The American Revolution (1765-1789) was a period of political upheaval in the Thirteen Colonies of British North America. Initially a protest over parliamentary taxes, it blossomed into a rebellion and led, ultimately, to the birth of the United States. Rooted in the ideas of the Enlightenment, the Revolution played an important role in the emergence of modern Western democracies.

Origins: Parliament & the American Identity

In February 1763, the Seven Years' War – or the French and Indian War as the North American theater was called – came to an end. As part of the peace agreement, the vanquished Kingdom of France ceded its colony of New France (Canada) as well as all its colonial territory east of the Mississippi River to its victorious rival, Great Britain. While this left Britain as the dominant colonial power in North America, this newfound supremacy came at a cost, namely a massive war debt. To offset the debt, the British Parliament decided to levy new taxes on the Thirteen Colonies along the eastern seaboard of North America. Much of the war had been fought defending these colonies, after all, and Parliament decided that the colonists should help shoulder the empire's financial burden.

Prior to this decision, Parliament had adhered to an unofficial policy of 'salutary neglect' when dealing with the American colonies. This meant that, despite their royal governors, the colonies were largely left to manage their own affairs, with colonial legislatures overseeing governance and taxation. The influence of these legislatures often equaled if not eclipsed the power of the colony's royally appointed governor. Due to differing foundational and developmental circumstances, each colony maintained its own identity – the Puritan society of New England, the Dutch origins of New York, and the tobacco economy of Virginia, for example, all influenced the formation of their colonial identities. Despite viewing themselves as separate from one another, the colonies were loosely bound by their shared ties to Britain and had united in common defense multiple times during the last century of colonial wars.

At the same time, the American colonists considered themselves Britons, and proudly so. After the Glorious Revolution of 1689, and the constitutional reforms that went with it, the British were viewed as the freest people in the world; they were guaranteed a right to representative government (Parliament) as well as the right to self-taxation. The colonists believed that these 'rights of Englishmen' extended to them, as befitting of their English blood and allegiance to the English king; indeed, many of these rights were echoed in the colonies' own charters. The idea that Parliament could directly tax the colonies, therefore, went against this notion; since no Americans were represented in Parliament, Parliament had no constitutional authority to tax them (i.e. taxation without representation). Parliament, of course, disagreed, arguing that the Americans were virtually represented, as was the case with the thousands of Englishmen who owned no property and could not vote. It was this fundamental disagreement over the Americans' rights and liberties – expressed in the guise of taxation – that lay at the heart of the American Revolution and the birth of the United States.

The Gathering Storm: 1763-1770

The first indicator that the policy of salutary neglect might come to an end was in October 1763, when King George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820) issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763. This forbade the colonists from settling in the newly acquired lands west of the Appalachian Mountains, in an effort to restrict unnecessary conflict between the colonists and the Native peoples of North America (additionally, the British government feared that westward expansion would disrupt the mercantile system by giving the colonies more opportunities for economic independence). This angered many colonists, particularly veterans of the French and Indian War who had been promised land in the Ohio Country and wealthy Virginian land speculators who had wished to expand into the territory. The Royal Proclamation caused a few grumbles that were only magnified the following year when Parliament passed the Sugar Act. This act enforced the existing tax on the molasses trade, which colonial merchants frequently circumvented by means of smuggling; since molasses was so important to the economies of the New England colonies, the Americans had viewed its smuggling as a victimless crime and resented the meddling of Parliament.

While the Royal Proclamation and the Sugar Act both heralded an end to salutary neglect, the first real nail in the coffin would come in March 1765, when Parliament passed the Stamp Act. This was the first of the direct taxes meant to help pay off the war debt and consisted of a tax in the form of a stamp, placed on all paper items such as legal documents, newspapers, calendars, and playing cards. Though the Stamp Act was not slated to go into effect until November, the mere news of its implementation caused outrage throughout the colonies. In Massachusetts, Samuel Adams and James Otis, Jr., took the lead in resisting the tax, arguing that the Stamp Act violated the colonists' 'rights as Englishmen' and that payment would be tantamount to tributary slavery. In Virginia, Patrick Henry spearheaded the passage of the Virginia Resolves through the House of Burgesses, which effectively declared that no one had the right to tax Virginia except Virginians. On 14 August, riots broke out in Boston, led by a group of political agitators called the Sons of Liberty, as protestors burned effigies and stormed the homes of the colony's stamp distributor and lieutenant governor; similar riots broke out in Newport, Rhode Island.

One of the most significant outcomes was the Stamp Act Congress, in which 9 of the 13 colonies sent delegates to New York City to coordinate a response; this was the first instance of unified colonial resistance to Britain. Parliament had not expected such a furious backlash and, in January 1766, repealed the Stamp Act. However, just so it would not appear as though it were conceding the point to the Americans, Parliament also passed the Declaratory Act, which stipulated that Parliament had the power to legislate on behalf of all Britain's colonies “in all Cases whatsoever” (Middlekauff, 118). Using the Declaratory Act as its justification, Parliament passed another series of direct taxes – this time on glass, lead, paint, paper, and tea – in the Townshend Acts of 1767-68. The colonists once again resisted; colonial legislatures condemned the taxes as unconstitutional, while American merchants made nonconsumption agreements to boycott British imports. Sons of Liberty continued to terrorize tax collectors and Tories – as those loyal to Parliament were referred – with methods such as tarring and feathering.

On 9 May 1768, the Liberty, a sloop belonging to popular Boston merchant John Hancock, was seized by British customs officials, on the pretext that it had been carrying smuggled goods. When British sailors arrived to take custody of the sloop, a riot broke out along the wharves of Boston Harbor; things got so violent that the five British customs officials were forced to seek shelter on Castle William in the harbor. When news of the riots reached London, Parliament decided to send soldiers to Boston to restore order. On 1 October 1768, the soldiers arrived in the city and made camp on Boston Commons; tensions between the soldiers and colonists escalated over the following year until 5 March 1770, when nine British soldiers fired into an angry mob of colonists that had been accosting them. Five colonists were killed in what would become known as the Boston Massacre. Although most of the soldiers were ultimately acquitted, thanks to the legal defense of John Adams, the incident became excellent propagandic fodder for the Whigs, or Patriots, who used it to present British soldiers as barbaric.

Escalation: 1770-1775

Shortly after the Boston Massacre, word reached the colonies that all the Townshend Acts had been repealed, except for a single tax on tea. Aside from a few scattered instances of violence – such as the Gaspee Affair of 1772, when Rhode Islanders set fire to a Royal Navy sloop – tensions significantly decreased, and it seemed as though things might go back to normal. Then, in May 1773, Parliament passed the Tea Act; seemingly innocuous enough, this gave the British East India Company a monopoly on the tea trade in the colonies. But all the East India Company's tea was still subject to the tea tax; because of this, the Patriots viewed the Tea Act as an underhanded way to get them to pay the tax and thereby acknowledge the supremacy of Parliament. This culminated in the Boston Tea Party when, on 16 December 1773, a group of Sons of Liberty, disguised as Mohawks, dumped 342 crates of East India Company Tea into Boston Harbor.

For Parliament, this was the last straw. In early 1774, it passed the Coercive Acts – known in the colonies as the Intolerable Acts – meant to punish Massachusetts for its insolence. These acts included the closure of Boston Harbor to commerce until the East India Company was repaid for the loss of cargo, as well as the suspension of representative government in Massachusetts, and allowed for British soldiers to quarter in unoccupied American buildings. In September 1774, every colony except Georgia sent delegates to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Hoping that their quarrel was with Parliament alone, the Congress drew up a 'Petition to the King' in which they listed their grievances and asked for help from George III. The Congress also agreed to another nonimportation agreement on British goods and allowed the New England militias to begin preparing for potential conflict with British soldiers. The Congress disbanded on 26 October, in the understanding that it would reconvene if the situation had not improved by the following spring.

Meanwhile, the New England colonies became a tinderbox, as local militias began training for war and stockpiling munitions. General Thomas Gage, military governor of Massachusetts, knew he did not have enough soldiers to suppress an open rebellion and sought to postpone a war for as long as possible by periodically seizing weapon stockpiles from the Patriots. Early on the morning of 19 April 1775, a detachment of British soldiers was on its way to seize one such stockpile in Concord, Massachusetts, when they were confronted by 77 Patriot militiamen on Lexington Green. A shot rang out – no one knows who fired it – resulting in eight dead and ten wounded militiamen before the British continued on their way. At Concord, they were met with hundreds more militiamen. After failing to find any weapons, the British detachment retreated to Boston, harried the entire way by the Patriots. By the time they got to Boston, nearly 15,000 New England militiamen were gathered outside the city, ready to lay siege. The American Revolutionary War had begun.

Fighting for Independence: 1775-1783

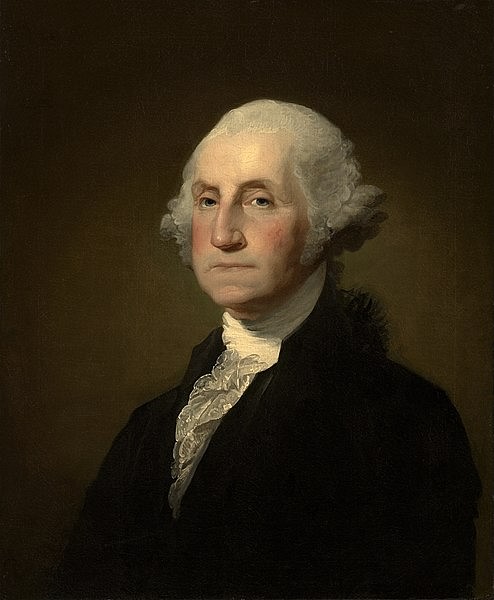

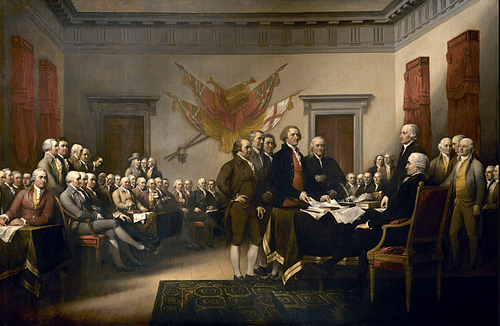

Shortly after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia to take charge of the rebellion. It adopted the Continental Army and named George Washington as commander-in-chief, all while trying to de-escalate tensions with Britain. On 5 July 1775, it sent the Olive Branch Petition in a last-ditch attempt at peace. The petition expressed loyalty to King George III while blaming the war entirely on the tyranny of Parliament. The king did not even read the petition, however; instead, he issued a proclamation in October 1775 declaring the colonies in open rebellion. The realization that the king was not sympathetic to their plight was a shock to many Americans, who wondered what to do next; the answer came in the form of Thomas Paine's seminal pamphlet Common Sense, in which he urged the colonies to declare independence. The idea, unthinkable only a year before, soon gained traction throughout the colonies. In Congress, John Adams and Richard Henry Lee spearheaded the push for separation from Britain. Finally, on 2 July 1776, Congress voted in favor of independence and adopted the Declaration of Independence two days later.

Meanwhile, the war was raging on. Initially, the rebels performed well at the Battle of Bunker Hill (17 June 1775) and the capture of Fort Ticonderoga (10 May 1775) and won the Siege of Boston (April 1775 to March 1776). But these feelings of victory were offset by the failed American invasion of Quebec in December 1775, and by Washington's defeat at the Battle of Long Island on 27 August 1776, which culminated in the British capture of New York City. For the rest of the autumn, Washington was chased through lower New York and New Jersey, his army dwindling to barely 3,000 men through attrition. But just when it seemed as though the Continental Army was on the verge of defeat, Washington crossed the Delaware River to win a series of quick victories at the Battle of Trenton (26 December 1776) and Battle of Princeton (3 January 1777). These actions staved off defeat and galvanized renewed support for the Revolution.

The next year, the British dealt Washington two major defeats at the Battle of Brandywine (11 September 1777) and the Battle of Germantown (4 October) before occupying the US capital of Philadelphia, forcing Congress to seek shelter in the nearby town of York. The British soon realized that their occupation of Philadelphia had a minimal effect on Patriot morale, and they were unable to hold the city, abandoning it in June 1778. Meanwhile, the Patriots won a stunning victory at the Battles of Saratoga (19 September and 7 October 1777), forcing the surrender of an entire British army that had been pushing south from Canada. The Saratoga Campaign ultimately persuaded France to enter the war as a US ally. Eager to get revenge for their loss in the Seven Years' War, France provided the Patriots with money, arms, troops, and ships; the entry of France, and later Spain and the Dutch Republic, transformed the rebellion into a global conflict. Britain was forced to spread its military resources thin to defend its more valuable colonies in the West Indies, giving the Patriots much-needed breathing room.

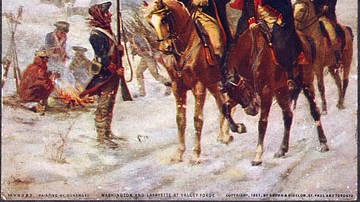

In 1778, the Continental Army emerged from its winter quarters at Valley Forge as a more disciplined and efficient fighting force. It fought the British army to a standstill at the Battle of Monmouth (28 June 1778), shortly after the British had been forced to abandon Philadelphia. The focus of the war then shifted to the American South, where the British won some important victories at the Siege of Charleston (29 March to 12 May 1780) and the Battle of Camden (16 August 1780). However, thanks to the resilience of Patriot militia forces and the leadership of General Nathanael Greene, the Patriots gradually wrested the South away from British control. Finally, on 19 October 1781, British General Lord Charles Cornwallis surrendered to Washington, after having been trapped by Franco-American forces at the Siege of Yorktown. This ended the active phase of the war and, in September 1783, American and British diplomats signed the Treaty of Paris of 1783, which recognized the independence of the United States.

Forging a Republic: 1783-1789

The war may have been over, but the infant republic was still in dire straits. The Articles of Confederation, the framework of government in effect since 1781, intentionally left the central government weak to ensure the sovereignty of the states; however, this left the central government unable to raise its own taxes and pay off its debts. Additionally, the new Continental currency had become practically worthless, leading to further turmoil. Toward the end of the war, Continental soldiers mutinied after not getting the payment they had been promised, while heavy taxation led farmers in western Massachusetts to revolt in Shays' Rebellion (1786-87). To make matters worse, Britain sensed the United States' weakness and refused to pull its troops from six forts on the western frontier, in violation of the Treaty of Paris.

To many Americans, it was clear that a stronger central government was needed if the country hoped to survive. In May 1787, the Constitutional Convention was held in Philadelphia; initially intended to merely revise the Articles of Confederation, the Convention ended up drafting an entirely new framework of government, the United States Constitution. This created a stronger federal government split into three branches – executive, legislative, and judicial – which would each exert checks and balances on the others. When the Convention disbanded in September, the Constitution was sent to the states for ratification, leading to a fierce debate between the Federalists, who supported ratification, and the Anti-Federalists, who thought that the proposed national government would be too powerful and might threaten American liberties. Arguing in favor of ratification, a series of essays were penned by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, collectively called the Federalist Papers.

By 21 June 1788, the Constitution had been ratified by the necessary nine states (although in many cases, it had only been ratified by a slim margin). In the US presidential election of 1789, George Washington was unanimously elected as the first president of the United States, with John Adams elected as his vice president. The First Congress reached a quorum in early April 1789, and Washington was inaugurated on 30 April at Federal Hall in New York City. With his inauguration, the long process of the American Revolution finally came to an end – from the first riots against the perceived tyranny of Parliament in 1765 to the implementation of the US Constitution in 1789. The Revolution, which gave birth to one of the first modern Western democracies, remains a significant chapter in both US and world history.