Edessa (modern Urfa), located today in south-east Turkey but once part of upper Mesopotamia on the frontier of the Syrian desert, was an important city throughout antiquity and the Middle Ages. A city within the Seleucid Empire, then capital of the kingdom of Osroene, then a Roman provincial city, Edessa found itself perennially caught between empires, especially between Rome and Parthia. Conquered by the Muslim Arabs c. 638 CE, it would be incorporated into the Byzantine Empire from 944 CE. Still a major Christian and cultural centre and capital of the County of Edessa, the city's capture by the Muslim leader Zangi in 1144 CE, was the original motivation for the launch of the unsuccessful Second Crusade (1147-1149 CE) in order to reclaim it for Christendom. Following its destruction by the Muslim leader Nur ad-Din (sometimes also given as Nur al-Din) in 1146 CE, Edessa largely disappears from history, but today many fine mosaics from the city survive and attest to the wealth of some of Edessa's citizens in Late Antiquity and the early medieval period.

Early History

Edessa, then known as Adme, was an ancient settlement, chosen for its advantageous position on a fertile plain with abundant water from a nearby branch of the Euphrates River while also being protected by a ring of hills to the south. The site was a cult centre for the moon god mentioned in both neo-Assyrian and neo-Babylonian sources. Seleucus I (358-281 BCE), one of Alexander the Great's Macedonian commanders who established the Seleucid Empire (312-63 BCE) in Asia, re-founded the city as a military settlement in 304 BCE. Seleucus gave it the new name of Edessa, after the original name of the ancient capital of Macedonia. In the 2nd century BCE, Edessa became the capital and royal residence of Osroene, a region of the Seleucid Empire in north-west Mesopotamia which declared itself an independent kingdom (traditional date 132 BCE). The population of Edessa, like Osroene in general at this time, was a mix of Greeks, Parthians, and Semitic Arameans. Although the kingdom was, in reality, a vassal state of Parthia, it proved a useful buffer zone between that empire and the emerging Roman Empire.

Roman Edessa

As the power of Rome grew, Osroene became a dependency within the Roman Empire, with Pompey the Great (106-48 BCE) notably granting King Abgar II (r. 68-53 BCE) an enlarged territory. The religion practised in Osroene was pagan, but much closer to that of Parthia than Rome. Emperor Trajan (r. 98-117 CE) was a notable guest, visiting Edessa on his tour of the region when he was hosted by King Abgar VII (r. 109-116 CE). Then, after the successful campaigns of the emperor Lucius Verus (r. 161-169 CE), who sacked Edessa, the city was made into a Roman colony and, thereafter, prospered, even minting its own coinage. The city once again benefitted from its favourable position on trade routes, being on the only official route between the Roman and Parthian Empires (247 BCE - 224 CE). Roman emperor Caracalla (r. 211-217 CE) was rather less friendly and summoned Abgar VIII to Rome and imprisoned him in the hopes of turning Edessa into a useful platform from which to launch an invasion of Parthia, but nothing came of the plan.

In 242 CE Edessa became the capital of the Roman province of Osroene. The Sasanian Empire (224-651 CE), the successor to the Parthians, was equally ambitious for new territory, and in 260 CE Shapur I (r. 240-272 CE) attacked Antioch and then captured Roman emperor Valerian (r. 253-260 CE) at Edessa when he was seeking peace terms in one of Rome's most embarrassing military defeats in its long history.

Byzantine/Christian Edessa

At the same time that Edessa was the subject of imperial rivalries, the city still managed to become a great centre of culture and learning, especially of Christian scholarship. The city had been an early adopter of Christianity in the 2nd century CE with the first recorded church being already active in 202 CE. Edessa became the most important bishopric in Syria. Famous residents included Joshua the Stylite, the chronicler of 6-7th century CE regional history, and Theodore of Edessa, the legendary missionary bishop (c. 776 - c. 856 CE). Movses Khorenatsi, the famous 5th-century CE Armenian historian spent some time studying at Edessa, as did Mesrop Mashtots (360/370 - c. 440 CE) who invented the Armenian alphabet in 405 CE. Edessa was also a popular stop for Christian pilgrims, the city boasting many holy relics such as the skeletal remains of Thomas the Apostle. Another important relic, and one considered of vital importance to the city's well-being, was the Mandylion icon.

The Mandylion Icon of Edessa

The Mandylion icon was actually a scarf or shroud which was considered to have on it the image of Jesus Christ. According to the legend which is first recorded in the 6th century CE, Abgar V, the early 1st-century CE king of Edessa, became seriously ill and he called on Jesus Christ to cure him. Unable to visit in person, Christ pressed his face against a cloth, which left an impression, and then sent the cloth to Abgar. On receiving the gift, the king was miraculously cured and he became a Christian. Even more significantly, accompanying the Mandylion was a letter which, itself considered a holy relic, stated that so long as the city was in possession of the Mandylion it would never be taken by an enemy army.

It seems that the Mandylion story was based on the actual conversion to Christianity of a later king of the same name, Abgar IX (r. 179-216 CE). Whatever the origins of the story, the important fact was that the people of Edessa, along with many others in the Christian world, believed it to be true. Further, the image on the miracle icon, probably the first relic its kind, was copied in many wall-paintings and domes in churches around Christendom as it became the standard representation known as the Pantokrator (All-Ruler) with Christ full frontal holding a Gospel book in his left hand and performing a blessing with his right. The image would also inspire the design of coins of the Byzantine Empire. The Mandylion had other influences, too, the icon being frequently cited in theological arguments for Christ's incarnation as a real man during the Middle Ages.

The Mandylion was taken from Edessa in 944 CE when John Kourkouas took it in exchange for lifting his siege of the city with the Byzantine emperor, Romanos I (r. 920-944 CE), officially promising not to attack it again. From there it was taken to the Great Palace of Constantinople. When Constantinople was sacked in 1204 CE during the Fourth Crusade (1202-1204 CE), the Mandylion was taken as a prize to France, where it was ultimately destroyed during the chaos of the French Revolution (1789-1799 CE).

Arab Conquest

Edessa was attacked several times over the centuries especially by the neighbouring Sasanids, notably in 503 CE by Kavad, king of Persia (r. 488-531 CE), although his siege was not successful (the Mandylion doing its job). In the on-off wars between Persia and the Byzantine Empire (the eastern half of the Roman Empire), Edessa was once more attacked in 544 CE, this time by Chosroes I (r. 531-579 CE), but again the city stood firm. Between 638 and 641 CE, it was a different story and Edessa fell under Arab control; it would not return to Byzantine rule until the Byzantine general John Kourkouas took it back in 944 CE. The city, nevertheless, remained an important Christian centre, especially in terms of translations, manuscript production, and education. The cathedral of Edessa was described by the 10th-century CE Arab scholar al-Maqdidis as "a wonder of the world" (Bagnall, 2306).

Edessa was lost and then recaptured by the Byzantines in 1032 CE thanks to the efforts of the general George Maniakes, but it remained, as ever, a bone of contention between rival empires; the local Muslim emirs attacking the city in 1036 and 1038 CE. Then a more permanent political situation was arrived at when the Seljuk Muslims won significant victories in Asia Minor against Byzantine armies, notably at the Battle of Manzikert in ancient Armenia in August 1071 CE. Edessa was to be handed over as part of the peace deal between the Seljuks and the captured Byzantine Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes (r. 1068-1071 CE), but, in the event, the Byzantines held on to it; such was its strategic importance.

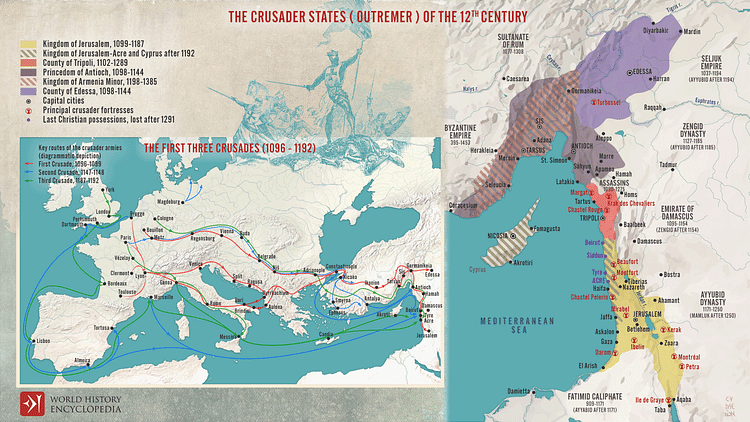

Around 1078 CE, the Seljuks created the Sultanate of Rum, but the gifted general Philaretos Brachamios managed to keep Edessa in Byzantine hands. The Seljuks would finally conquer Edessa in 1078 CE, but then the western armies of the First Crusade (1095-1102 CE) arrived on the scene and recaptured the city in 1098 CE, along with Jerusalem in 1099 CE.

The County of Edessa

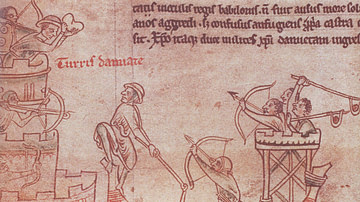

The victorious leaders of the First Crusade created several new states in the Middle East, the first amongst them was the County of Edessa. The county was established under dubious circumstances by Baldwin of Boulogne in March 1098 CE. Baldwin and his army of around 80 western knights (plus infantry) had actually been invited by Thoros, the Armenian ruler of Edessa, to come to his aid against the imminent arrival of a Muslim army from Mosul in Iraq. Baldwin had agreed to lend his support on the condition that he become Thoros' heir, but, on arrival, the Frenchman either joined or turned a blind eye to a dissident mob which lynched Thoros. Baldwin then created the first Latin State with himself as ruler. Meanwhile, the Muslim army, on hearing the news of the change in power and the fall of Antioch a day earlier after a long siege, withdrew.

The territory of the County of Edessa straddled the middle section of the Euphrates River, contained several important castles such as Ranculat and Ravendan, and provided valuable foodstuffs for the Latin East, as the Crusader-created states were known. Further, Edessa was a strategically important shield to Antioch further west and a strong platform from which to launch raids deeper into Muslim-held Mesopotamia. This area had previously been controlled by Christian Armenians, and although Baldwin had usurped political rule, there was, through many intermarriages, a mix of Frankish and Armenian nobility, making the County of Edessa the most integrated of the four Crusader-created states the region. Edessa, though, remained a vassal state to the more important and powerful Latin polities of Antioch and Jerusalem.

Edessa & the Second Crusade

In the 12th century CE, Edessa, with its wealth and rich history, attracted the attention of Imad ad-Din Zangi (r. 1127-1146 CE), the Muslim independent ruler of Mosul and Aleppo in Syria. Zangi encircled the city and had his men undermine one of the defensive walls, which consequently collapsed. After a four-week struggle, the city was captured by Zangi on 24 December 1144 CE, which Muslims described as "the victory of victories" (Asbridge, 226). Western Christians were killed or sold into slavery while eastern Christians were permitted to remain. Before the fall, the Christians of Edessa had appealed for help to the west, an appeal later given some emotional propaganda by such Christian writers as Michael the Syrian (d. 1199 CE):

Edessa remained a desert: a moving sight covered with a black garment, drunk with blood, infested by the very corpses of its sons and daughters! Vampires and other savage beasts ran and entered the city at night in order to feast on the flesh of the massacred, and it became the abode of jackals; for none entered there except those who dug to discover treasures. (quoted in Riley-Smith, 230-1)

The Arab sources give a rather different view, such as the following note by Ibn al-Athir (1160-1232 CE):

When Zangi inspected the city he liked it and realized that it would not be sound policy to reduce the place to ruins…The city was restored to its former state, and Zangi installed a garrison to defend it. (ibid, 231)

In response to the fall of Edessa and the general threat to the Latin states in the Levant, Pope Eugenius III (r. 1145-1153 CE) formally called for a crusade, what is now known as the Second Crusade, on 1 December 1145 CE. The Crusade was led by the German king Conrad III (r. 1138-1152 CE) and Louis VII, the king of France (r. 1137-1180 CE) but before the western army could arrive, Edessa was in still greater trouble. Nur ad-Din (r. 1146-1174 CE), Zangi's successor after his death in September 1146 CE, defeated the Latin leader Joscelin II's attempt to retake Edessa. Once again the city was sacked to celebrate Nur ad-Din's new power. All the Christian male citizens of the city were slaughtered, and the women and children were sold into slavery, just as their western fellows had been two years before. To ensure Edessa could not be used again by the enemy, its fortifications were systematically destroyed.

After the Crusader army's defeat at Dorylaion in Asia Minor on 25 October 1147 CE and the failed siege of Damascus in July 1148 CE, the Second Crusade was abandoned and Edessa left to its fate. Nur ad-Din continued to consolidate his empire, and he took Antioch on 29 June 1149 CE and then captured Raymond, the Count of Edessa, thus bringing an end to the County of Edessa in 1150 CE.

Archaeological Remains

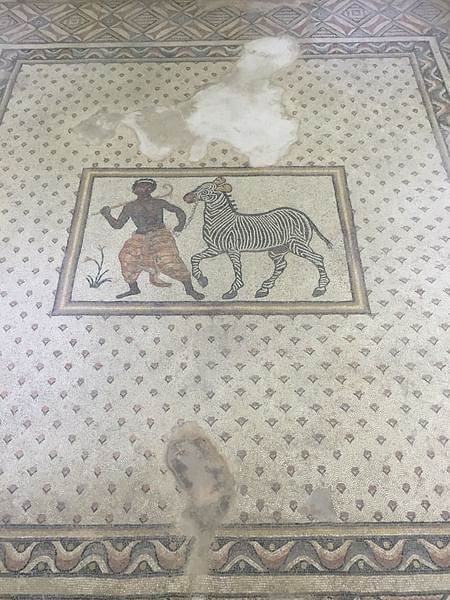

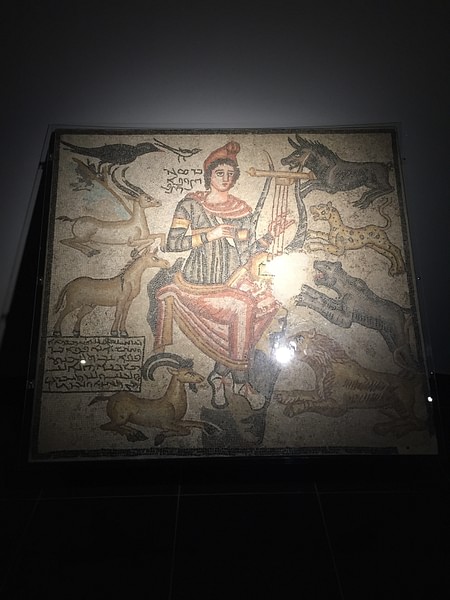

There are, unfortunately, precious few monumental remains from Edessa's long and eventful history still visible today. Perhaps most striking are two columns, each around 18.2 (60 ft) high, which stand on the city's citadel. The columns were once topped with statues of Abgar VIII and his queen but date to the 3rd-4th century CE as indicated by a Syriac inscription on one of the bases. Belonging to a similar date are the remains of two large fish pools, once used to keep carp for religious dedications to a fertility goddess. There are some portions of the city's fortification walls still in situ and many tombs and mosaics from Late Antiquity and early-medieval Edessa. The majority of these mosaics are from the rich upper classes, and they often show scenes of daily life or representations of the tomb's occupants and their family.