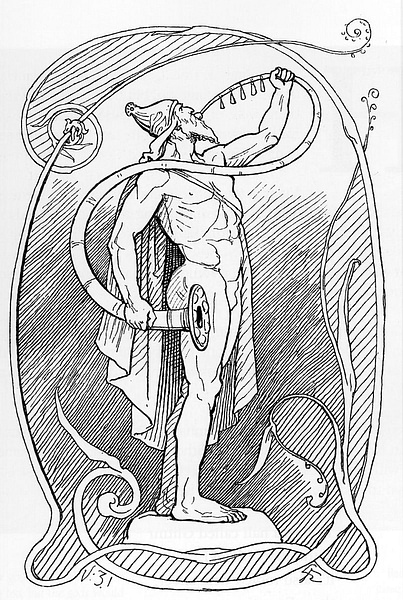

Heimdall is a mysterious deity of Norse mythology whose main attribute refers to guarding the realm of the gods, Asgard, from his high fortress called Himinbjörg found at the top of Bifröst, the rainbow bridge. He has the might of sea and earth, very keen eyesight, always on the lookout for danger, and when intruders are approaching, he sounds his Gjallarhorn, the resounding horn. This horn will announce the beginning of Ragnarök, the apocalypse that will have Heimdall battling Loki, one of the leaders of giants. Furthermore, some fragments of Norse poetry describe Heimdall as the father of all mankind.

Sources

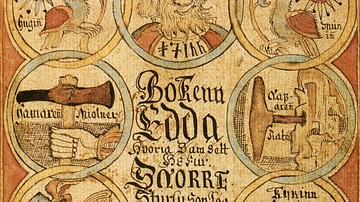

According to Snorri Sturluson, the 13th-century Icelandic scholar and author of the mythological textbook The Prose Edda, Heimdall belongs to the Æsir family as a son of Odin and is known as the white god, whiteness in Old Norse being linked to beauty and uprightness. He has a horse named Gulltopp and a horn called Gjallar. He needs less sleep than a bird, he can see at an extraordinary distance, he can hear the grass and the wool on sheep grow. He is also called Gullintanni ("golden-toothed") and Hallinskidi ("the one with sided horns" – indicating an unclear link to rams).

Snorri also quotes a poem called Heimdalargaldr, which probably states one of the most curious details about Heimdall, that he is the offspring of nine mothers, nine sisters (Snorri, 26). This detail is corroborated with several lines in the poem Völuspá in skamma, or the short Völuspá, actually, a few stanzas surviving within another poem, the Hyndluljoth (Old Norse: Hyndluljóð), and one stanza quoted by Snorri. Originally found in a large compilation called Flateyjarbók, Hyndluljoth was later included in the Poetic Edda, the collection of mythological poems written in the 13th century in Iceland but circulating back in the 900s.

In the poem, the woman Hyndla traces some genealogies of heroes from the sagas. The inserted short Völuspá seems a tad confused and rushed, and its informative value is low. We should mention though that Heimdall’s giant mothers are mentioned here by name, which can be rendered Griper, Yelper, Foamer, Sand-Strewer, She-Wolf, Dusk, Fury, Sorrow-Flood, and Iron-Sword. We can only speculate about Heimdall’s birth, perhaps these mothers created his various parts or more abstract energies. Or given his mothers’ names, maybe he is born out of sea waves, the daughters of the sea god Aegir. Another question would be whether his mothers could be somehow connected to the nine worlds recalled by the seeress questioned by Odin in the first poem of The Poetic Edda, Völuspá (the prophecy of the wise woman) at the beginning of time (Hildebrand, 13).

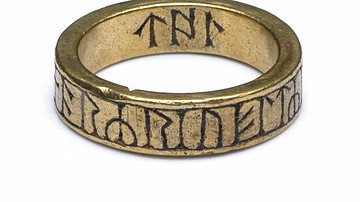

Another scrap of information about Heimdall we get from the same source in stanza 27 where the prophetess says she knows about the god’s horn (hljōþ) and that it is hidden under the holy tree, Yggdrasil. On it there pours a stream apparently coming from Odin’s eye, the one he sacrificed to get wisdom from the spirit Mimir. So is the horn buried there until Heimdall announces Ragnarök? Or would it rather refer to the sense of hearing and not an object? Maybe Heimdall placed his ear there as Odin did with his eye, which implies a connection to the World Tree, in other words with the cosmic order.

Speaking of Ragnarök, Snorri talks about the enmity between Heimdall and Loki who will face each other in this great event, but there were probably more stories involving these two characters that are now lost. The poem Húsdrápa, quoted in The Prose Edda, implies that these two once fought in the form of seals over Brisingamen, the goddess Freyja’s necklace. Moreover, the poem Lokasenna where Loki insults all the gods also refers to their hostility. In stanza 48, Loki silences Heimdall after he tells him off for being mad and drunk by saying that he must face the evil fate of having a stiff back all the time. This insult could be interpreted as Heimdall’s function as the watchman of the gods so he cannot move around freely.

One more scrap of myth comes up in the poem Thrymskvitha (Old Norse Þrymskviða), dealing with the disappearance of Thor’s hammer, where Heimdall makes an appearance in stanza 14 as "the whitest of gods", meaning the most handsome. In his wisdom, he suggests to Thor to get dressed up with the bridal veil to trick the giant who hid his weapon. The same fragment adds another interesting detail, that he can foretell the future like the Vanir, the other godly family in the Nordic pantheon broadly symbolizing prosperity, however, the term Vanir might simply be used to rhyme in the stanza.

Last but not least, in the chapter Skálskaparmál of the Prose Edda, where Snorri teaches poets to use metaphors (kenningar), he says that a sword can be referred to as Heimdall’s head because he was struck with a man’s head. This story has been lost. In the same source, he is identified as a son of Odin.

Heimdall the Creator

The main literary source for Heimdall’s role in Norse mythology as a forefather would be the poem Rigsthula (Old Norse: Rígsþula). The poem now belongs to the Poetic Edda, however, it is not found in the main manuscripts preserving it. Instead, it has been kept on the last page of a manuscript of the Prose Edda, Snorri Sturluson’s version of Norse myth. The manuscript called Codex Wormianus is, unfortunately, missing the end of the poem. Generally speaking, the poem deals with explaining the origins of the three main categories of Nordic society – serfs, commoners, and noblemen, with the last group providing the one who would become the future king. Iceland did not have kings and so the poem was most likely written on the continent, likely even for a particular king, but the manuscript breaks at the point where it could have made the connection between the mythical king and a real one.

The use of the name Rig ('king' in Old Irish) and some other words of Celtic origin reflect the frequent contacts between Norsemen and inhabitants from the Western Isles like the Orkneys. Perhaps the poet had been wandering for a while in Celtic-influenced territories and then composed his work for a Danish or Norwegian king. The person who added the introductory prose passage to the poem in the 13th or 14th century identified Rig with the god Heimdall, although this idea seems very doubtful. This Rig who is the forefather of mankind, described as old and wise, mighty and strong reminds us more of Odin than anyone else. It also reminds us of the fact that Norse mythology is much more twisted and messy than we like to believe. Besides this introduction, there is nothing in the poem confirming the equivalence of Rig and Heimdall. Nevertheless, there are a couple of vague references in other poems: in Völuspá in skamma / Hyndluljoth stanza 40 he is called "the kinsman of men" and stanza 13 of Grímnismál might imply that Heimdall "rules over men". Völuspá, the creation poem and prophecy about the end of the world, refers to the classes of men as "greater and lesser children of Heimdall" in the very first stanza (Hildebrand, 12).

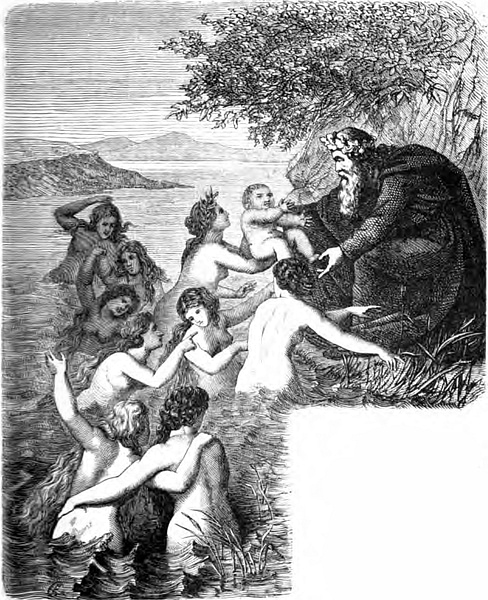

First Rig reaches the dwelling of Ai and Edda, great-grandfather and great-grandmother. On his visit Rig receives heavy and thick bread with calf broth, indicative of the low status of the family. The god then sleeps between them three nights long and nine months later Edda bears a son named Thrall (slave) whom they sprinkle with water, a habit apparently present in pre-Christian religion as well. Thrall has wrinkled skin, an ugly face, and a twisted back, and wrapped in a filthy cloth, "he made rope and carried baskets, all day long he carried firewood home" - (Hildebrand, 281). One day Thrall/Slave meets a woman called Thrir/Slave woman, with crooked legs, a flat nose, and sunburned arms. They beget children, whose names reflect their low social status: Lumpy, Barn-cleaner, Stinker, Horse-fly, etc. They mainly take care of pigs, grow crops, and shovel manure.

After creating the race of thralls, Rig/Heimdall moves on and comes across the next couple, Afi and Ama, grandfather and grandmother. This couple has a tidier appearance indicating their higher status. The man has a trimmed beard and fitting clothes, while his wife is wearing a headdress with brooches and a necklace. Their activities, carving and weaving, also seem more elevated. The same thing happens; Rig sleeps between them, and nine months later Karl (yeoman, freeman) is born. As he grows up, Karl "tames oxen, prepares plows, builds houses and barns, makes carts, and takes care of the plow" (Hildebrand, 287). Karl then exchanges rings with his future wife, Snör (daughter-in-law), dressed in goatskins and carrying the keys of the household. Their children bear revealing names for their status as well, such as Strong, Keeper of Lands, Craftsman, Dwelling-Owner, Farm-Keeper for men, and Worthy, Proud, Graceful, Fair for women.

Rig finally arrives at the third hall, with a wide portal and fresh straw on the floor, as if in preparation for a feast. Fathir, obviously father, is fashioning bows, as archery represents a high-status activity. The appearance of the lady of the house, Mothir, mother, enforces the image of elevated rank; a dress of quality cloth, a nice cap, a blue gown, clasps, bright brows, beautiful breasts, and most importantly, a white neck, a sign of nobility because it meant avoiding work outside and getting sunburnt. When they sit down to eat, she covers the board with embroidered cloth and brings thin loaves, well-cooked meat in silver vessels, and precious cups of wine. The pair’s son, born after Rig lays between them, is named Jarl (nobleman), wrapped in silk.

As the blonde and bright boy with grim eyes like a snake grows, he engages in hunting, archery, and riding. Rig/Heimdall comes to him because he has the essential knowledge to share with his chosen one: "Rig came striding / he taught him runes / he gave him his name / called him his son / asked him to claim lands / to claim old villages" (Hildebrand, 293). Jarl follows his master’s teachings and goes to war, reddening the fields and killing many. He amasses great wealth and offers arm rings to his followers to ensure loyalties. His messengers reach the hall of Hersir, a generic name referring to a local chieftain, the highest recognized authority before the establishment of the kingdom of Norway, to make a marriage proposal to his daughter Erna (“the Capable”). They get married and their children are named very vaguely Boy, Offspring, Descendant, or Heir. They play chess, swim, tame beasts and shake spears, but the wittiest seems to be Konr ungr, Kon the Young, which contracted is konungr, king. He learns to use the runes, understand the speech of birds, how to quench fires and calm sorrows, and soon becomes even craftier than Rig, gaining the right to take his name.

The poem ends abruptly with a crow urging Konr ungr to stop shooting arrows at birds and better battle other men, like the two rich chieftains living nearby. Their given names, Dan and Danp, might suggest a connection with the Danes.

Hypothetical Meanings

Lindow makes an interesting remark about Heimdall’s place in Norse mythology:

[Heimdall] seems to have a certain connection with peripheral locations: born at the edge of the earth, encountering humans by a coast, stationed at the end of heaven to guard against giants. These places are all to some extent boundaries: between land and sea, between the world of the gods and that of the giants. Being born in days of yore also situates Heimdall at a temporal periphery. Heimdall’s other main action in the mythology involves not a spatial but a temporal boundary, namely, his sounding of the Gjallarhorn at the outset of Ragnarök. (Lindow 2002, 171).

Heimdall and humanity begin their existence somewhere at the edge. At the same time, due to his role as a watchman, we could assume Heimdall may have been thought of as some kind of guardian spirit of the household. Heimdall seems to be important in literary sources, at least hinted at in what has survived, but his obscure name does not seem to have been preserved in place names, unlike that of other obscure gods. Heim means 'world', but dall remains unclear (not to be confused with dalr – valley), although Jan de Vries’ explanation - a type of fruitful tree, in this case solidifying the bond between the god, nature, and mankind - could work. The Poetic Edda tells us that the first humans were pieces of wood, then Heimdall comes and continues the act of creation. If we accept this etymology, his name would be synonymous with Yggdrasil, the ash tree keeping the universe together. The idea of a tree-figure, a pillar watching over us is quite common in circumpolar myths as well and so some have proposed Finnic influence.

Parallels to other gods are hard to draw, but we can look at some vague similarities with Mannus, the primal being fathering the three main Germanic tribes mentioned by Tacitus (c. 56 - c. 118 CE); Agni the fire god of Vedic mythology who also begets human descendants; civilizing heroes like the Greek Prometheus or Finnish Väinämöinen; and the White Youth fathering the human race in Yakut legends. Davidson also points to Irish traditions about a god of the sea, Manannán, going from house to house. Heimdall has the might of earth and sea, as told in the shorter Völuspá. His links with Asgard, the World Tree, mankind, the sea, the beginning, and the end make him a complex and intriguing god. Besides the literary sources, a 10th-century cross in Cumbria, England, depicts on one of the panels a character with a horn; most likely the cross draws parallels between Norse and Christian myths. The inconclusive case of Heimdall reminds us that the incoherent stories and contradictory aspects of mythological figures were just an expression of the big diversity of beliefs.