonograms or word-concepts (closer to a modern-day understanding of a word). All of the great Mesopotamian civilizations used cuneiform until it was abandoned in favour of the alphabetic script at some point after 100 BCE, including:

When the ancient cuneiform tablets of Mesopotamia were discovered and deciphered in the late 19th century, they would literally transform human understanding of history. Prior to their discovery, the Bible was considered the oldest and most authoritative book in the world and nothing was known of the ancient Sumerian civilization.

The German philologist Georg Friedrich Grotefend (l. 1775-1853) first deciphered cuneiform prior to 1823, and his work was furthered by Henry Creswicke Rawlinson (l. 1810-1895), who deciphered the Behistun Inscription in 1837, as well as the works of Reverend Edward Hincks (l. 1792-1866) and Jules Oppert (l. 1825-1905). The brilliant scholar and translator George Smith (l. 1840-1876), however, contributed significantly to the understanding of cuneiform with his translation of The Epic of Gilgamesh in 1872. This translation allowed other cuneiform tablets to be interpreted more accurately which overturned the traditional understanding of the biblical version of history of the time and made room for scholarly, objective explorations of the history of the Near East to move forward.

Early Cuneiform

The earliest cuneiform tablets, known as proto-cuneiform, were pictorial, as the subjects they addressed were more concrete and visible (a king, a battle, a flood) and were developed in response to the need for long-distance communication in trade. Sophisticated compositions were unnecessary since all that was required was an understanding of the type and quantity of goods shipped, their price, and the name and location of the seller. Scholar Jeremy Black comments on early cuneiform:

For centuries after the first appearance of writing in southern Iraq in the late fourth millennium BCE, it served an exclusively administrative function. Cuneiform was a mnemonic device designed to aid accountants and bureaucrats, rather than a vehicle for high art. (xlix)

These early pictographs came to be replaced by phonograms (symbols representing sounds) in the city of Uruk by c. 3200 BCE. Cuneiform had developed in complexity by the time of the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE) as, once the craft of writing was understood, people found more concepts they wanted to express and preserve for the future. Once writing was discovered, the ancient Sumerians sought to record virtually all of the human experience.

Part of that experience naturally touched on the origin of humanity, which then suggested the origin of all aspects of the human experience. The goddess Nisaba, formerly an agricultural deity, now became the goddess of writing and accounts – even the divine scribe of the gods – in response to the development of the written word. As the subject matter became more intangible (the will of the gods, creation, the afterlife, the quest for immortality), the script became more complex so that, before 3000 BCE, it needed streamlining.

The representations on tablets were simplified, and the strokes of the stylus conveyed word-concepts (honor) rather than word-signs (an honorable man). The written language was further refined through the rebus, which isolated the phonetic value of a certain sign so as to express grammatical relationships and syntax to determine the meaning. In clarifying this, the scholar Ira Spar writes:

This new way of interpreting signs is called the rebus principle. Only a few examples of its use exist in the earliest stages of cuneiform from between 3200 and 3000 B.C. The consistent use of this type of phonetic writing only becomes apparent after 2600 B.C. It constitutes the beginning of a true writing system characterized by a complex combination of word-signs and phonograms—signs for vowels and syllables—that allowed the scribe to express ideas. By the middle of the Third Millennium B.C., cuneiform primarily written on clay tablets was used for a vast array of economic, religious, political, literary, and scholarly documents. (1)

Development of Cuneiform

One no longer had to struggle with the meaning of a pictograph; one now read a word-concept, which more clearly conveyed the meaning of the writer. The number of characters used in writing was also reduced from over 1,000 to 600 in order to simplify and clarify the written word. The best example of this is given by scholar Paul Kriwaczek who notes that in the time of proto-cuneiform:

All that had been devised thus far was a technique for noting down things, items and objects, not a writing system. A record of 'Two Sheep Temple God Inanna' tells us nothing about whether the sheep are being delivered to, or received from, the temple, whether they are carcasses, beasts on the hoof, or anything else about them. (63)

Cuneiform developed to the point where it could be made clear, to use Kriwaczek's example, whether the sheep were coming from or going to the temple, for what purpose, and whether they were living or dead. During the Early Dynastic Period, scribal schools were established to preserve, teach, and further develop the craft of writing. These schools were known as edubba ("House of Tablets") and were initially established and operated out of private homes. The teacher (supervisor) made the rules for each individual edubba at first, and these rules were strictly enforced. The edubba later developed and spread throughout Sumer and, it seems, operated out of buildings expressly designated for the purpose of education.

Boys of the upper class (and sometimes girls) would enter the edubba around the age of eight and continue their studies for the next twelve years. The curriculum progressed from the simplest act of manipulating a moist clay tablet and stylus to forming words and then sentences. The act of writing in cuneiform was not as simple as just holding a piece of clay and making impressions in it. One had to constantly turn the tablet as one was writing to make the marks correctly.

Students were first shown how to simply make the vertical, horizontal, and oblique wedge marks clearly, and they practiced this exercise until they had mastered how to do it properly to the correct depth and dimension. Once the skill of manipulating both clay tablet and stylus was mastered, students moved on to learn characters that conveyed meaning and then produce sentences. While students were mastering the craft of writing, they were also instructed in mathematics, accounting, history, religion, and the values of their culture. Scholar Samuel Noah Kramer comments:

In order to satisfy this pedagogical need, the Sumerian scribal teachers devised a system of instruction which consisted primarily in linguistic classification – that is, they classified the Sumerian language into groups of related words and phrases and had the students memorize and copy them until they could reproduce them with ease. In the third millennium BCE, these "textbooks" became increasingly more complete, and gradually grew to be more or less stereotyped and standard for all the schools of Sumer. Among them we find long lists of names of trees and reeds: of all sorts of animals, including insects and birds; of countries, cities, and villages; of stones and minerals. These compilations reveal a considerable acquaintance with what might be termed botanical, zoological, geographical, and mineralogical lore – a fact that is only now beginning to be realized by historians of science. (History, 6)

Students progressed through their stages of education until they reached the level of the Tetrad (compositions of four) and Decad (compositions of ten) which were studied, memorized, and copied repeatedly. The Tetrad was comprised of simple texts, including the Hymn to Nisaba, while the Decad's texts were more complex in both composition and meaning. After the Decad, a student was expected to master even more complex compositions, such as A Supervisor's Advice to a Young Scribe or The Curse of Agade prior to graduation. Compositions were usually concluded with praise to Nisaba in gratitude for her inspiration and encouragement.

By this progression, literature not only developed but was made available for comment and criticism in written form while, in the process, the history of Mesopotamian civilization and culture, in every era, was preserved. By the time of the priestess-poet Enheduanna (l. 2285-2250 BCE), who wrote her famous hymns to Inanna in the Sumerian city of Ur, cuneiform was sophisticated enough to convey emotional states such as love and adoration, betrayal and fear, longing and hope, as well as the precise reasons why the writer might be experiencing such states.

Cuneiform could also express the human fear of death and hope of a life beyond, the tales of the creation of the world, the relationship between humans and their gods, and the devastation of existential despair when it seemed as though the gods had disappointed one's hopes and expectations. Cuneiform writing expressed in tangible form the whole of the human experience for the first time in history. Cuneiform can be understood, in fact, as the beginning of human historical documentation.

Cuneiform Decipherment & Impact

The great literary works of Mesopotamia such as the Atrahasis, The Descent of Inanna, The Myth of Etana, the Enuma Elish, and the famous Epic of Gilgamesh were all written in cuneiform and were completely unknown until the mid-19th century when men like George Smith, the Reverend Edward Hincks, Jules Oppert, and Rawlinson deciphered the language and translated it. Kramer writes:

The Sumerian literary documents range in size from large twelve-column tablets inscribed with hundreds of compactly written lines of text to tiny fragments run into the hundreds and vary in length from hymns of less than fifty lines to myths close to a thousand lines. As literary products, the Sumerian belles-lettres rank high among the aesthetic creations of civilized man. They compare not too unfavorably with the ancient Greek and Hebrew masterpieces and, like them, mirror the spiritual and intellectual life of an ancient culture which would otherwise have remained largely unknown. Their significance for a proper appraisal of the cultural and spiritual development of the entire ancient Near East can hardly be overestimated. (Sumerians, 166)

Even so, as noted, these works were entirely unknown until the mid-19th century. Rawlinson's translations of Mesopotamian texts were first presented to the Royal Asiatic Society of London in 1837 and again in 1839. In 1846, he worked with the archaeologist Austin Henry Layard in his excavation of Nineveh and was responsible for the earliest translations from the library of Ashurbanipal discovered at that site.

Edward Hincks focused on Persian cuneiform, establishing its patterns and identifying vowels among his other contributions. Jules Oppert identified cuneiform's origins and established the grammar of Assyrian cuneiform. George Smith was responsible for deciphering The Epic of Gilgamesh and, in 1872, famously, the Mesopotamian version of the Flood Story, which until then was thought to be original to the biblical Book of Genesis.

Many biblical texts were thought to be original until cuneiform was deciphered. The Fall of Man and the Great Flood were understood as literal events in human history dictated by God to the author (or authors) of Genesis but were now recognized as Mesopotamian myths which Hebrew scribes had embellished on from The Myth of Etana and the Atrahasis. The biblical story of the Garden of Eden could now be understood as a myth derived from the Enuma Elish and other Mesopotamian works. The Book of Job, far from being an actual historical account of an individual's unjust suffering, could now be recognized as a literary motif belonging to a Mesopotamian tradition following the discovery of the earlier Ludlul-Bel-Nemeqi text which relates a similar story.

The concept of a dying and reviving god who goes down into the underworld and then returns to life, presented as a novel concept in the gospels of the New Testament, was now understood as an ancient paradigm first expressed in Mesopotamian literature in the poem The Descent of Inanna. The very model of many of the narratives of the Bible, including the gospels, could now be read in light of the discovery of Mesopotamian naru literature which took a figure from history and embellished upon his achievements in order to relay an important moral and cultural message.

Prior to this time, as noted, the Bible was considered the oldest book in the world, and the Song of Solomon was thought to be the oldest love poem, but all of that changed with the discovery and decipherment of cuneiform. The oldest love poem in the world is now recognized as The Love Song of Shu-Sin dated to 2000 BCE, long before The Song of Solomon was written. These advances in understanding were all made by the 19th-century archaeologists and scholars sent to Mesopotamia to substantiate biblical stories through physical evidence, but, in fact, what they discovered was precisely the opposite of what they had been sent to find.

Conclusion

Along with other Assyriologists (among them, T. G. Pinches and Edwin Norris), Rawlinson spearheaded the development of Mesopotamian language studies, and his Cuneiform Inscriptions of Ancient Babylon and Assyria, along with his other works, became the standard reference on the subject following their publication in the 1860s and remain respected scholarly works into the present day.

George Smith, regarded as an intellect of the first rank, died on a field expedition to Nineveh in 1876 at the age of 36. Smith, a self-taught translator of cuneiform, made his first contributions to deciphering the ancient writing in his early twenties, and his death at such a young age has long been regarded as a significant loss to the advancement in translations of cuneiform in the 19th century.

The literature of Mesopotamia significantly informed written works which came after. Mesopotamian literary motifs can be detected in the works of Egyptian, Hebrew, Greek, and Roman works and still resonate in the present day through the biblical narratives which they inform. When George Smith deciphered cuneiform he dramatically changed the way human beings would understand their history.

The accepted version of the creation of the world, original sin, and many of the other precepts by which people had been living their lives were all challenged by the revelation of Mesopotamian – largely Sumerian – literature. Since the discovery and decipherment of cuneiform, the history of civilization and human progress has been radically revised from the understanding of only 200 years ago, and further revisions are expected as more cuneiform tablets are discovered and translated for the modern age.