![Hannibal Barca [Artist's Impression] (by Creative Assembly, Copyright) Hannibal Barca [Artist's Impression] (by Creative Assembly, Copyright)](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/8476.jpg?v=1771333046)

Hannibal (also known as Hannibal Barca, l. 247-183 BCE) was a Carthaginian general during the Second Punic War between Carthage and Rome (218-202 BCE). He is considered one of the greatest generals of antiquity and his tactics are still studied and used in the present day. His father was Hamilcar Barca (l. 275-228 BCE), the great general of the First Punic War (264-241 BCE).

These wars were fought between the cities of Carthage in North Africa and Rome in northern Italy for supremacy in the Mediterranean region and the second war resulted directly from the first. Hannibal assumed command of the troops following his father's death and led them victoriously through a number of engagements until he stood almost at the gates of Rome; at which point he was stopped, not by the Romans, but through a lack of resources to take the city.

He was called back to Africa to defend Carthage from Roman invasion, was defeated at the Battle of Zama in 202 BCE by Scipio Africanus (l. 236-183 BCE) and retired from service to Carthage. The remainder of his life was spent as a statesman and then in voluntary exile at the courts of foreign kings. He died in 183 BCE by drinking poison.

Early Life

Although Hannibal is easily one of the most famous generals of antiquity, he remains a figure of some mystery. Scholar Philip Matyszak notes:

There is much we do not know about this man, though he was one of the greatest generals in antiquity. No surviving ancient biography makes him the subject, and Hannibal slips in and out of focus according to the emphasis that other authors give his deeds and character. (24)

Nothing is known of his mother and, although he was married at the time of some of his greatest victories, no records make mention of his wife other than her name, Imilce, and the fact that she bore him a son. What became her or her son is not known. The story of Hannibal's life is told largely by his enemies, the Romans, through the historians who wrote of the Punic Wars.

The Greek historian Polybius (l. c. 208-125 BCE) writes how Hannibal's father invited him to join an expedition to Spain when the boy was around nine years old. Hannibal eagerly accepted the invitation but, before he was allowed to join up, his father "took Hannibal by the hand and led him to the altar. There he commanded Hannibal to lay his hand on the body of the sacrificial victim and to swear that he would never be a friend to Rome" (3:11). Hannibal took the vow gladly - and never forgot it.

He accompanied his father to Spain and learned to fight, track and, most importantly, out-think an opponent. Matyszak comments how "the modern concept of teenagers as somewhere between child and adult did not exist in the ancient world, and Hannibal was given charge of troops at an early age" (23). When his father drowned, command of the army passed to Hasdrubal the Fair (l. c. 270-221 BCE), Hamilcar's son-in-law, and when Hasdrubal was assassinated in 221 BCE the troops unanimously called for the election of Hannibal as their commander even though he was only 25 years old at the time.

Crossing the Alps & Early Victories

Following the First Punic War the treaty between Carthage and Rome stipulated that Carthage could continue to occupy regions in Spain as long as they maintained the steady tribute they now owed to Rome and remained in certain areas. In 219 BCE the Romans orchestrated a coup in the city of of Saguntum which installed a government hostile to Carthage and her interests. Hannibal marched on the city in 218 BCE, lay siege to it, and took it. The Romans were outraged and demanded Carthage hand their general over to them; when Carthage refused, the Second Punic War was begun.

Hannibal decided to bring the fight to the Romans and invade northern Italy in 218 BCE by crossing the mountain range of the Alps. He left his brother Hasdrubal Barca (l. c. 244-207 BCE) in charge of the armies in Spain and set out with his men for Italy. On the way, recognizing the importance of winning the people to his side, he portrayed himself as a liberator freeing the people of Spain from Roman control.

His army grew steadily with new recruits until he had 50,000 infantry and 9,000 cavalry by the time he reached the Alps. He also had with him a number of elephants which he had found very useful in terrorizing the Roman army and their cavalry. Upon reaching the mountains he was forced to leave behind his siege engines and a number of other supplies he felt would slow their progress and then had the army begin their ascent.

The troops and their general had to battle not only the weather and the incline but hostile tribes who lived in the mountains. By the time they reached the other side, 17 days later, the army had been reduced to 26,000 men in total and a few elephants. Still, Hannibal was confident he would be victorious and led his men down onto the plains of Italy.

The Romans, meanwhile, had no idea of Hannibal's movements. They never considered he would move his army over the mountains to reach them and thought he was still in Spain somewhere. When word reached Rome of Hannibal's maneuver, however, they were quick to act and sent the general Scipio (father of Scipio Africanus the Elder, who accompanied him) to intercept. The two armies met at the Ticino River where the Romans were defeated and Scipio almost killed

Hannibal next defeated his enemies at Lake Trasimene and quickly took control of northern Italy. He had no siege machines and no elephants to take any of the cities and so relied on his image as liberator to try to coax the cities over to his side. He then sent word to Carthage for more men and supplies, especially siege engines, but his request was denied. The Carthaginian senate believed he could handle the situation without any added expense on their part and suggested his men live off the land.

Hannibal's Tricks & the Battle of Cannae

Hannibal's strategy of presenting himself as a liberator worked and a number of cities chose to side with him against Rome while his victories on the field continued to swell his ranks with new recruits. After the Battle of Trebbia (218 BCE), where he again defeated the Romans, he retreated for the winter to the north where he developed his plans for the spring campaign and developed various strategems to keep from being assassinated by spies in his camp or hired killers sent by the Romans. Polybius writes how Hannibal,

had a set of wigs made, each of which made him look like a man of a different age. He changed these constantly, each time changing his apparel to match his appearance. Thus he was hard to recognize, not just by those who saw him briefly, but even by those who knew him well. (3:78)

Once spring came, Hannibal launched a new assault, destroying the Roman army under Gaius Flaminius and another under Servilius Geminus.

The Romans then sent the general Quintus Fabius Maximus (l. c. 280-203 BCE) against Hannibal who employed a new tactic of wearing Hannibal down by keeping him constantly on the move and off balance. Fabius became known as "the delayer" by refusing to face Hannibal directly and delaying any face-to-face engagement; he preferred instead to strategically place his armies to prevent Hannibal from either attacking or retreating from Italy. So successful was Fabius' strategy that he almost caught Hannibal in a trap.

He had the Carthaginians penned up near Capua where retreat was blocked by the Volturnus River. It seemed that Hannibal had to either fight his way out or surrender but then, one night, the Romans saw a line of torches moving from the Carthaginian camp emplacement toward an area they knew was held by a strong garrison of their own.

It seemed clear Hannibal was trying to break out of the trap. Fabius' generals encouraged him to mount a night attack to support the garrison and crush the enemy between them but Fabius refused, believing that the garrison in place could easily prevent Hannibal from breaking out and would hold until morning. When the garrison mobilized to march out and meet Hannibal in battle, however, they found only cattle with torches tied on their horns and Hannibal's army had slipped away through the pass the Romans had left untended.

Fabius' tactic of refusing to meet Hannibal in open battle was beginning to wear on the Romans who demanded direct action. They appointed a younger general, Minucius Rufus (dates unknown), as co-commander as Rufus was confident he could defeat Hannibal and bring peace back to the region. Fabius understood that Hannibal was no common adversary, however, and still refused to engage. He gave Rufus half the army and invited him to do his best. Rufus attacked Hannibal near the town of Gerione and was so badly defeated that Fabius had to save him and what was left of his troops from complete annihilation. Afterwards, Fabius resigned his position and Rufus disappears from history.

Hannibal then marched to the Roman supply depot of Cannae, which he took easily, and then gave his men time to rest. The Romans sent the two consuls Lucius Aemilius Paulus (d. 216 BCE) and Caius Terentius Varro (served c. 218-200 BCE), with a force of over 80,000, against his position; Hannibal had less than 50,000 men under his command. As always, Hannibal spent time learning about his enemy, their strengths and weaknesses, and knew that Varro was eager for a fight and over-confident of success. As the two consuls traded off command of the army, it worked to Hannibal's advantage that the more ambitious and reckless of the two, Varro, held supreme authority on the first day of battle.

Hannibal arranged his army in a crescent, placing his light infantry of Gauls at the front and center with the heavy infantry behind them and light and heavy cavalry on the wings. The Romans under Varro's command were placed in traditional formation to march toward the center of the enemy's lines and break them. Varro believed he was facing an opponent like any of the others Roman legions had defeated in the past and was confident that the strength of the Roman force would break the Carthaginian line; this was precisely the conclusion Hannibal hoped he would reach.

When the Roman army advanced, the center of the Carthaginian line began to give way so that it seemed as though Varro had been correct and the center would break. The Carthaginian forces fell back evenly, drawing the Romans further and further into their lines, and then the light infantry moved to either end of the crescent formation and the heavy infantry advanced to the front. At this same time, the Carthaginian cavalry engaged the Roman cavalry and dispersed them, falling on the rear on the Roman infantry.

The Romans, continuing in their traditional formation with their well-rehearsed tactics, continued to press forward but now they were only pushing those in the front lines into the killing machine of the Carthaginian heavy infantry. The Carthaginian cavalry had now closed the gap behind and the forces of Rome were completely surrounded. Of the 80,000 Roman soldiers who took the field that day, 44,000 were killed while Hannibal lost around 6,000 men. It was a devastating defeat for Rome which resulted in a number of the Italian city-states defecting to Hannibal and Philip V of Macedon (r. 221-179 BCE) declaring in favor of Hannibal and initiating the First Macedonian War with Rome.

The people of Rome mobilized to defend their city, which they were sure Hannibal would move on next. Veterans and new recruits alike refused pay in order to defend the city. Hannibal, however, could make no move on Rome because he lacked siege engines and reinforcements for his army. His request for these necessary supplies was refused by Carthage because the senate did not want to exert the effort or spend the money.

Hannibal's commander of the cavalry, Maharbal, encouraged Hannibal to attack anyway, confident they could win the war at this point when the Roman army was in disarray and the people in a panic. When Hannibal refused, Maharbal said, "You know how to win a victory, Hannibal, but you do not know how to use it." Hannibal was right, however; his troops were exhausted after Cannae and he had neither elephants nor siege engines to take the city. He did not even have enough men to reduce the city by encircling it for a long siege. If Carthage had sent the requested men and supplies at this point, history would have been written very differently; but they did not.

Further Campaigns & The Battle of Zama

Among the Roman warriors who survived Cannae was the man who would come to be known as Scipio Africanus the Elder. Scipio's father and uncle, two of the former commanders, had been killed fighting Hasdrubal Barca in Spain and, when the Roman senate called for a general to defend the city against Hannibal, all of the most likely commanders refused believing, after Cannae, that any such command was simply a suicide mission. Scipio, only 24 years old at the time, volunteered. He left Rome with only 10,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry to meet Hannibal's much larger force.

Scipio began in Spain - not Italy - in an effort to subdue Hasdrubal first and prevent reinforcements from reaching Italy. He first took the city Carthago Nova and moved on from there to other victories. In 208 BCE, he defeated Hasdrubal at the Battle of Baecula using the same tactic Hannibal had at Cannae.

Hasdrubal, recognizing that Spain was a lost cause, crossed the Alps to join Hannibal in Italy for a united attack on Rome. At the Battle of the Metaurus River in 207 BCE, however, Hasdrubal's army was defeated by the Romans under Gaius Claudius Nero (c. 237-199 BCE); Hasdrubal was killed and his forces scattered. Nero had been engaging Hannibal in the south but slipped away in the night, defeated Hasdrubal, and returned without Hannibal ever noticing. The first Hannibal knew of Hasdrubal's defeat was when a Roman contingent threw his brother's head to the sentries of his camp.

Scipio, still in Spain, requested money and supplies from the Roman senate to take the fight to Hannibal by attacking Carthage; a move which, he was sure, would force Carthage to recall Hannibal from Italy to defend the city. The Roman senate refused and so Scipio shamed them by raising his own army and appealing to the people of Rome for support; the senate then relented and gave him command of Sicily from which to launch his invasion of North Africa.

Hannibal, in the meantime, was forced to continue his previous strategy of striking at Rome in quickly orchestrated engagements, and trying to win city-states to his cause, without being able to take any city by storm. Matyszak writes:

In the field, Hannibal remained umatched. In 212 and 210 he took on the Romans and defeated them. But he now understood that the wound Rome had received at Cannae had not been mortal. The flow of defections to the Carthaginian side slowed and then stopped. (39)

In Spain, the Carthaginians had been defeated by Scipio but Hannibal had no knowledge of this; he only knew his brother had been killed but not that Spain was under Roman control.

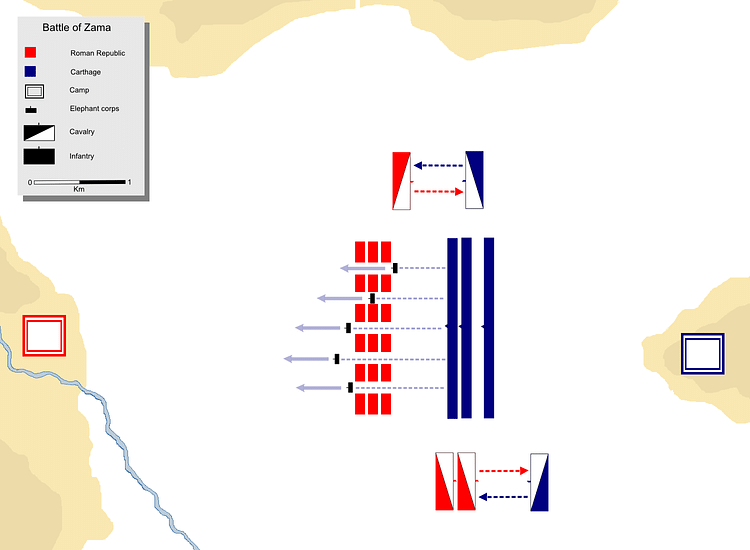

By this time, Scipio was already set to invade North Africa and his plan would work exactly as he predicted. In 205 BCE he landed his forces and allied himself with the Numidian King Masinissa. He quickly took the Carthaginian city of Utica and marched on toward Carthage. Hannibal was recalled from Italy to meet this threat and the two forces met on the field in 202 BCE at the Battle of Zama.

Scipio had studied Hannibal's tactics carefully in the same way that Hannibal had always taken pains to know his enemy and out-think his opponents. He had no experience in facing Scipio, however, and only knew him as the young general who had somehow managed to defeat Hasdrubal in Spain. Scipio seemed to conform to Hannibal's expectations when he arranged his forces in traditional formation in a seemingly tight cluster.

Hannibal was certain he would scatter these Romans easily with an elephant charge but Scipio used his front line as a screen for a very different kind of formation: instead of the closely-packed configuration presenting a horizontal front across the line (the formation Hannibal saw from his position) he arranged his troops in vertical rows behind the front line. When Hannibal launched his elephant charge, Scipio's front line simply moved aside and the elephants ran harmlessly down the alleys between the Roman troops who then killed their handlers and turned the elephants around to crush the ranks of the Carthaginians; Hannibal was defeated and the Second Punic War was over.

Later Years & Legacy

After the war, Hannibal accepted a position as Chief Magistrate of Carthage at which he performed as well as he had as a military leader. The heavy fines imposed on defeated Carthage by Rome, intended to cripple the city, were easily paid owing to the reforms Hannibal initiated. The members of the senate, who had refused to send him aid when he needed it in Italy, accused him of betraying the interests of the state by not taking Rome when he had the chance but, still, Hannibal remained true to the interests of his people until the senators trumped up further charges and denounced Hannibal to Rome claiming he was making Carthage a power again so as to challenge the Romans. Exactly why they decided to do this is unclear except for their disappointment in him following defeat at Zama and simple jealousy over his abilitites.

In Rome, Scipio was also dealing with problems posed by his own senate as they accused him of sympathizing with Hannibal by pardoning and releasing him, accepting bribes, and misappropiating funds. Scipio defended Hannibal as an honorable man and kept the Romans from sending a delegation demanding his arrest but Hannibal understood it was only a matter of time before his own countrymen turned him over and so he fled the city in 195 BCE for Tyre and then moved on to Asia Minor where he was given the position of consultant to Antiochus III (the Great, r. 223-187 BCE) of the Seleucid Empire.

Antiochus, of course, knew of Hannibal's reputation and did not want to risk placing so powerful and popular a man in control of his armies and so kept him at court until necessity drove him to appoint Hannibal admiral of the navy in a war against Rhodes, one of Rome's allies. Hannibal was an inexperienced sailor, as was his crew, and was defeated even though, much to his credit, he came close to winning. When Antiochus was defeated by the Romans at Magnesia in 189 BCE, Hannibal knew that he would be surrendered to Rome as part of the terms and again took flight.

At the court of King Prusias of Bithynia in 183 BCE, with Rome still in pursuit, Hannibal chose to end his life rather than be taken by his enemies. He said, "Let us put an end to this life, which has caused so much dread to the Romans" and then drank poison. He was 65 years old. During this same time, in Rome, the charges against Scipio had disgusted him so much that he retreated to his estate outside the city and left orders in his will that he be buried there instead of in Rome. He died the same year as Hannibal at the age of 53.

Hannibal became a legend in his own lifetime and, years after his death, Roman mothers would continue to frighten their unwilling children to bed with the phrase "Hannibal ad Porto" (Hannibal is at the door). His campaign across the Alps, unthinkable even in his day, won him the grudging admiration of his enemies and enduring fame ever since.

Hannibal's strategies, learned so well by Scipio, were incorporated into Roman tactics and Rome would consistently use them to good effect following the Battle of Zama. After the deaths of Hannibal and Scipio, Carthage continued to cause problems for Rome which eventually resulted in the Third Punic War (149-146 BCE) in which Carthage was destroyed.

The historian Ernle Bradford writes that Hannibal's war against the Romans,

may be regarded as the last effort of the old eastern and Semitic peoples to prevent the domination of the Mediterranean world by a European state. That it failed was due to the immense resilience of the Romans, both in their political constitution and in their soldiery. (210)

While there is some truth to this, Hannibal's ultimate defeat was brought about by his own people's weakness for luxury, wealth, and ease as much as by the Roman refusal to surrender after Cannae. There is no doubt, as Bradford also notes, that had Hannibal "been fighting against any other nation in the ancient world...his overwhelming victories would have brought them to their knees and to an early capitulation" (210) but the cause of Hannibal's defeat was just as much the fault of the Carthaginian elite who refused to support the general and his troops who were fighting for their cause.

No records exist of Carthage awarding Hannibal any recognition for his service in Italy and he was honored more by Scipio's pardon and defense than by any actions on the part of his countrymen. Even so, he continued to do his best for his people throughout his life and remained true to the vow he had taken when young; to the end, he remained an enemy of Rome and his name would be remembered as Rome's greatest adversary for generations - and even to the present day.