Gilgamesh is the semi-mythic King of Uruk best known as the hero of The Epic of Gilgamesh (c. 2150-1400 BCE) the great Babylonian poem that predates Homer's Iliad and Odyssey by 1500 years and, therefore, stands as the oldest piece of epic world literature. Gilgamesh features in several Sumerian poems but is world-famous from the Mesopotamian epic.

Historical evidence for Gilgamesh's existence is found in inscriptions crediting him with the building of the great walls of Uruk (modern-day Warka, Iraq) which, in the story, are the tablets upon which he first records his quest for the meaning of life. He is also referenced in the Sumerian King List (c. 2100 BCE) and is mentioned by known historical figures of his time such as King Enmebaragesi of Kish (c. 2700 BCE), besides the legends which grew up around his reign.

The quest for the meaning of life, explored by writers and philosophers from antiquity up to the present day, is first fully explored in the Gilgamesh epic as the hero-king leaves the comfort of his city following the death of his best friend, Enkidu, to find the mystical figure Utnapishtim and eternal life. Gilgamesh's fear of death is actually a fear of meaninglessness, and although he fails to win immortality, the quest itself gives his life meaning.

Historical & Legendary King

Gilgamesh's father is said to have been the priest-king Lugalbanda (who is featured in two Sumerian poems concerning his magical abilities which predate Gilgamesh) and his mother the goddess Ninsun (also known as Ninsumun, the Holy Mother and Great Queen). Accordingly, Gilgamesh was a demigod who was said to have lived an exceptionally long life (the Sumerian King List records his reign as 126 years) and to be possessed of super-human strength.

Gilgamesh is widely accepted as the historical 5th king of Uruk who reigned in the 26th century BCE. His influence is thought to have been so profound that myths of his divine status grew up around his deeds and finally culminated in the tales that inform The Epic of Gilgamesh. Later Mesopotamian kings would invoke his name and associate his lineage with their own. Most famously, Shulgi of Ur (r. 2029-1982 BCE), considered the greatest king of the Ur III Period (2047-1750 BCE) in Mesopotamia, claimed Lugalbanda and Ninsun as his parents and Gilgamesh as his brother to elevate his standing among his subjects.

Known as Bilgames in Sumerian, Gilgames in Akkadian, and Gilgamos in Greek, his name may mean "the kinsman is a hero" or, according to scholar Stephen Mitchell, "The Old Man is a Young Man" (10). He is sometimes associated with the shepherd-god Dumuzi (Tammuz), an early dying and reviving god figure, legendary king of Uruk, and consort of Inanna/Ishtar, best known in the modern era from the Sumerian poem The Descent of Inanna. Dumuzi was seduced by Inanna/Ishtar and suffered for it by having to spend half the year in the underworld while Gilgamesh rejects her but also suffers through the loss of his friend.

Development of the Text

The Akkadian version of the text was discovered at Nineveh, in the ruins of the library of Ashurbanipal, in 1849 by the archaeologist Austin Henry Layard. Layard's expedition was part of a mid-19th century initiative of European institutions and governments to fund expeditions to Mesopotamia to find physical evidence to corroborate events described in the Bible. What these explorers found instead, however, was that the Bible – previously thought to be the oldest book in the world and comprised of original stories – actually drew upon much older Sumerian myths.

The Epic of Gilgamesh did likewise as it is informed by tales, no doubt originally passed down orally, and finally written down 700-1000 years after the historical king's reign. The author of the version Layard found was the Babylonian writer Shin-Leqi-Unninni (wrote 1300-1000 BCE) who was thought to be the world's first author known by name until the discovery of the works of the poet-priestess Enheduanna (l. 2285-2250 BCE), daughter of Sargon of Akkad (r. 2334-2279 BCE). Shin-Leqi-Unninni drew upon Sumerian sources to create his story and probably had a significant number to work from as Gilgamesh had been a popular hero for centuries by the time the epic was created.

In the Sumerian tale of Inanna and the Huluppu Tree (c. 2900 BCE), for example, Gilgamesh appears as her loyal brother who comes to her aid. Inanna (the Sumerian goddess of love and war) plants a tree in her garden with the hope of one day making a chair and bed from it. The tree becomes infested, however, by a snake at its roots, a female demon (lilitu) in its center, and an Anzu bird in its branches. No matter what, Inanna cannot rid herself of the pests and so appeals to her brother, Utu-Shamash, god of the sun, for help.

Utu refuses, and so she turns to Gilgamesh, who comes, heavily armed, and kills the snake. The demon and Anzu bird then flee, and Gilgamesh, after taking the branches for himself, presents the trunk to Inanna to build her bed and chair from. This is thought to be the first appearance of Gilgamesh in heroic poetry, and the fact that he rescues a powerful goddess from a difficult situation shows the high regard in which he was held even early on.

The early Sumerian tales eventually woven into The Epic of Gilgamesh are:

- Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld (also known as Gilgamesh and the halub tree)

- Gilgamesh and Huwawa

- Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven

- The Death of Gilgamesh

- The Flood Story (Eridu Genesis and later Atrahasis)

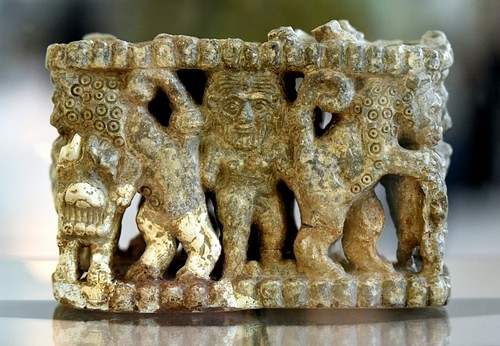

These tales represent him as a great hero, and the historical king was eventually accorded completely divine status as a god. He was regularly depicted as the brother of Inanna, one of the most popular goddesses in all of Mesopotamia. Prayers found inscribed on clay tablets address Gilgamesh in the afterlife as a judge in the Underworld comparable in wisdom to the famous Greek afterlife judges, Rhadamanthus, Minos, and Aeacus.

In the poem Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld (which draws on earlier myths including Inanna and the Huluppu Tree), Gilgamesh is given a firsthand account of the afterlife by Enkidu, who has returned from Ereshkigal's dark realm where he went to retrieve his friend's lost items. Depending on different interpretations, Enkidu may be a ghost who delivers this vision, making Gilgamesh the only living being to know what waits beyond death or, if Enkidu is understood to have survived his trip to the underworld, only one of two, not counting the divine Dumuzi.

The cuneiform tablets of the work discovered by Layard in 1849, and translated and published by George Smith in 1876, make up the standard version of the tale. Any modern translation relies on these eleven tablets but sometimes a twelfth is added relating Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld. This story is usually omitted, however, as Enkidu dies in Tablet 7 of the standard version, and his appearance in Tablet 12, as a servant and not Gilgamesh's friend, makes no sense.

When Tablet 12 is included in a translation, it is sometimes justified by the translator/editor claiming that Enkidu is a ghost who has returned from the land of the dead to tell Gilgamesh what he has seen. This interpretation is not supported by the text of the poem, however, in which Gilgamesh twice appeals to the gods for Enkidu's release from the underworld, saying he has not died but is being detained unlawfully. Most modern translators, therefore, rightly choose to leave Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld where it belongs: as a separate work composed long before the standard version of the epic, dated to the time of Shin-Leqi-Unninni.

Summary

The Epic of Gilgamesh begins with an invitation to the reader to engage in the story of the great king who, at first, is depicted as a proud and arrogant tyrant. He terrorizes his people, sleeps with the brides of his subjects on their wedding night, and consistently uses force to get his way in all things. The gods decide to humble him by creating the wild man, Enkidu. Hearing of Enkidu roaming in the outskirts of his realm, Gilgamesh suggests the temple prostitute Shamhat be sent to tame him, which she does.

Once tamed and introduced to civilization, Enkidu is outraged by the stories he hears of Gilgamesh and his arrogance and travels to Uruk to challenge him. Enkidu and Gilgamesh are considered an even match by the people, but after an epic battle, Enkidu is bested. He freely accepts his defeat, and the two become best friends and embark on adventures together.

In order to make his name immortal, Gilgamesh suggests they travel to the Cedar Forest to kill the monster-demon Humbaba ('demon' understood as 'supernatural entity', not an evil spirit). Humbaba has done nothing wrong and is favored by the gods for his protection of the forest, but this means nothing to Gilgamesh, who is only thinking of himself. Once the two friends have defeated Humbaba, he cries out for mercy, but Enkidu encourages Gilgamesh to kill him, which he does.

They return to Uruk where Gilgamesh prepares to celebrate his victory, putting on his finest clothes. This attracts the attention of Inanna/Ishtar who desires him. Ishtar tries to seduce Gilgamesh, but he rejects her, citing all the other men she has had as lovers who ended their lives poorly, including Dumuzi. Ishtar is enraged and sends her brother-in-law, the Bull of Heaven, down to earth to destroy Uruk and Gilgamesh. The two heroes kill the bull and Enkidu flings one of its legs at Ishtar in contempt. For this affront to a deity, as well as his cruelty to Humbaba, the gods decree he must die.

Enkidu lingers in pain for some time, and when he dies, Gilgamesh falls into deep grief. Recognizing his own mortality through the death of his friend, he questions the meaning of life and the value of human accomplishment in the face of ultimate extinction. He cries:

How can I rest, how can I be at peace? Despair is in my heart. What my brother is now, that shall I be when I am dead. Because I am afraid of death I will go as best I can to find Utnapishtim whom they call the Faraway, for he has entered the assembly of the gods. (Book 9; Sandars, 97)

Casting away all of his old vanity and pride, Gilgamesh sets out on a quest to find the meaning of life and, finally, some way of defeating death. He travels far, through the mountains and past the Scorpion People, hoping to find Utnapishtim, the man who survived the Great Flood and was rewarded with immortality by the gods. At one point, he meets the tavern keeper Siduri who tells him his quest is in vain and he should accept life as it is and enjoy the pleasures it has to offer. Gilgamesh rejects her advice, however, as he believes life is meaningless if one must eventually lose all that one loves.

Siduri directs him to the ferryman Urshanabi, who takes him across the waters of death to the home of Utnapishtim and his wife. Utnapishtim tells him that there is nothing he can do for him. He was granted immortality by the gods, he says, and has no power to do the same for Gilgamesh. Even so, he offers the king two chances at eternal life. First, he must show himself worthy by staying awake for six days and nights, which he fails at, and then he is given a magic plant which, in a moment of carelessness, he leaves on the shore while he bathes, and it is eaten by a snake. Having failed in his quest, he has Urshanabi bring him back to Uruk, where he writes down his story on the city's walls.

Legacy & Continuing Debate

Through his struggle to find meaning in life, Gilgamesh defied death and, in doing so, becomes the first epic hero in world literature. The grief of Gilgamesh and the questions his friend's death evoke resonate with anyone who has struggled with grief and a meaning to life in the face of death. Although Gilgamesh ultimately fails to win immortality in the story, his deeds live on through his story – and so does he.

Since the tales informing The Epic of Gilgamesh existed in oral form long before it was written down, there has been much debate over whether the extant tale is more early Sumerian or later Babylonian in cultural influence. The best-preserved version of the story, as noted, comes from the Babylonian Shin-Leqi-Unninni, writing in Akkadian, drawing on original Sumerian source material. Regarding this, scholar Samuel Noah Kramer writes:

Of the various episodes comprising The Epic of Gilgamesh, several go back to Sumerian prototypes actually involving the hero Gilgamesh. Even in those episodes which lack Sumerian counterparts, most of the individual motifs reflect Sumerian mythic and epic sources. In no case, however, did the Babylonian poets slavishly copy the Sumerian material. They so modified its content and molded its form, in accordance with their own temper and heritage, that only the bare nucleus of the Sumerian original remains recognizable. As for the plot structure of the epic as a whole – the forceful and fateful episodic drama of the restless, adventurous hero and his inevitable disillusionment – it is definitely a Babylonian, rather than a Sumerian, development and achievement. (Sumer, 270)

As far as the meaning of the piece goes, however, it is actually irrelevant which civilization contributed more to its composition, as it is with any great work of literature. The Epic of Gilgamesh does not belong to any one civilization or time period, as far as its depiction of the human condition is concerned, any more than the Mahabharata, Iliad, Odyssey, Shahnameh, or Aeneid do. Obviously, a work of literature is influenced by the civilization that produced it, but the greatest works, like Gilgamesh, transcend such considerations.

Conclusion

In the present day, fascination with Gilgamesh continues as it has since the work was first translated in the 1870s. A German team of archaeologists, to cite only one example, claim to have discovered his tomb in April of 2003. Archaeological excavations, conducted through modern technology involving magnetization in and around the old riverbed of the Euphrates, have revealed garden enclosures, specific buildings, and structures described in The Epic of Gilgamesh, including Gilgamesh's tomb. According to The Death of Gilgamesh, he was buried at the bottom of the Euphrates when the waters parted after he died.

Whether the historical king existed is no longer relevant, however, as the character has taken on a life of his own over the centuries. At the end of the story, when Gilgamesh lies dying, the narrator says:

The heroes, the wise men, like the new moon have their waxing and waning. Men will say, "Who has ever ruled with might and with power like [Gilgamesh]?" As in the dark month, the month of shadows, so without him there is no light. O Gilgamesh, you were given the kingship, such was your destiny, everlasting life was not your destiny. Because of this, do not be sad at heart, do not be grieved or oppressed; he has given you power to bind and to loose, to be the darkness and the light of mankind. (Sanders, 118)

The story of Gilgamesh's failure to realize his dream of immortality is the very means by which he attains it. The epic itself is immortality and has served as the model for any similar tale which has been written since. It is far more than that, though, as Mitchell explains:

Part of the fascination of Gilgamesh is that, like any great work of literature, it has much to tell us about ourselves. In giving voice to grief and the fear of death, perhaps more powerfully than any book written after it, in portraying love and vulnerability and the quest for wisdom, it has become a personal testimony for millions of readers in dozens of languages.

But it also has a particular relevance in today's world, with its polarized fundamentalisms, each side fervently believing in its own righteousness, each on a crusade, or jihad, against what it perceives as an evil enemy. The hero of this epic is an antihero, a superman (superpower, one might say) who doesn't know the difference between strength and arrogance. By preemptively attacking a monster, he brings on himself a disaster that can only be overcome by an agonizing journey, a quest that results in wisdom by proving its own futility. The epic has an extraordinarily sophisticated moral intelligence. In its emphasis on balance and in its refusal to side with either hero or monster, it leads us to question our dangerous certainties about good and evil. (2)

Gilgamesh encourages hope in that, even though one may not be able to live forever, the choices one makes in life resonate in the lives of others. These others may be friends, family, acquaintances, or may be strangers living long after one's death who continue to be touched by the eternal story of the refusal to accept a life without meaning. Gilgamesh's struggle against apparent meaninglessness defines him – just as it defines anyone who has ever lived – and his quest continues to inspire those who recognize how intrinsically human that struggle is and always will be.